On the Prow of Liberty

By Kathryn MilesEleven months before the attack on Pearl Harbor forced the United States to enter World War II, President Roosevelt announced a bold plan to build two hundred new merchant ships that would supply Great Britain and the war effort.

These were the first of the Liberty Ships, credited with turning the tide of the war and advancing the Allies to victory. In foot-tall letters across the bow of forty-three of these famous vessels were names that are familiar—alumni, board members, and other illustrious members of the Bowdoin community.

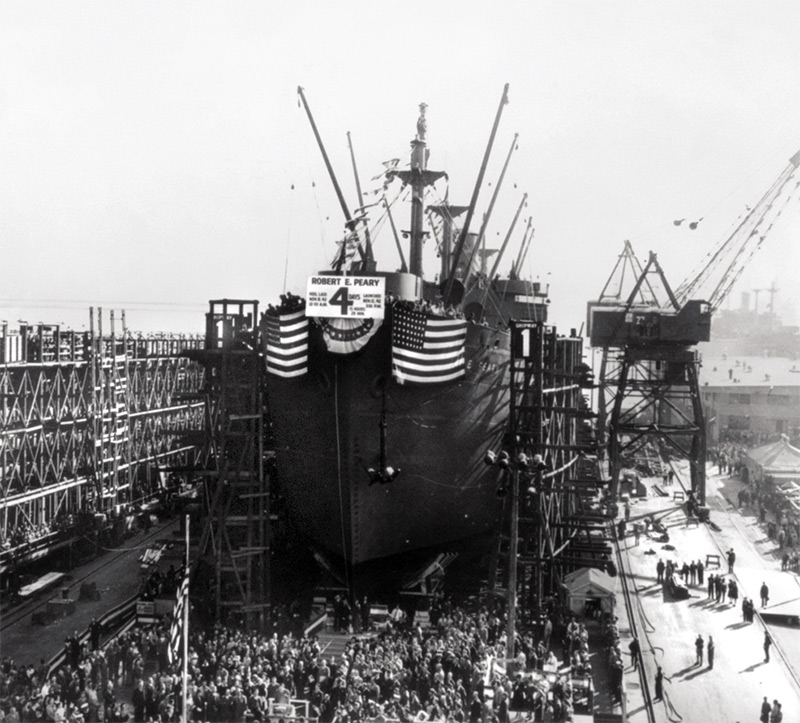

The SS Joseph N. Teal ready to launch on September 13, 1942. The Oregon Shipbuilding Corporation set a record, building the Teal in just ten days, a feat bested by almost six days by Kaiser shipyards with the Peary two months later.

IN OCTOBER 1940, the world was at war. Poland and much of Scandinavia had fallen to Germany. France and England were both under siege as well. Having faced catastrophic naval losses at the hands of the Nazis, Britain feared a total collapse. As a last-ditch effort, a delegation of British shipbuilders, surveyors, and members of the admiralty arrived in the US with one desperate mission: to find a shipyard capable of building sixty merchant vessels that could continue the Allies’ fight. It would not be an easy battle. The empire’s commercial fleet had sustained catastrophic losses during World War I; the global Great Depression had stymied that fleet’s recovery. Now, just a year into the second World War, Britain was facing immeasurable odds. Squadrons of German U-boat submarines known as “wolf packs” were laying siege on the almost entirely unprotected merchant fleet and threatened to collapse the empire’s economy, leaving millions of people without basic goods and supplies.

Once in the US, the British shipbuilding delegation—known colloquially as “the Mission”—met with high-ranking members of the US Maritime Commission and received permission to contract with boatyards here. They chartered a commercial plane and spent three weeks barnstorming the continent, searching for a company capable of building the 7,463-ton ships.

In the end, they found three: The Henry J. Kaiser Company, a steel and paving company that had recently completed work on the Hoover and Grand Coulee Dams; New York-based Todd Shipyards; and Maine’s Bath Iron Works (BIW), which was founded in 1884 by Bowdoin alumnus Thomas Hyde, Class of 1861. Todd and BIW already had extensive experience building large ships; Kaiser, while not a shipbuilder, brought revolutionary techniques in welding and prefabricated metals. Collectively, they established two new yards: the Todd-California Shipbuilding Corporation, in Richmond, California, and Todd-Bath Iron Shipbuilding Corporation, located in South Portland, Maine.

Each of these two yards was responsible for building thirty of the British merchant ships. Construction began in December 1940. By then, the United States had come to understand its own merchant vessel crisis. Most of the American ships had been built in the years leading up to World War I. By 1940, they were antiquated and in bad repair. And while the US had managed to stay out of the war to that point, the country was facing increased shipping demands as a result of fighting overseas, which was proving all too starkly the insufficiencies of the US merchant fleet.

