A Century Gone: The Medical School of Maine

By Mary Pols

When Jewett wasn’t teaching, he was covering many country miles around Berwick in his carriage, tending to his own patients. His daughter, Sarah Orne Jewett, seventeen at the time of this speech and already working on the stories that would make her one of Maine’s most famous women, had been going on rounds with him since she was a child. She was two years away from publishing her first story in The Atlantic (and a few decades away from becoming the first woman to receive an honorary degree from Bowdoin). Her book A Country Doctor, a fictional tribute to the father she adored, was still just a seed in her fertile imagination.

The February speech had the tone of both a scolding and a rousing pep talk for students of Maine’s first medical school and the nation’s eleventh. A doctor’s studies cannot end after the medical degree is conferred, Jewett said, but often they do. “No class of educated men is so characterized by such neglect of regular, progressive improvement, as physicians,” Jewett told the class, which in that era had only two sixteen-week terms to go before they’d receive a medical degree.

Interior view of the College commons (now the carpentry shop) chemistry lab, which would have been used by Medical School students, 1879.

“You must be live men,” Jewett said to the group, which would have included about eighty new students. “Thinking, studious, reflecting men, never prescribing for a name, never wedding yourself to routine.”

Jewett had a unique perspective. He was a Bowdoin graduate, a member of the Class of 1834. He’d arrived at Bowdoin not even a decade after the first class of twenty-one students had entered the medical school for a degree course that then only took twenty-four weeks to complete. He’d been there at the beginning, and now, at the school’s halfway mark, he was pushing for greatness. The school was designed to help fulfill Maine’s potential, and Jewett was committed to that.

Statehood was integral to the establishment of the medical school. Maine was established as a state of its own, distinct from Massachusetts, in March of 1820, and by June, its first legislature had funded the medical school in Brunswick, adjacent to—and sharing buildings and faculty with—Bowdoin, then the state’s only college. The legislature was signaling its intention to show how this new state was invested in a future in keeping with the sweeping changes of the Industrial Revolution.

The legislature granted the school $1,500 for its startup costs (“books, plates, preparations and other apparatus”), with an additional $1,000 annually. The first lecture at the new school was given the next spring by Dr. Nathan Smith, the founder of Dartmouth Medical School, who led the Medical School of Maine until 1825. Smith had been asked to take the job by Reverend William Allen, Bowdoin’s second president. In writing to accept the offer, Smith was all in for the opportunity in a new state “where neither habit nor parties have laid ruthless hand on the public institutions and where the minds of men are free from their poisoning influence, everything is to be hoped for.”

No college degree was required to enter. Indeed, a survey of doctors in Maine in 1820 found that seventy-four of the so-called doctors in the state had no college or medical degree at all. When Jewett was an undergraduate at Bowdoin, his classmates looked down upon the medical students because of these minimal standards, a clash that would continue through the school’s history. (The older medical students, prone to partying, were apparently also considered a poor influence. Pranks flowed between the two groups.) Jewett himself had left the state to get his medical degree at an even newer school, Jefferson Medical School in Philadelphia.

