Quiet for Days: Will Bucci ’19 and Six Months of Meditation

By Rebecca Goldfine

After graduating from Bowdoin last May, Bucci was uncertain about what he should do next. "I didn't want to jump into a full-time job without first establishing a strong internal grounding. I thought I would take time to travel and explore," he said.

He began putting into place a plan to work on an organic pineapple and coconut farm in Hawaii. But a suspicion nagged at him. "I asked myself, am I going to Hawaii because I am generally excited to go? Or maybe because I am not totally satisfied with where I'm at, as a person, in life. Maybe I am looking for an external fix to an internal problem," he said.

So he begin to lay the groundwork for an internal experience, a spiritual quest. From September to December, he traveled to eight monasteries and meditation centers to study different Buddhist traditions. He began at Temple Forest Monastery in New Hampshire on his birthday. From there, he went to centers in Massachusetts, Virginia, West Virginia, Maryland, British Columbia, and California. All were donation-based, Bucci said, leaving his only expense the travel to and from each center.

"I wanted to start my twenty-third year of existence going all the way into this meditation thing and see how far I could take it," he said.

By wintertime, he was flying to Myanmar for what would become a sixty-five-day silent retreat at the Panditarama Hse Main Gon Forest Center in Bahan Township.

Sixty-Five Days

Wake up at Panditarama was at 3:00 a.m. ("Mind you, I had been waking up early at other monasteries," Bucci said. "My wake-up game was in shape by this point!")

The fourteen hours of daily meditation began half an hour later, at 3:30 a.m. Breakfast was served at 5:30 a.m., and lunch at 10:30 a.m. No solid food was consumed after noon. The last scheduled meditation was at 9:00 p.m., with bedtime a half hour later.

Bucci lived, ate, and meditated with about seventy other men. Women resided on the other side of the monastery. All cell phones were relinquished at the start of the retreat.

"We weren’t supposed to look at people, talk, or write notes," Bucci said. They did, however, have a daily verbal check-in with a teacher. "The instruction was, this is your internal experience, and you need to lean into that as much as you can."

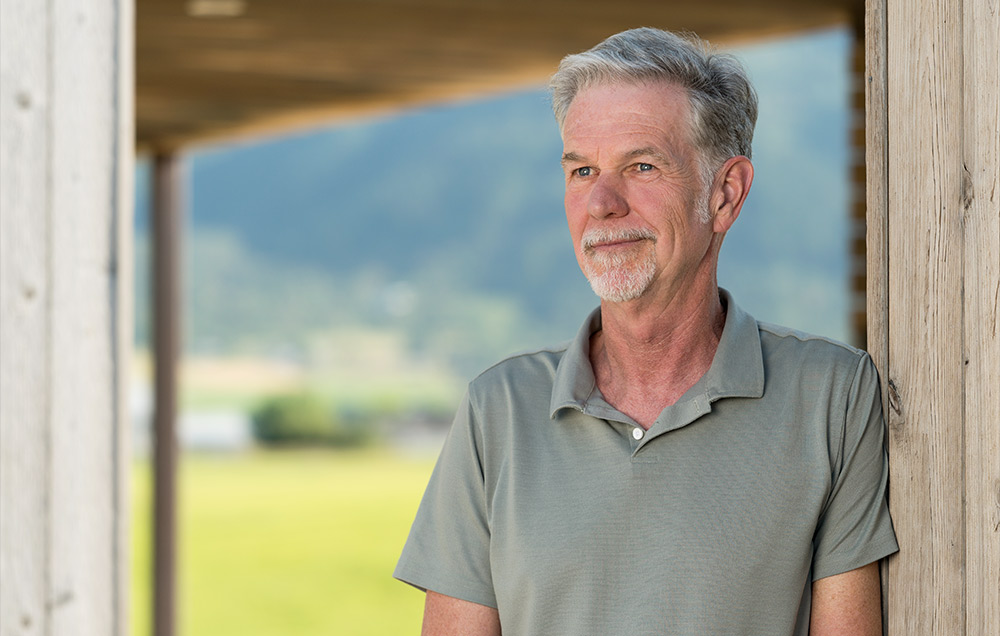

For those who know Bucci, the idea of him remaining quiet for such a long period of time comes across as just short of miraculous. He's exuberant, and exudes confidence and an overflowing joy. "Honestly, in normal life, I am outgoing and talkative, but in these retreats I settle into the silence fairly easily," he said. "It wasn’t much of a struggle, partly because I had this training beforehand."

Practicing mindfulness at Panditarama extended to all activities, including mealtimes, washing clothes, and resting. The monks and nuns encouraged practitioners to tag a mental note onto everything that rose to their awareness, like the rise and fall of the abdomen with breathing, and lifting up a spoon to eat.

"Normally at home I eat a meal in between ten and fifteen minutes. At this monastery, I took close to forty minutes to eat most of the meals," Bucci said. (Now that he's back at home in West Gardiner, Maine, he "squeezes in a mindful meal every now and then." But mostly, "I'm back to sucking down my food!")

The changes that come from such an experience can take time to unfold. But Bucci is already different, his outlook on himself slightly shifted.

Initially, his expectations for self-transformation were high. "I guess I had this idea I could do this epic quest and be this mystical, sage guru," he said. "I wanted to master my mind, have complete control over my thoughts, have epic concentration powers, and not be swayed by the stresses and anxieties of our crazy lives." At times, he considered becoming an ordained Buddhist monk.

While he ultimately decided not to become a monk, and he didn't achieve mystical mental powers, he did discover an important truth for himself.

"Overall, I don’t know if I really experienced anything super unique or anything I have never experienced before on this retreat," he said. "But the degree to which I was able to engage with feelings was so much higher than in daily life."

"In our daily lives we have stress, anxiety, frustration, love, euphoria, and peace....These silent times gave me the ability to dive into these moments, become intimate with them, and learn the nuances of these internal landscapes we’re always navigating." Meditation has taught him to observe his emotions and watch them as they rise and fall away, rather than jumping to act on them.

Though his stay in Burma was cut short by the COVID-19 pandemic (he flew home in late February), Bucci had begun to wonder by then how much good could come from continuing to push himself. "I was giving meditating my all, and I could have continued doing that, but you do reach a point of diminishing returns," he said.

Maybe, he thought, he could adopt a gentler approach. Instead of meditating fourteen hours a day, he could do it one hour a day in a comfortable environment.

"I thought that the only way I could get to where I want to be was by being a Buddhist monk. But I can get to that place by teaching music in a high school or opening a bakery," he said. At the moment, he's focusing on writing and playing music, and eventually would like to go to graduate school to become a psychotherapist.

"Our human experience of life in general is not necessarily governed by what we’re doing, but how we’re engaging with it," he said.