On January 3, 1941, President Franklin D. Roosevelt announced a $350 million plan to build two hundred new merchant ships based on the design of the sixty British vessels. Officially designated as part of the emergency cargo class, they were given the more popular moniker of Liberty Ships, a nod to Patrick Henry’s fiery speech on the eve of the Revolutionary War.

Like their British counterparts, Liberty Ships would be built based on Kaiser’s innovations in prefabrication: subassemblies would be constructed at factories around the country and then shipped by rail to yards like Todd-Bath Iron.

“It was the realization of a concept shipbuilders had been dreaming about for decades,” said Josh Smith, associate professor of history at the US Merchant Marine Academy and director of the American Merchant Marine Museum. “This idea of building components in separate facilities and bringing them together to assemble quickly really was revolutionary.”

Nevertheless, President Roosevelt was famously no fan of their design. He called them “dreadful looking objects.” Time magazine agreed, dubbing them “ugly ducklings.” But what the vessels may have lacked in aesthetics they more than compensated for in functionality. Their design included five cargo holds capable of carrying 7,800 tons of supplies—the equivalent of about a mile and a half of railroad boxcars. They were propelled by 2,500-horsepower steam engines and armed with both antiaircraft and submarine fighting guns.

Welder-trainee Josie Lucille Owens works on the Liberty Ship SS George Washington Carver at the Kaiser shipyards in Richmond, California, in 1943.

“Liberty Ships weren’t about being the best or the most modern,” said Smith. “It was about reducing construction and design to their most simple forms, so that they could be replicated again and again, and by workers without previous shipbuilding experience.”

Instead of using more traditional riveted fastenings, Liberty Ship components were welded together, which made the ships less time-consuming to complete, said Smith. Welding, he added, was also much easier to teach to workers new to the trade; it also required less upper body strength, which meant that a greater cross section of workers—including women—could undertake it.

Approximately 1.8 million Americans were employed in Liberty shipyards during the war. Yard owners touted equal hiring practices. Some payrolls comprised as many as 50 percent Black workers and 10 percent women. Henry Kaiser provided childcare and health insurance for his employees (indeed, the contemporary health care consortium Kaiser Permanente would grow out of these practices). But, said Smith, working conditions were far from egalitarian in most yards. Women and minority workers were often relegated to the most menial of jobs and rarely received the same wages as their white male counterparts. Race riots at Southern yards were often prompted by white workers, and in some cases led to the murder of Black yard workers.

“It definitely wasn’t always the idealized Rosie the Riveter image,” said Smith. “And many women and minority employees were let go after the war. But these yards at least paved the way for more equality in the workplace nationwide.”

LIBERTY SHIPS WERE PRIZED for their versatility, but it was the speed at which they were constructed that made them revolutionary. Each ship in the first generation of Liberty Ships took more than two hundred days to complete. By 1942, when the US was firmly entrenched in the war, workers had reduced that time to about seventy days per ship and were launching, on average, about three each day—a Herculean feat by any standard.

At that same time, South Portland, Maine, had become a hub for Liberty Ship construction. Todd-Bath Iron, having finished with the British contract, began work on American ships as well. It was soon joined by the New England Shipbuilding Corporation. Known to locals as the East and West Yards, respectively, this conglomeration of yards appeared from Casco Bay a veritable monolith of cranes, sliding ways, and watertight basins. Towers of scaffolding enveloped ships, and a Byzantine collection of warehouses and outbuildings filled the area surrounding what is now Bug Light Park, said Kathryn DiPhilippo, executive director and curator for the South Portland Historical Society.

“Over 30,000 workers here were employed in twenty-four-hour construction every day of the week,” said DiPhilippo. “It was never not busy.”

Fifteen additional shipyards across the United States and Canada operated at a similar rate. As workers increased the speed at which they completed the vessels, the US Maritime Commission struggled to name individual ships. How particular names were chosen has been largely lost to history, but DiPhilippo thinks that individual yards may have maintained suggestions from employees and local elected officials, which were then forwarded to the national office.

Writers were a popular choice for ship monikers, and several chosen names had strong Bowdoin ties, including Harriet Beecher Stowe, Nathaniel Hawthorne (Class of 1825), and Henry Wadsworth Longfellow (Class of 1825). Other luminaries with Bowdoin connections, such as James Bowdoin, Joshua Chamberlain (Class of 1852), and William DeWitt Hyde, the College’s seventh president, were also chosen.

