Inhabited: The Story of Malaga Island

By Surya Milner ’19Less than ten miles from Bowdoin as the crow flies, just a short distance from the Phippsburg shore, Malaga Island was once home to a small fishing community established by descendants of a freed slave, all of them forced from their homes by greed and state-sanctioned intolerance. Nature is Malaga’s only resident now, but the presence of those who lived on the island lingers.

Against a backdrop where Maine’s beauty meets a startlingly ugly period in our state’s history, Surya Milner ’19 sought to understand her own place, in Maine and beyond.

When large gusts sweep in off the Atlantic, the time-worn crags that guard the shore of Maine’s southern coast stand firm against both wind and wave. Over the years, these lands have witnessed native Abenaki, English colonists, French missionaries, summer tourists and boaters, and asylum seekers.

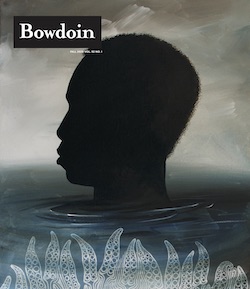

Photographer Séan Alonzo Harris, who is Black and has a mixed-race family, saw metaphors of the long-gone Malaga residents in the island’s current life.

Our photo captions explain the ways Séan expresses those ideas in his images.

It’s said that Benjamin Darling, a slave on a New England merchant ship, saved his master when the ship collided with this jagged shore in the 1790s. In return for saving his life, Darling’s master granted Darling his freedom and his name, and Darling settled nearby. A fair and upright citizen, he was a reliable worker at the local salt mill. He was mauled by a bear while trying to defend his neighbor’s corn patch. Eventually, he bought his own island, Horse Island. Fifty years passed, and the Civil War had reached its end by the time Darling’s granddaughters made a home on their own island, half a mile to the north of Horse, forty-one acres without a name.

Originally home to those granddaughters and Darling’s other mixed-race descendants, the island soon blossomed into a multiracial fishing community. Intermarriage was illegal, but the white mainlanders of nearby Phippsburg pretended not to notice—at least in the beginning. For those whose connections to the place run deep, the story of Darling’s granddaughters and their families is a tale of a quiet island community, “dyed in the wool,” that subsisted on what the Atlantic could offer and committed to teaching their children how to read, write, and eke out a life from the sea.

They called the island Malaga.

I came to Maine for college, a girl who shaded in the bubble for “two or more races” on the SAT, who left Texas for the whitest state in the nation. I was startled to view the coastline, to see the pines open up before me, to know a landscape that is both vast and deep.

Although it is often said that there are “two Maines,” there is an abundance of progressive history here: Harriet Beecher Stowe wrote much of Uncle Tom’s Cabin in the white clapboard house at 63 Federal Street, which the College now owns; one story claims that she read passages to celebrated Union general Joshua Chamberlain, Class of 1852, the war hero, Maine governor, and Bowdoin president who was known for his valor at the Battle of Gettysburg. This history is a part of everyday life at Bowdoin: To enter campus from downtown Brunswick, you pass a statue of Chamberlain in a town plaza outside the campus gate; and historians seem sure that Brunswick was a stop on the Underground Railroad. Yet it was here, not in Texas, that I found myself confronted by carefully couched questions while I was waiting tables or reporting for the local paper.

The questions were always variations of the same: Where are you from? And why are you here?

The answer is neither linear nor easy to weave into casual conversation. “My mom’s from India,” I grew accustomed to saying, and leaving it at that. But inwardly, I found myself obsessed with quantifying my own identity: half-white, half-brown, part-Indian, mostly American, not Hindu, raised Christian, speaks broken Arabic; no, not Muslim either. How many times could I splice myself on the basis of imagined biological facts and the cultural codes they carried? They are constructs, and yet I molded myself around them, every day.

The world often presented narratives of race as monoliths—Black, white, brown—but I found fewer lampposts for being mixed-race. If I could find an exact story to match my complexity, perhaps I, too, could fit into a larger narrative, make sense of the world around me.

Then, sifting through old issues at the Portland Press Herald, the newspaper where I worked, I found Malaga. There were other people here once, living on an island twenty-five minutes away from my predominantly white town, people who confounded the essentialist ideas of race I kept encountering. I knew that I could not lay claim to Malaga’s history: I am neither Black nor a Mainer. But I wondered if learning about the descendants of this island might help me consider and navigate the experience of being a mixed-race person in this very white state. Perhaps, if I listened long enough, the island’s history could help me learn how to inhabit two spaces in one.

Born across from the sardine factory in South Ferry, Portland, Marnie Darling Voter was disguised as a boy until the age of twelve. Only boys could be on the dock, and her father needed help fishing and hauling traps. Other days, she would go crab picking with her aunts. Later, Marnie, who is white, became a hippie, she says, and ran off without a destination—just a desire to live freely.

