Capturing a River

By Tom Porter“No man ever steps in the same river twice.” Michael Kolster says this quote from the Greek philosopher Heraclitus perfectly sums up his longstanding fascination with rivers. “They’re amazing metaphors for time and change and a great subject for a photographer.”

Kolster’s latest book, L.A. River (GFT Publishing, 2019), contains a series of images of the fifty-one-mile body of water at various stages, from its headwaters in Canoga Park through California’s biggest city to Long Beach, where it meets the Pacific Ocean. For this project, Kolster used a nineteenth-century photographic technique called the wet plate collodion process, to striking effect.

It’s not his first exploration of the river as a subject. Kolster’s previous book, Take Me to The River: Photographs of Atlantic Rivers (George F. Thompson Publishing, 2016), chronicled four American rivers that flow into the Atlantic, as they emerge from two centuries of industrial misuse and neglect.

Why the LA River?

“A river is an incredible embodiment of change and a great model for how we perceive change over time,” said Kolster. “Something is flowing through a river that will never do so again, and as a photographer I want to call attention to this.”

While working on Take Me to the River, Kolster says he became curious about West Coast rivers. “I decided on the LA River because it’s such an odd example of a river. It comes out of the San Fernando Valley, where it’s formed out of several creeks that empty into it, through the middle of the city into a huge watershed.”

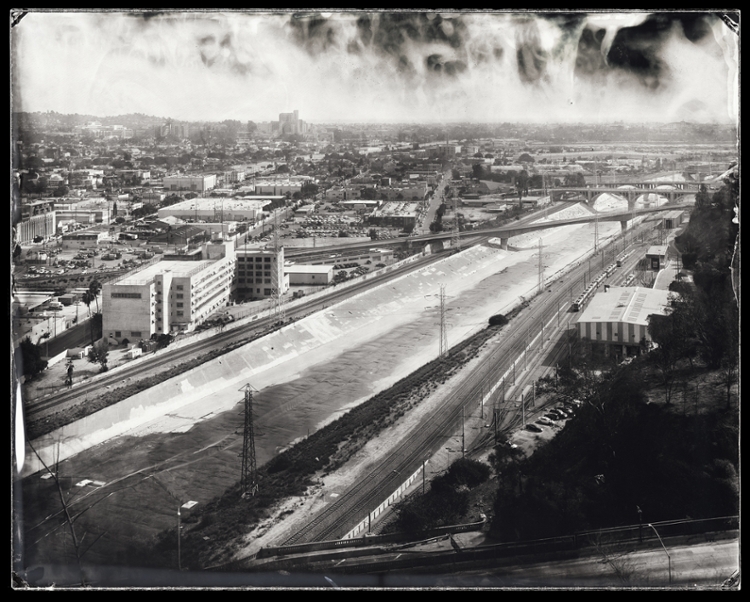

The river was channelized by the Army Corps of Engineers in the 1930s to try to control the flooding that occurs with such a huge watershed, said Kolster, which notably changed the character of the river. “The result is that most of it is now encased in concrete, and many Angeleños now grow up either not being aware there was a river in their midst, just viewing it as a drainage canal, as most of the time there’s just a small amount of water running through it.”

There is increased awareness of the river nowadays, said Kolster, with a major push for environmental regeneration getting underway over the last decade or so. “The architect Frank Gehry has spearheaded efforts to revitalize the LA River, with plans for river parks and open spaces along its length. Nevertheless, the river still has major quality challenges through agricultural and various kinds of nonpoint source runoff.” Part of the river also runs right along some of LA’s major freeways, said Kolster. “Hundreds of thousands of cars pass along it every day, which is its own kind of river.”

The Appeal of the Wet Plate

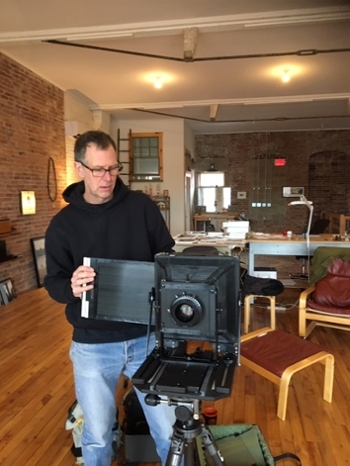

Wet plate is a labor intensive and lengthy process, involving up to three hundred pounds of equipment and material, and Kolster is only able to make about ten to fifteen plates per day when he’s on a shoot. So, what’s the appeal?

He started using wet plate photography around 2011, he explained, as an indirect consequence of the rise of digital photography. “I love being in a darkroom and developing my own photos,” he said, “but, as digital photography became ubiquitous, it got harder to access the materials I needed: Most of the manufacturers that produced the film and paper I used stopped making it or went out of business.”

While Kolster embraced digital photography, he also wanted the option of working chemically with photosensitive materials. This brought him to the wet plate collodion process, as it’s called. Invented in 1851, it involves coating a glass plate with a chemical mixture then bathing it in silver nitrate to make the plate photosensitive. “You can prepare your own film, with glass instead of paper, using ordinary materials you can get anywhere.” Once it’s prepared, the plate is exposed for up to a minute before being developed in a darkroom, or tent if you’re in the field.

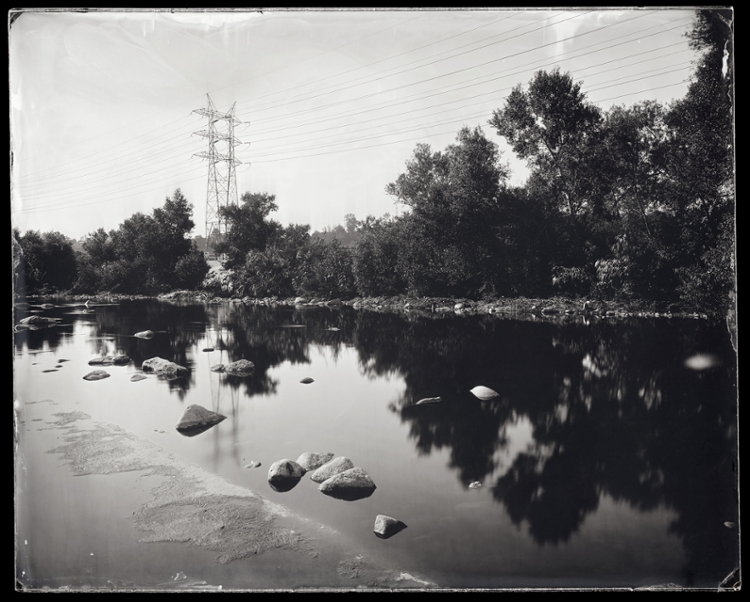

The type of image produced by Kolster is known as an ambrotype, he explained. The final product is an underexposed glass plate on which the picture is a barely visible until viewed in front of a black background. Ambrotypes are, like paintings, unique objects in that there is only one original. “There is one glass plate,” he commented, “and it’s a unique object, which I love because it flies in the face of how we usually think about a photograph. These days an image is so easily copied and shared that its status as an object is often dismissed.”

There are also satisfying parallels, said Kolster, between the wet plate process and the subject being photographed, the LA River. “For a start, I’m photographing a wet subject using a wet process.” He also loves the flaws in these ambrotypes. The chemistry of wet plate photography is primarily sensitive to ultraviolet light, which is invisible. As a result, I can never really predict what a plate will look like when I use the process,” he said, “which I love because it helps me see my subject in new ways.”