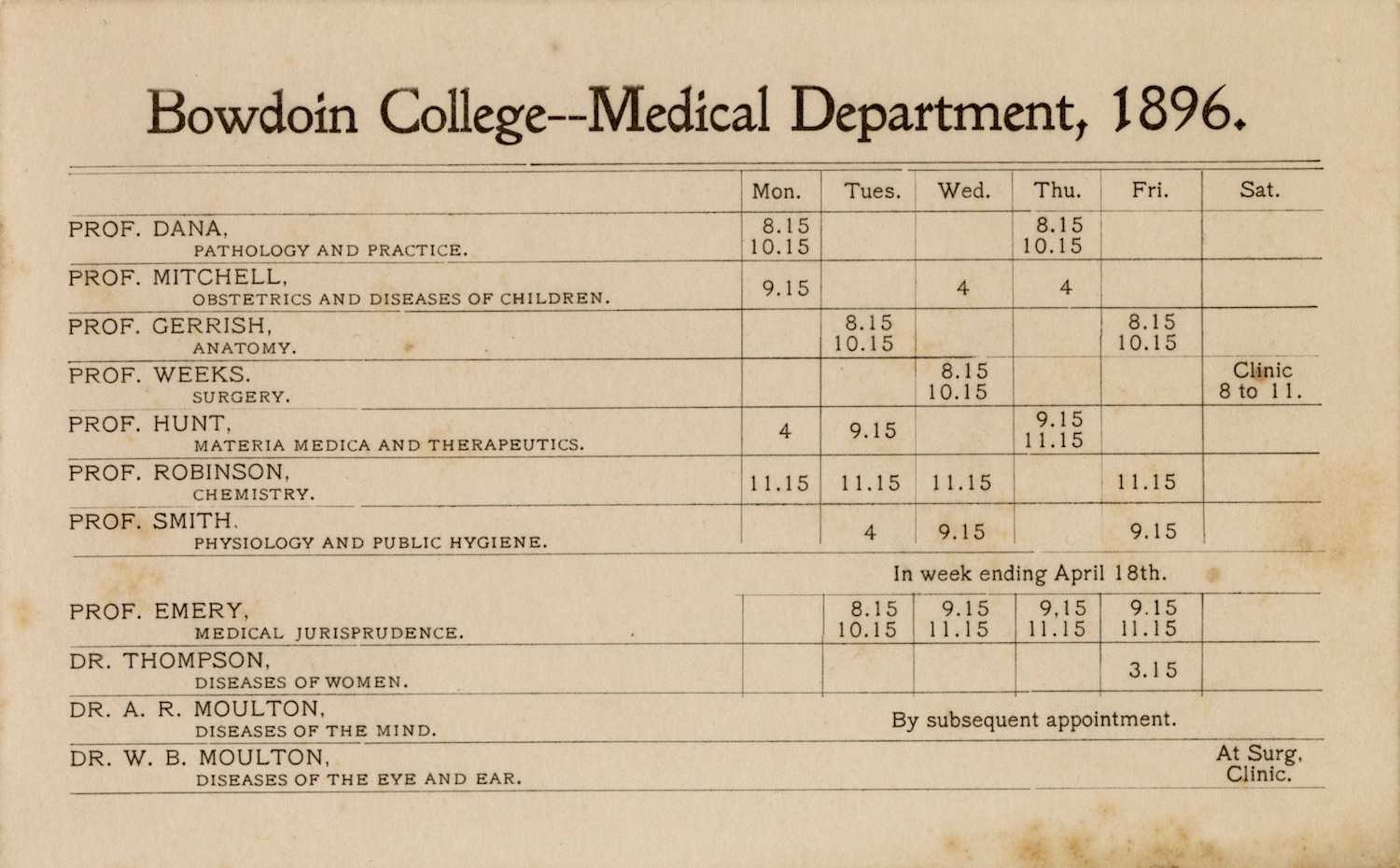

Medical School of Maine Class of 1907.

But Jewett, whose daughter’s biographers describe as just as attentive to his patients’ emotional well-being as he was to their physical needs, must have made an impression on the Class of 1867. They asked that his speech be printed, and two years later it was, in a pamphlet that can be found among other Medical School of Maine papers at the George J. Mitchell Department of Special Collections & Archives at the Bowdoin library.

When Jewett died in 1878, at sixty-three, the Medical School of Maine was on an upward trajectory, adding new chairs (physiology in 1872 and public hygiene in 1875). Maine had a new hospital by 1874, Maine General Hospital—where Jewett was a consulting surgeon—which would eventually become Maine Medical Center. The level of scholarship Jewett was calling for at the Medical School of Maine was increasing. Coursework was added steadily in each new decade, until 1904, when students devoted nearly three years to earning their degrees.

But, as Maine celebrates its bicentennial, the Medical School of Maine marks a less festive date, the centennial of its closure. Special Collections & Archives is preparing an exhibition for this fall that traces its legacy. The history is rich, says Marieke Van Der Steenhoven, special collections education and outreach librarian. Current students hear about the lore of the cadaver hook that still hangs at the top of the stairwell in Adams Hall, where the medical students would haul up bodies to dissect. In Special Collections, they can see a full coffin lid—discovered as part of the subfloor during the 2007 renovation of Adams—left over from these purchased cadavers (as well as “a fragment that actually has the receipt of where the body was coming from,” Van Der Steenhoven says).

Some classes today, especially those within the Health, Culture, and Society Initiative, are already using medical school records, such as the hundreds of theses produced by the medical school students, in class projects.

Adams Hall, shown with the Old Grandstand circa 1900, housed the Medical School of Maine.

Professor Meghan Roberts’s The History of the Body class—which focuses on historic novels, namely Mary Shelley’s Frankenstein and Hilary Mantel’s The Giant, O’Brien, as a lens through which to look at the history of the body—recently used the records to better understand what medical students of Frankenstein’s era were like.

“So, we pulled from theses in these collections,” Van Der Steenhoven said. “They’re handwritten. They are twelve pages long, and the subjects are really far-ranging. And you can see it sparking this interest. That ‘Wow, is this all it took to be a doctor? Three months and all you had to write is this final paper?’”