Everything changed years later on the day that Marnie’s late husband, Delmar, took her to peruse the genealogy records at the Augusta library, a straight shot up the interstate from Portland. Marnie was twenty-one years old and had never heard of Malaga. Leafing through the records, she found the link between herself and her last name: a Black man named Benjamin.

“I called my father immediately,” she says. “He told me to shut the f—k up and never mention it again.”

Like many descendants of Benjamin Darling, Marnie’s father had been shamed into silence, but Marnie kept searching. She found out what happened to Darling’s descendants, a story that other local residents said was “best left untold.”

In the years after the island’s founding, hundreds of sensational accounts circulated about it, spreading claims of ignorance and contamination. A 1902 article from the Bath Enterprise, a local newspaper, condemned Malaga in the name of religious purism: “No worse heathenism we imagine could be found in far off heathen countries than can be found on this godless island.” Another article from the Casco Bay Breeze described the island as “the home of southern negro blood . . . [an] incongruous scene on a spot of natural beauty.” Word of Malaga spread south as mainlanders grew fixated on an island that they believed marred the state’s idyll. Without these “incongruous” outliers, Maine might be easier to sell to tourists; shipbuilding, the backbone of the regional economy, was dying, and a tourist economy beckoned. Perhaps, without the island’s residents, Malaga could be made into a resort.

The interracial island community was nearing forty members when Maine Governor Frederick Plaisted told them to leave. The residents were too poor, according to the state, and too dark; within the framework of the emerging eugenics movement, the two were made out to be akin to immorality.

In 1912, the county sheriff delivered the official notice: The islanders would have thirty days to leave Malaga and take everything, even their homes, with them.

Some floated their homes to the mainland, where they docked on a landing that a number of Phippsburg residents would call by a name that is both derogatory and offensive. The state government took others to the Maine School for the Feeble Minded. And the bodies of those who had lived and died on Malaga were unearthed, taken by boat, ferry, and then stagecoach to the same state-run mental institution, and interred there. The island was left barren. It has hardly heard the voices of humans since.

I am looking for Marnie, but all I can see is fence. I continue driving for two miles and then I am there, face-to-face with a stone sign that reads PINELAND, taking in the red brick buildings with their blinding white details. Pineland Farms is a destination for cross-country skiers in the winter, for Maine weddings, for those interested in sustainable agriculture. It is a five-thousand-acre campus of farmland, cottages for rent, a market, and a business center.

It is also, Marnie tells me, a place of annihilation. All it took to get committed to Pineland—when it was known as the Maine School for the Feeble Minded—was the unanimous approval of a doctor, a sheriff, and a judge. For the ten or so Malaga residents who were brought here, already stigmatized, it wasn’t hard to get the stamp of all three. Some were forcibly sterilized.

They, along with the remains of the disinterred people of Malaga, are buried at Pineland—but even here, they are not equal. Divided in two parts, the cemetery is an object lesson in historical erasure. The front section, a conventional burial plot for mainlanders, faces the road. In a meadow beyond, facing the woods, lie those who were evicted. The tombstones there look like paint chips, and memorial plaques are placed haphazardly in a square area—maybe six-by-six yards—as if they were built at different times and for different reasons, placed there by people grappling with the past in different ways.

The largest memorial spells out the names of the islanders, one by one, and paints the fullest picture of what happened on Malaga. It was dedicated by the state in 2017, only two years before I made the visit with Marnie. The story is written on the stone: “From the 1860s until 1912, a community of laborers and fishermen lived on Malaga Island off the coast of Phippsburg. A controversial community for its time, white and black residents married and lived together on the small island until the state of Maine evicted them in 1912. Included in the eviction was the state’s removal of the island cemetery to the grounds of Maine School for the Feeble Minded, where some island residents were committed. Remembered here are the community members exhumed from the Malaga Island Cemetery by the state and those who died here as patients.”

My eyes hover over the words for its time. I wonder if Malaga and its people aren’t considered controversial for our time, too: The story has been stifled for a century, but, depending on who you’re talking to in Midcoast Maine, the word Malaga can still be a slur.

Marnie surveys what’s left of her ancestors, small outcroppings of stone. Today, she is one of the most vocal advocates, the one who remembers the names by heart: Ben, Isaac, George, George, William, Leonard. She rattles off the list, six generations of Darling patriarchs, ending with her father, without skipping a beat. When speaking of the memory of the island today, she suggests that those buried here should be returned to Malaga. Their bodies might rest easier there. But then again, she says, they’ve been through enough already.

Among the hundreds of known descendants of Malaga, only one family is Black. They are the descendants of Harold Tripp, a man who, at the state’s orders in 1912, sailed away from his home on the island. He was six years old; his mother died at sea.

