Willie Horton and Me, Again

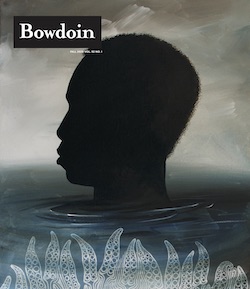

By Anthony WaltonIn the wake of the 2020 killing of George Floyd and a renewed global spotlight on racial inequity, Bowdoin professor and senior writer-in-residence Anthony Walton revisits an essay he wrote for The New York Times thirty-one years ago.

A political action committee had used ads featuring Willie Horton, a murderer, during the 1988 presidential election in order to frighten white voters, but it turned out to be much more than just a strategy to make one side seem soft on crime.

What I think about as I reread “Willie Horton and Me” now, thirty-one years after it was first published, is the way it represents the end of my innocence as an American.

At that time, in the summer of 1989, I was beginning to realize that much of what I had been taught by my parents and aunts and uncles, by my teachers and mentors, was a half-truth, a myth intended to encourage me to continue the journey of my people—by which I mean African Americans from the Deep South—on their quest to greater participation in the fullness of American life and society. I don’t think they intended to deceive, and I don’t know that I blame them; they were in a tough spot. How do you tell a young person the truth when you know the truth to be so brutal?

As I stared then at Horton’s mugshot on television, in the commercials, and on the news, in newspapers and magazines, even in the recesses of my own imagination, I could unconsciously and intuitively feel that that photo, with its menace of “the other” was going to, in a trick of neuroscience, come to represent me and every other young Black man I knew, and that the photo would come to be an avatar of all the other young Black men and women who have since died unjustly at the hands of the police and race-addled private white citizens. That photo boiled everything down to its essence: We were, and are, a threat. We are the threat. Horton’s aggrandizement in political advertising, as an icon, as a specter of the lawless African American, was, plainly put, blunt dehumanization, and it was most chilling to me because this image, this stereotype, was being put forward by men, including then Vice President George H. W. Bush and his staff, who purported to be stewards of the nation.

Think of it this way: When the heinous Charles Manson, or the despicable Richard Speck, or the recent double murderer Roy Den Hollander, or any other white criminal is portrayed in the media, they are not then projected as representative of all other white males and as a putative dire existential threat to our well-being as a community and nation. It is not implied that they, in particular, by their mere existence, represent a threat that onehalf of the political structure (the Democrats, in this case) cannot be trusted to control and contain. It is not even implied that white males need to be controlled and contained, though, given the recent activities that some of them are accused of—such as the murder of Ahmaud Arbery and the plots to kidnap Governors Gretchen Whitmer and Ralph Northam—one might ascertain and argue that they need to be. No, the crimes that white men commit are presented as tragedy, oddity, quirks in human nature, sociological problems to solve and remediate. Willie Horton, on the other hand, was presented as a threat to the very fabric of our nation’s existence; by implication, he was representative of all Black men and, ergo, how Black men and women also represent, embody, that fatal threat.

And I do not think this is an exaggeration.

But I am getting ahead of myself.

When I wrote “Willie Horton and Me,” a year after the 1988 campaign, I was becoming aware of my true place in American society and the fact that, no matter what I did or how I acted or whatever I accomplished, a significant percentage of Americans would link me to him. It would be years before I would learn various salient facts around how that benighted man, Willie Horton (even the name rings like a Southern cliché, as it conjures a demented outlaw “darky”), gained his place in our mythology and folklore. But I was starting to feel it.

When I wrote the essay, I didn’t know that it was a deliberate and intentional maneuver by 1988 Republican presidential campaign strategists to “sow the wind,” to borrow a scriptural metaphor, and gain political advantage by inciting the fears and paranoia of just enough white voters to tip the election in their favor. I had my suspicions, which I adumbrated in the original essay, but those suspicions would be confirmed by one of the architects of the strategy, Lee Atwater.

Shortly before his death in 1991, Atwater (rather clinically) explained to political scientist Alexander Lamis what he and his fellow strategists were thinking as they developed the ad: “You start out in 1954 by saying, ‘N——r, n——r, n——r.’ By 1968 you can’t say ‘n——r’—that hurts you. Backfires. So, you say stuff like forced busing, states’ rights, and all that stuff. You’re getting so abstract now [that] you’re talking about cutting taxes, and all these things you’re talking about are totally economic things, and a by-product of them is [that] blacks get hurt worse than whites. And subconsciously maybe that is part of it. I’m not saying that. But I’m saying that if it is getting that abstract, and that coded, that we are doing away with the racial problem one way or the other. You follow me—because obviously sitting around saying ‘We want to cut this’ is much more abstract than even the busing thing, and a hell of a lot more abstract than ‘N——r, n——r.’”