As Van Der Steenhoven plans the exhibit, she’s thinking not just about history but “also, pulling it forward, to how these students are engaging with these collections now.” Some might be recoiling in horror from the photographs of Medical School of Maine students cavalierly posing with “their” cadavers. Other Bowdoin students preparing for a career in medicine (8 percent of Bowdoin graduates go on to medical school) might want to learn what a doctor’s life looked like in the nineteenth century. They could spend some time with the day books of Dr. John Dunlap Lincoln, a member of Bowdoin’s Class of 1843, who went on to get his degree from the Medical School of Maine in 1846.

“Dr. John,” as he was known, practiced out of his house in downtown Brunswick. Described after his death in 1877 by the Boston Transcript as “the personification of gentle strength,” Lincoln kept meticulous records of his house and office calls from 1850 until just a few months before his death, when he closed his office for good and took to his bed. He had noted patient visits with a veritable who’s who of Brunswick history—the Merrymans, Stanwoods, Furbishes, and Skolfields, and some known only by basic identifiers such as the “Irish boy” (who lost three fingers to a hay cutter on July 17, 1850).

A tonsil guillotine used at the Medical School of Maine. Tonsillectomy by guillotine was a popular treatment for throat infections in the late 1800s.

Like Jewett, Dr. John taught at the Medical School of Maine. And like him, perhaps, he envisioned the school only gaining in reputation and size in the ensuing decades and next century. It had long catered primarily to Maine residents; up to 86 percent of its graduates were from the state, and many, if not most, of them remained in the state to practice. But three things interfered with that hope for longevity: first, its financial situation; second, the lack of a hospital in Brunswick (Maine General in Portland was the nearest); and finally, and perhaps most important, a visit in 1909 from a man named Abraham Flexner.

Money problems had long plagued the school. The Maine legislature, having promised the annual stipend of $1,000 to the medical school, stopped those payments in 1834. The school depended on tuition for its operating budget. There were gifts from alumni. The Garcelon and Merritt Fund, which continues today to provide scholarships to medical school for Bowdoin graduates and Maine residents, was established with a $400,000 endowment by Catherine Garcelon on her death in 1891. Garcelon, whose husband and brother were both graduates of the Medical School of Maine, made the bequest in her will, but it was tied up in court for six years.

As the nineteenth century began to draw to a close, pressure was growing to pair the students with clinical opportunities they simply couldn’t get in Brunswick. The Portland School for Medical Instruction had opened and was operating in association with the Maine General Hospital. Brunswick students traveled there for practical experience. Meanwhile, there were advocates at Bowdoin who wanted to maintain the Medical School of Maine in Brunswick, including the College’s seventh president, William DeWitt Hyde, and a professor, Dr. Frank Nathaniel Whittier. They might have prevailed if it hadn’t been for Flexner and his infamous report of 1910, which ultimately established the standards for the modern medical school.

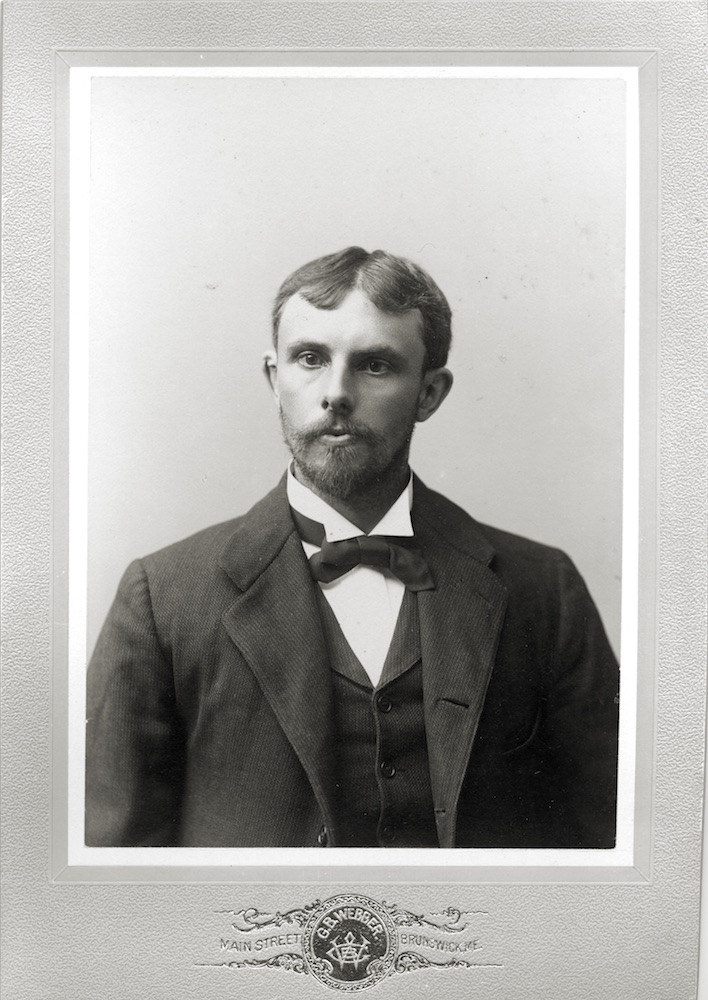

Frank Nathaniel Whittier, Class of 1885, was an advocate for the Medical School of Maine at a time when enrollment was dwindling and it was in financial decline.

