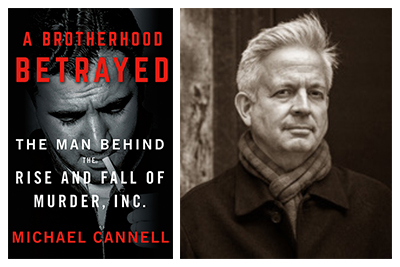

Author Michael Cannell P’21 on "A Brotherhood Betrayed" and Other Deep Dives

By Bowdoin NewsMichael Cannell goes deep. Whether it’s following the story of a serial bomber in 1950s New York—the pursuit of which resulted in what we now know as criminal profiling—in his book Incendiary or tracing the intertwining stories of a California mechanic who became the first American to win the Formula 1 world championship and his teammate and rival, a German count, in The Limit, Cannell brings to life stories from the past with immense detail and color.

What was your path to writing the story of real-life mobster Abe Reles?

A great writer named Paul Hendrickson (Hemingway’s Boat) once said that book authors can’t find subjects; subjects have to find book authors. Strange as it sounds, I’ve found that to be true. The story of Abe Reles, the greatest informant in mob history, dropped itself into my line of vision while I researched a previous book. Reles reminded me of a film actor you can’t take your eyes off. He sizzles with menace and malignant energy. I felt that immediately, and deeply, in my initial research. I describe him in the book as “giving off menace the way an oven radiates heat.” He scared even his friends—who were not true friends, as it turned out, but more like allies of convenience. So I pursued the book as a portrait of a certain kind of man—a monster, a demon, a golem—whose life ended in a mystery of retribution that will never be solved.

What sets Reles apart from other mafia bosses we read about, the Al Capones, the Bugsy Siegels, and the like?

When organized crime really got organized in the 1930s, its bosses—Lucky Luciano, Meyer Lansky, and others—appointed Abe Reles head of an assassination squad that came to be known as Murder, Inc. His job was to dispatch gunmen throughout the country to kill informants. No informants, no prosecutions—that was their operating strategy anyway, and it worked for about a decade. Reles staffed Murder, Inc., from the ranks of both Jewish and Italian gangs, which was a radical break from the strict ethnic barriers that had divided the underworld until then.

You describe some very dark episodes in mob life; what did you learn about the mindset of those who chose a path amid these ever-present dangers?

When Americans think of the mafia, they tend to think of The Godfather. The reality of Murder, Inc, was far grislier. They killed hundreds. They left bodies in the back of abandoned cars, most of them stolen, and dumped them in upstate lakes. In at least one case, they buried a victim alive. Strangely enough, in most cases, the assassins were also devoted family men who returned to dinner with wives and children after their grim day’s work. One of my favorite books about gangsters is titled But He Was Good to His Mother.

The detail in your books adds so much color to your telling of these accounts. How do you get to that level of description?

I normally conduct a great many interviews. All those voices enliven the book, breathe life into it. But in this case, I couldn’t find sources with firsthand knowledge of Murder, Inc. Most events in A Brotherhood Betrayedoccurred more than eighty years ago. So I drew the sound of people’s voices from contemporaneous newspaper clips, hundreds and hundreds of them. (My research also included FBI files and oral histories.) I spent weeks leafing through clips from the Herald-Tribune, New York Age, Daily Mirror,and other long-defunct newspapers. Through those clips I learned about such characters as the gunman Tick Tock Tannenbaum, Oscar the Poet, who read Nostradamus when he wasn’t disposing of stolen cars, and Evelyn Mittleman, known as The Kiss of Death Girl because all her boyfriends eventually died.

What attracts you to the stories you cover in your books?

That’s a hard question. I don’t think people should write books unless they’re willing to be obsessed with the story. If I feel the stirrings of obsession I know I’m on some kind of safe ground.

What drew you to storytelling?

I learned a long time ago that we’re not happy unless we’re employing our aptitudes. God knows I would make a hopeless farmer, banker, or repairman. Thankfully, I believe I’m putting my few aptitudes to work by telling stories about the past.

What was the biggest adjustment turning to long-form storytelling in books versus what you did for UPI, TIME, and The New York Times.

A conventional journalist tries to share all they know about a story with the reader. But an author writing in the style known as narrative nonfiction has to withhold information the way a novelist or filmmaker would. In other words, I try to borrow the techniques of fiction and apply them to journalism and history.

What is the best thing writing has taught you?

Always trust your instincts.