I think that stands as evidence; one of the two major American political parties has deliberately, for more than fifty years, fanned the fires and divisions of racial hatred and misunderstanding. As their plan.

Consider a statement made by Trump supporter Crystal Minton, who said to New York Times reporter Patricia Mazzei in reference to Donald Trump, “He’s not hurting the people he’s supposed to be hurting.” She was complaining that the 2018–2019 government shutdown, implemented by Trump, was harming her and the people of her small town, who were largely dependent on government jobs at the federal prison in Marianna, Florida. In Minton’s statement, we hear the revenant of Atwater’s remark: “Blacks get hurt worse than whites.”

But by 2019, the subtext had become the text. Atwater had played a very large role in this GOP battle plan, often referred to as “The Southern Strategy,” architected in 1968 by the Nixon campaign to use race as a wedge issue. But I didn’t know that, not for sure, in 1989. In 1989, it was painful and bewildering. And, looking at it from the vantage point of 2020, I didn’t know that not only would it continue over the next thirty years, but it would get ever more sophisticated and savage, turned to cringing effect against Barack Obama and finding (one must hope) its apotheosis in the mind-numbingly regular statements and taunts of Donald Trump. I have to say, as an intellectual proud of what I think of as my sophisticated irony, it would almost be funny, like a Saturday Night Live or Dave Chappelle skit mocking outdated ignorance, if I were not the parent of a child who has had her childhood blighted by all this.

I also didn’t know as I wrote, and neither did many others, that the officer who apprehended Horton and brought him to justice, Yusuf A. Muhammad, was African American. Muhammad, a corporal in the Prince George’s County Police at the time, shot and wounded Horton, bringing him in. That wasn’t in the ad. It also wasn’t in the ad that Corporal Muhammad was the recipient of two degrees from Johns Hopkins, that he would go on to be a police chief, or that he would finish his illustrious career with the Metropolitan Police of Washington, DC.

The everyday occurrence that the best and worst of our society, a valiant and studious and learned police officer and a vile criminal, were of the same race had been conveniently overlooked by the Republicans in their rush to stereotype Black males. And perhaps it points to what I have come to think of as the general incompetence on these matters of the Democratic Party and their strategists that they did not make an advertisement pointing this out. But what we were left with was a masterpiece of cruel political magic stirring up fear and division that went virtually unanswered and that has been allowed to morph and metastasize over the succeeding decades.

Everything I have said up until this point in this essay is context: I think it is extremely important that we, all of us, remember just how big and deliberate all the circumstance involving and surrounding “Willie Horton” was. You can call me naïve, or you can call me the son of parents who believed in American possibility or who had no choice but to believe, because they had nowhere to go but up. We were, as a family, from the fields of Mississippi, caught up in the Great Migration, so we embraced opportunity wherever we could find it, and kept pushing, trying to make a place in America for ourselves and for our descendants. And we, basically, did.

But we also paid a price, as we had to become detached, even cynical, as we learned what too many of our fellow citizens thought of us, and as we continue to learn today. In our minds, we carry a skein of voices, the poignant pleas of African Americans for their lives and the brutal assertions of white supremacy:

I can’t breathe.

There were fine people on both sides.

He’s not hurting the right people.

In 1989, I was naïve—I did not understand that there were substantial numbers of American whites who were basically unpersuadable on the issue of racial equality, who would view any progress or advancement by African Americans and other Americans of color as a setback for themselves, who would embrace stereotypes and unfair castigation. And by saying I was naïve, I don’t mean to imply that I have by now figured things out. I am regularly startled and often surprised by things that happen in the racial realm in our country, and I have come to realize over the intervening decades that what can only be described as white supremacy—the belief that America is, ultimately, of, by, and for the benefit of people with skin that is described in our vernacular as white—is inscribed in the metaphoric DNA of our nation.

In my belief, that mode of thinking is so deeply inscribed in the genetic material of our nation that it will not—cannot—ever be fully excised. It is something that we, those who do not believe in or support the doctrine of white supremacy— Black, white, Latinx, Asian, Indigenous—have to regularly, constantly fight against.