Launches of new vessels occurred so regularly that they often passed without much fanfare, said DiPhilippo. But there were exceptions. When the SS William DeWitt Hyde was launched on August 31, 1943, it was christened in a formal ceremony by Edith Lansing Sills, wife of then-president of the College Kenneth C. M. Sills. The couple was joined by a delegation of “some fifty Bowdoin men who are yard employees, together with their wives,” wrote the Lewiston Daily Sun, which covered the event.

No amount of fanfare in South Portland could rival that received by the launching of the SS Robert E. Peary, however.

Bowdoin Connections

Of the 2,710 Liberty Ships built during World War II, forty-three were named after people with Bowdoin connections, including alumni, honorary degree recipients, overseers, and trustees. Here are some of them.

James G. Blaine H’1884

Overseer, 1866–1873. Represented Maine in the US House of Representatives, served as Speaker of the House of Representatives, was a US senator, and served twice as US secretary of state.

James Bowdoin

College namesake. Second governor of Massachusetts. One of many cofounders, including John Adams and John Hancock, of the American Academy of Arts and Sciences.

Joshua L. Chamberlain, Class of 1852, H’1869

President of the College, 1871–1883. Trustee, 1867–1914. Left his professorship to lead the 20th Maine Volunteer Infantry Regiment, received the Congressional Medal of Honor for the defense of Little Round Top at Gettysburg, and accepted the surrender of the Confederate troops at Appomattox. Governor of Maine from 1867 to 1871.

Henry Dearborn

Overseer, 1794–1798. Served under Benedict Arnold in the expedition to Québec (of which his journal is an important historical record). He was US secretary of war under President Jefferson and a general in the War of 1812.

William Pitt Fessenden, Class of 1823, H’1858

Overseer, 1843–1860. Trustee, 1860–1869. Maine legislator, member of the US House of Representatives, US senator from Maine, and Abraham Lincoln’s secretary of the treasury from 1864 to 1865.

Nathaniel Hawthorne, Class of 1825

Author of The Scarlet Letter and The House of the Seven Gables, among others. Appointed US consul in Liverpool, England, by President Franklin Pierce (Class of 1824).

William DeWitt Hyde H’1886, H’1917

President of the College, 1885–1917. Served as a minister prior to his post as Bowdoin president and professor of mental and moral philosophy. As president, he enlarged the faculty, revolutionized the curriculum, and oversaw several defining construction projects.

Thomas W. Hyde, Class of 1861

Civil War brigadier general from Bath, Maine, and Congressional Medal of Honor recipient for his role at the Battle of Antietam. A three-term Maine state senator and two-time mayor of Bath, he was founder and president of Bath Iron Works.

Sumner I. Kimball, Class of 1855, H’1891

In charge of the Revenue Marine Bureau in the US Department of the Treasury, he founded the United States Life-Saving Service, a precursor to the US Coast Guard, and served as its superintendent for thirty-seven years.

Henry W. Longfellow, Class of 1825, H’1874

Bowdoin professor of modern languages and librarian of the College from 1829 to 1835. One of the most well-known poets of all time, he is remembered for such poems as “The Song of Hiawatha,” “Paul Revere’s Ride,” and “The Courtship of Miles Standish.”

Robert E. Peary, Class of 1877, H’1894, H’1910

Served in the United States Coast and Geodetic Survey and the United States Navy, rising to the rank of rear admiral. Best known as the Arctic explorer who discovered the North Pole in 1909.

Thomas B. Reed, Class of 1860, H’1890

Served in the Maine House of Representatives and Maine Senate, as Maine Attorney General, as US Representative for Maine’s First Congressional District, and as US Speaker of the House.

Harriet Beecher Stowe

The famous abolitionist and author came to Brunswick in 1850 with her husband, Bowdoin alumnus and religion professor Calvin Stowe (Class of 1824). She wrote much of Uncle Tom’s Cabin in Calvin’s Appleton Hall office and at their home at 63 Federal Street.

The SS Robert E. Peary ready to launch at Kaiser Shipyards in Richmond, California, on November 12, 1942. The Peary became famous for being assembled in a record four days, fifteen hours, and twenty-nine minutes, a promotional endeavor to showcase innovation and boost wartime morale.

Peary, who graduated from Bowdoin in 1877 with a degree in civil engineering, made an international name for himself as an early Arctic explorer. During World War II, his feats were memorialized in the naming of a naval SeaBee training facility (Camp Peary), and the USS Robert E. Peary, a naval destroyer escort christened by Peary’s widow, Josephine Diebitsch Peary, who had accompanied him on several of his polar expeditions. But it was the Liberty Ship Peary that would captivate the country.

