Disinformation and the Freedom of Expression

By Tom PorterSuzanne Nossel began her talk by making one thing clear: disinformation is free speech and constitutionally protected under the First Amendment. “Our government, our Congress, is not powered to ban or punish it,” she explains, whether it takes the form of conspiracy theories, innuendo, or false claims about the election.

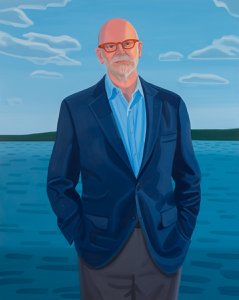

Nossel is the chief executive officer at the advocacy group PEN America. She is a leading voice on issues of free expression and maintaining democratic debate that is open but at the same time respectful of a rich diversity of opinions. She is the author of Dare to Speak: Defending Free Speech for All.

She addressed the Bowdoin community on March 1, in an online event moderated by Katie Benner '99, US Department of Justice correspondent at The New York Times, and viewed by more than 300 participants. This was the second in a series of discussions on the state of American democracy organized in the wake of the January 6 attack on the Capitol. The series is called "After the Insurrection: Conversations on Democracy."

Nossel said that, although disinformation is protected by the constitution, it can also present a threat to free speech, which is why it’s so important for a democracy to be aware of the difference between a robust exchange of ideas and the blatant spread of damaging falsehoods. “Rampant disinformation imperils the values and civic benefits that the First Amendment is intended to uphold, so even though disinformation is constitutionally protected, the fate of free speech and open discourse and maybe even of democracy itself hinges on our ability to get it under control,” she said.

The problem was exacerbated by former president Donald Trump, she added. “Through his cries of fake news and calling the media the enemy of the people, he worked systematically to discredit journalism and exhorted followers to disbelieve credible sources,” she said. “He pounded away at the foundation of fact-based discourse underneath his voters’ feet. Eventually they were left with nothing to stand on, clinging only to what he told them.”

This was a dangerous strategy, said Nossel, “unmooring a whole segment of the US population from truth and facts.” The situation was worsened tragically, she added, because “the Trump presidency coincided with a once-in-a-century pandemic. Primed to disbelieve not just journalists, but also scientists, academics, and experts…Trump supporters spurned the basic wisdom on how to control the coronavirus.” Trump, she said, instilled in his followers “a disdain for masks and other basic health precautions to the point where it didn't matter what the health leaders said—a portion of the population had become convinced that COVID was a hoax.”

“[Trump] pounded away at the foundation of fact-based discourse underneath his voters’ feet. Eventually they were left with nothing to stand on, clinging only to what he told them.”

Nossel also addressed the role played by social media platforms like Twitter and Facebook. Over the past year or so, these platforms have become much more active in policing the flow of information on their sites. “In the context of the pandemic, they have flagged, demoted, and removed speech that included false information that they judged could lead directly to harm,” she said. “This includes inaccurate claims about treatment or cures or claims that children don't get COVID-19 at all.” The platforms have also acted to promote more reliable information sources regarding the pandemic, such as the World Health Organization or the Centers for Disease Control.

When it comes to controlling the flow of political speech, said Nossel, life gets more complicated for the social media companies. Sites have gotten more aggressive in removing false information about voting, such as reports that you can vote online, or false details about opening hours for polling stations. However, she said, when it comes to political rhetoric, the boundary lines over what speech should be censored and what shouldn’t remain blurred.

It’s also important to remember that social media companies are not perfect, nor are they neutral, she added. “These platforms have their ideological biases. They rely heavily on artificial intelligence and machine learning, which can make mistakes.” Most importantly, said Nossel, they’re out to make a profit. “They’re private spaces… that make endless choices about what content to admit or remove.”

After her presentation, Nossel went on to answer questions from participants on a range of related issues, including the history of fake news, the “de-platforming” of controversial speakers on college campuses, and how to deal with a neighbor or family member “who displays untruths.”

Watch the event

The next webinar in the series "After the Insurrection: Conversations on Democracy" is on March 11, 2021, when legal scholar Myrna Pérez will talk about “Democracy, Voting Rights, and Elections.”