A Kentucky native, Flexner was the author of The American College: A Criticism, published in 1908. He’d studied classics at Johns Hopkins University, finishing his degree in just two years, and had done some graduate work at Harvard and the University of Berlin before founding a college preparatory school in Louisville. It was this work that inspired his critique. That caught the attention of the new Carnegie Foundation, which asked him to do an assessment of medical schools in North America. The foundation’s goal was to protect the general public from poorly trained physicians, and also to make sure that unwitting students weren’t led astray by what the head of the Carnegie Foundation, Henry Smith Pritchett, called “the prey of commercial advertising.”

Flexner quickly made his way around the United States and Canada, visiting 155 medical schools. His subsequent report, published in 1910, recommended that the vast majority of them be shut down. He believed that the United States was producing far too many doctors, and of low quality. In Maine at the time of his visit, eighty-one potential doctors were enrolled and the staff was thirty-five. The state’s population was 724,508, and there were 1,198 physicians. The medical school’s dissecting room, Flexner noted, was supervised not by any of its fourteen professors but by recent graduates. Clinical instruction was by this point given at the Portland School for Medical Instruction, but that, with its “wretched dispensary,” did not pass muster with Flexner.

Medical School of Maine Class of 1869 with various medical instruments.

“Neither end of this school meets the requirements for the teaching of modern medicine,” Flexner wrote. Considering what he said about other schools, that criticism was relatively benign. Flint Medical School, a medical school affiliated with Tulane, was a “hopeless affair,” Flexner wrote. . . “on which money and energy alike are wasted.”

He recommended closing the schools at Bowdoin, Dartmouth, and Vermont. “There is no good reason why these institutions—colleges all of them—should be concerned with medicine at all,” he wrote. How many schools closed as a direct result of Flexner’s report is debatable since some were already in financial decline, including the Medical School of Maine, but within the next decade, about 75 percent of those medical schools he’d visited were shuttered. At the time of Flexner’s visit, the Medical School of Maine was bringing in $8,100 in fees annually, but losing about $7,000 annually, and that was before World War I drastically reduced the number enrolled (in 1916 and 1917, each graduating class was only 10 students).

Fierce advocates for the Medical School of Maine remained, despite the deflating report and subsequent news in 1920 that the Council for American Medical Education would soon strip the school of its Class A rating unless it updated its equipment and labs and spent $75,000 annually. Once again, the strongest advocate was Dr. Whittier, Bowdoin Class of 1885 and an 1889 graduate of the Medical School of Maine. The College’s first athletic director (the football field was named in his honor), Whittier was professor of pathology and bacteriology, as well as Bowdoin’s doctor.

Whittier believed the school could be run without the $75,000 annual expenses as proposed. He continued to make that argument until president Kenneth C. M. Sills announced in the fall of 1920 that the school would close in the spring of 2021. Whittier died in December 1924, after a heart attack on the train between Brunswick and Portland. His death was front-page news in the local papers. Whittier was a noted criminologist, credited with being the first to develop a method of distinguishing between animal and human blood at a crime scene. He served in the medical corps in World War I and became the medical examiner in Cumberland County.

In all, the Medical School of Maine produced 2,138 graduates in its century in existence, men who fanned out across the young state and beyond, some becoming country doctors like Theodore Herman Jewett and John Dunlap Lincoln, with others going on to earn additional degrees, to practice in big cities, or to go into teaching. Likely, none were as devoted to the Medical School of Maine as Whittier. Speaking at his memorial service, Sills described the Farmington native as being, from 1897 until the school’s closing, “in a very real sense the heart of the institution,” working “indefatigably” on its behalf. Whittier was only a child in 1867 when Jewett delivered his inspiring speech to the incoming class, but he lived its ideals as a thinking, studious, reflective man. Sills noted in his eulogy that Whittier’s laboratory lights could be counted on to still be burning brightly when the rest of the campus was asleep. Both an academic and an entrepreneur, Whittier aimed to make an impact on the larger world. He saw potential in the Medical School of Maine, even at its end.

This story first appeared in the Winter 2020 issue of Bowdoin Magazine. Manage your subscription and see other stories from the magazine on the Bowdoin Magazine website.