Gloria, Harold Tripp’s daughter, grew up in Augusta, Maine, but didn’t know a thing about her connection to Malaga until a few years ago, when a reporter started piecing together their shared family tree. Gloria doesn’t remember much about her father except for his temperament. “My dad was a very angry man. [Angry] at white people. Because there was nothing [in Maine] but white people,” she tells me over the phone. “I don’t think Maine has a special love for Blacks, or anyone else who’s not of the white race. They never have and they probably never will.”

Maine is changing, some say. In the news, Gloria reads about refugees coming to Maine, a steady stream of African immigrants, many from Somalia. Between 2000 and 2010, the state’s nonwhite population increased, according to the Bangor Daily News, mostly in the south and near the coast. Still, the state can be a difficult place for outsiders, or those perceived to be outsiders. By the time Gloria learned of Malaga, Maine was only a memory. She had moved away, partly because she grew tired of the separateness and otherness she had long felt. The history of the island lives on in those who are still able to call Maine home—like Marnie—as well as those who, like Gloria, chose not to stay.

One afternoon in late April 2019, I make the trip to Malaga. Marnie, busy caring for her grandchildren today, can’t come with me. Neither can Gloria, who now lives in Connecticut. So, I go without them, on a little skiff, accompanied by a woman named Caitlin Gerber. Caitlin is thirty, pregnant with her second daughter, and a land steward at Maine Coast Heritage Trust. Malaga is one of hundreds of properties owned by the trust.

Caitlin calls the landscape of Malaga “magical,” and through the spring mist I can see what she means. The island is lush. Moss spreads over the forest floor, and spruce trees shoot into the sky. And then there are the shells, crushed into smithereens, white and glinting, strewn along the shoreline: a reminder of the people who harvested clams here a century ago. After a long winter, everything is alive and covered in soft dew.

I am sad that neither Marnie nor Gloria are with me now, taking in the white shell beach or resting on the rippled rocks that jut out into the bay. Though the island is a public preserve, rarely do descendants make the trip. They, like Marnie and Gloria, have built new lives in new places. I know that there are many more who I may never meet, who straddle the space between the island’s ghostly past and growing present.

But there’s something about standing next to Gerber—trying to match our shoddy map with where we’re standing, hoping to pinpoint the place where homes once stood—that makes sense. We’re both outsiders, tenuously connected to this tiny community that stood a little too close to the mainland, trying to make sense of a story that, like the tide that pulls our skiff away from us, recedes with the passing of time.

I think back to Pineland, where Marnie asked me what I thought. Of all of this? I wondered. I told her that the story was too heavy, too grotesque to fathom.

Standing on Malaga now, the picture is fuller, clearer. Drawn to Malaga by the history of its inhabitants, I realize I was seeking some sense of solidarity. But my projections—about these people whose pasts I had pored over, and the codes linking them to me—had begun to splinter. Those who called Malaga home cared less for rigid racial narratives, I’d imagine, than others of their time. Yet it was because their existence violated the racist “rules” of their time—rules that still have an impact on many of us, in many ways—that their island is now empty.

“Malaga reminds me: Our bodies draw no borders, nor fences, nor fine lines.”

Why had I sought to articulate my identity—trying to split myself up into little percentages of white and not white—by using a bigoted framework akin to the one that justified the removal of people from Malaga? I had conformed to the language of cold categorization, standardized test questions, to tell me who I was. The existence of this island, and the people who lived here, shows the inadequacy and harm in those narrow definitions.

And it is a violence that has been buried deep. Malaga didn’t open my eyes to injustices committed against Black and brown people, but such loathsome history is presumed by many in Maine to be imaginary, or at least hidden. So erased from accounts of Maine’s racial history was Malaga that finding it, for me, feels like the bridge between what Maine professes to be and the hefty weight of its iniquitous history. Looking at Malaga, Maine’s whiteness and seeming progressivism make sense. It has silenced, and then shamed, those with another story to tell.

The water is still as we motor back. For a moment, it appears that we are skimming the reflected clouds above us, not ocean expanse.

We chat about the people Caitlin has encountered over the years—the local artist who envisions a community center on Malaga; those who want to see the island unchanged; the descendants who want to see the bodies of their ancestors returned. I feel the weight of a great silence, and the imperative to tell a story that is truthful, that accounts for the story of Malaga— and Maine—as it truly was and is.

Surya Milner ’19 is a freelance writer living in Los Angeles. This story originated in a long-form writing class with professor Alex Marzano-Lesnevich, and a version of it appeared in Catapult magazine in August.

Séan Alonzo Harris is an award-winning commercial, fine art, and editorial photographer living in Waterville, Maine. See more of his work at seanalonzoharris.com.

This story first appeared in the Fall 2020 issue of Bowdoin Magazine. Manage your subscription and see other stories from the magazine on the Bowdoin Magazine website.