In November 1942, employees of Kaiser’s Richmond, California, shipyard endeavored to break the existing speed record for assembly of a Liberty Ship. To do so, they first assembled the Peary’s some 250,000 parts into large sections weighing as much as 110 tons. At one minute past midnight on Sunday, November 8, workers laid the first piece of the Peary’s keel. Hundreds of laborers toiled around the clock for the next four days. At 3:30 p.m. on Thursday, November 12, the assembled Peary launched to great fanfare, including an a cappella choir. Its total assembly time was four days, fifteen hours, and twenty-nine minutes. And while the ship would still require several days of outfitting before it was ready to sail, that assembly time had nonetheless shattered the existing record by more than five days.

Newspapers from Seattle to Oklahoma City to Boston carried news of the Peary’s record launch. But officials at the Permanente Corporation were emphatic that the real accomplishment came from empowering its employees to innovate.

“We are not primarily trying to break records,” yard manager Clay Bedford told the United Press Association at the time. “Our main purpose has been experimenting in new prefabrication methods and, after receiving hundreds of valuable suggestions and time-saving inventions from our workers, we decided to try them all on one hull and see what would happen.”

THE SS PEARY was launched at a decisive moment in the war. That same month, just off the coast of the Solomon Islands, Allied forces were struggling against Japan in the Battle of Guadalcanal—what would eventually become one of the Allies’ first real victories in the Pacific. Meanwhile, in Russia, European forces were struggling to beat back Nazi Germany in the Battle of Stalingrad, a protracted and particularly bloody engagement that would eventually give Allied troops an advantage in the European theater. Casualties were growing on both fronts, forcing the United States to drop its mandatory draft age from twenty-one to eighteen.

In countless ways, Liberty Ships supported these and other campaigns. It was a role especially fraught with danger. Liberty Ships were notoriously slow, often making fewer than ten knots. They were most often deeply laden with cargo (a single Liberty Ship could carry as many as 2,840 Jeeps, 440 light tanks, or enough rations to feed sixteen million soldiers for a day). Crews comprised anywhere from thirty-eight to sixty-two civilian sailors, including bakers, able-bodied seamen, and carpenters. Down below, engine room workers were responsible for the continued maintenance of the ship’s power plant— smoke from a single engine could alert enemy combatants to a convoy’s location, and were a ship to fall out of that convoy, it would become easy prey to a German wolf pack. Convoys were under strict guidelines to keep smoke from emanating from the ships’ stacks while at sea, but wartime operating conditions made it extremely difficult to keep engines running well enough or to obtain consistent, clean-burning fuel to make that a reality. According to American Merchant Marine Museum statistics, of the approximately 250,000 merchant mariners who served during World War II, more than 9,000 lost their lives—a greater percentage than any of the four official armed service branches.

But the boon the ships gave to both Allied forces and civilians was profound. With a range of 20,000 nautical miles, Liberty Ships ferried troops to battles around the globe. They brought much-needed humanitarian supplies to suffering communities. And they carried salvaged remnants of planes and other military wrecks from the front lines back to the United States, where they could be recycled and repurposed for other war efforts.

The approximately 2,700 vessels produced as American Liberty Ships were neither designed nor constructed with the idea that they would serve beyond the war, says Josh Smith. But those that survived often went on to serve long after their anticipated life expectancies. They carried pack mules and their army handlers to the Mediterranean during the Greek Civil War. They served as floating hospitals and aircraft repair shops. Some were recommissioned as mine sweepers, surveillance vessels, or cadet training ships. Others joined the National Defense Reserve Fleet, also known as the “mothball fleet,” where they were laid up in case of national emergencies.

However, most Liberty Ships—including at least five named after Bowdoin College figures— were entered into the merchant fleet, where they returned to their intended use as cargo vessels. For decades, they continued to ferry nearly every conceivable cargo, from cement and chemicals to vehicles and grain. Long after they too were removed from service, their legacy as one of America’s most potent weapons in World War II has remained an indelible part of international history.

Kathryn Miles is an award-winning journalist and author of four books, most recently Quakeland: On the Road to America’s Next Devastating Earthquake. Her essays and articles have appeared in publications including The Boston Globe, The New York Times, and Politico, among others.

This story first appeared in the Winter 2021 issue of Bowdoin Magazine. Manage your subscription and see other stories from the magazine on the Bowdoin Magazine website.