Unfortunately, one of my ways of fighting has been to learn to avoid situations that can become humiliating, provocative, or stressful: situations where I cannot, will not, be seen as an individual. Rather than push against an insurmountable wall, I have wagered that it is better to develop a detachment that preserves psyche, soul, and blood pressure. This particular lesson was hammered home to me by an incident that occurred in late 1998, almost ten years after “Willie Horton and Me” appeared. I had scheduled a lunch with my close friend who was a celebrated psychiatrist and fellow at Rockefeller University in New York City. This is not “name dropping,” but again necessary context, because we were scheduled to have lunch at Rockefeller that day, where we would sit down with, among others, the renowned physicist Murray Gell-Mann.

So maybe I was feeling a little full of myself, thinking that I was moving ahead in the world. Maybe I was forgetting the lessons I had learned because I was in Lower Manhattan as lunchtime approached and needed to get to the Upper East Side location of New York Hospital, where I was to meet my friend and walk to lunch. But, as I relate in the original essay, I needed a cab.

Suffice it to say, I did not secure a cab ride even though I was expensively, in my mind exquisitely, attired in a suit, with the same trim military style haircut. The rest can be inferred by what I describe in 1989. What was different in the incidents is that when I finally made it to our rendezvous, running late for lunch, my psychiatrist pal stopped me and asked why I was so angry. I said, “You know why I’m angry.”

“Why are you so angry?” he asked again.

“You know why I’m so angry,” I said again.

“I think you’re angry because you are a masochist,” the good doctor said playfully. I told him I didn’t know what the hell he was talking about. But he did. He said, “Listen. You know what is going to happen if you try to get a cab. Yet you tried to get a cab. Why didn’t you take the bus? Ride the subway? Walk?” He looked at me carefully, with both concern and love. “Why are you risking your health by fighting something you can’t change?”

In that instant I began to understand what African Americans call, among ourselves, the “Black Tax,” which is not only what we have to do extra, but also what we cannot do, what we must accept.

And I can’t get a cab, or do any number of other things, because of what too many people think about Willie Horton, which is part of what they think about Black men, and Black women.

So, I leave early. I take the subway. I walk. I make sure I don’t “scare” anyone in the subway or supermarket parking lot after dark (or in daylight), even though what I am is a bookish middle-aged duffer mostly concerned with getting home so I can have some decaf and read novels. I don’t know, or perhaps more accurately, haven’t decided, whether or not this sort of racial prudence constitutes a loss of liberty, because it also counts in my book as a loss of liberty to endure suspicion, emotional assault, and deliberate humiliations. So why not avoid them if you can? And perhaps, in this current national context of renewed racial hostility as reinforced by a president who smirkingly tells the white supremacists to “stand by,” this is not just weary prudence, but active self-preservation.

I have realized that we African Americans often have to live inside the paranoid or delusional psychomachia of those whites who are preoccupied if not deranged by race. I think of the unarmed Black man in Minnesota, gunned down on May 1, 2020, by a white man after a minor car accident, just weeks before the murder of George Floyd. The gunman was twenty-four and claimed to be “in fear for his life,” a statement vehemently disputed by witnesses and Good Samaritans at the scene.

The unarmed man who was murdered was named Douglas Cornelius Lewis. His death wasn’t filmed, so it did not join the legion of martyrs that we as a nation know about and grieve. According to the St. Paul Pioneer Press, Lewis, a father of four and delivery driver for Amazon, had exited his vehicle after a fenderbender and was approaching the other vehicle when he was shot, by the other driver, from ten feet away.

It’s astonishing to discover as I did decades ago, and then to be reminded—yet again—that one’s mere conduct of daily life can provoke outrage, fear, contempt, and even murderous violence. And that has to do still, I think, with Willie Horton as the apotheosis of a vision of Black persons born out of the crime of slavery, propagated through the centuries, and deployed until this day. And I don’t have any solution. And I don’t have any plan, other than to train my child for what she will face, to teach her what we African Americans have always taught our children about love, strength, and resilience, because it has become clear to me that this circumstance, 400 years in the making, is not going to go away.

Anthony Walton is author of Mississippi: An American Journey. His poems and essays appear widely, and he has received, among other awards, a Whiting Fellowship.

This story first appeared in the Fall 2020 issue of Bowdoin Magazine. Manage your subscription and see other stories from the magazine on the Bowdoin Magazine website.