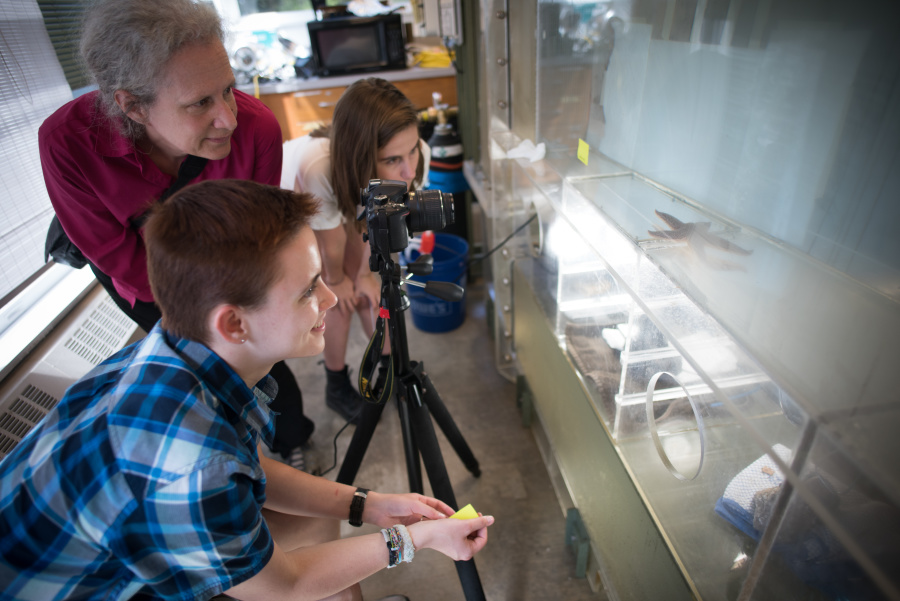

Professor Amy Johnson's Sea Stars Gallop to Fame

By Rebecca Goldfine

Although most people encounter sea stars (also known as starfish) lying almost motionless in tidal pools, they're actually nimble hunters "that scour the oceans for prey," the KQED/Deep Look report explains. They can also run to escape predators that want to eat them.

They move with the help of hundreds—and sometimes thousands—of small tubular feet. These little feet also help them sniff out nearby food without the need for a brain.

Johnson and her research partner, Research Associate in Biology and Mathematics Olaf Ellers, have made breakthroughs in the area of sea star movement, revealing for the first time the two distinct ways sea stars move, and thus survive. When they're excited, sea stars can pick up their pace from a crawl by bouncing. To do this, many of their tube feet simultaneously lengthen and stiffen, lifting the creature up midstride and vaulting it forward.

“It was an absolute epiphany,” said Johnson, describing the moment when she and Ellers first understood the mechanics of sea star movement.

Since then, Johnson and Ellers have joined a bicoastal collaboration that may one day lead to the invention of robots that mimic the movements of sea stars. These machines could more thoroughly search shipwrecks, clean ocean vessels, and explore the bottom of the ocean.