Understanding Maine’s Statehood

By Tom Porter

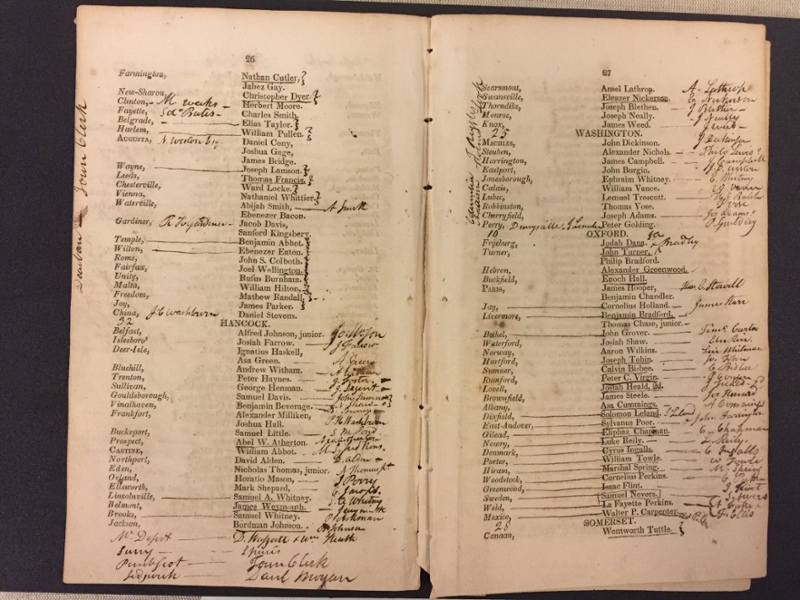

It’s a draft copy of the Maine constitution from 1819, explained Marieke Van Der Steenhoven, education and outreach librarian at Bowdoin Library’s George J. Mitchell Department of Special Collections & Archives. It dates from the constitutional convention of that year, when representatives gathered to discuss how the new state of Maine would look. This particular copy includes a heavily annotated list of the 236 delegates, marking who turned up and which of them were replaced by others.

“Many of these delegates had Bowdoin connections,” said Van Der Steenhoven, “such as College trustees John Chandler and William Preble, who was also an honorary degree recipient.” Overseer and trustee William King, meanwhile, chaired the convention, while another of the delegates was Stephen Longfellow, father of the poet Henry Wadsworth Longfellow, Class of 1825.

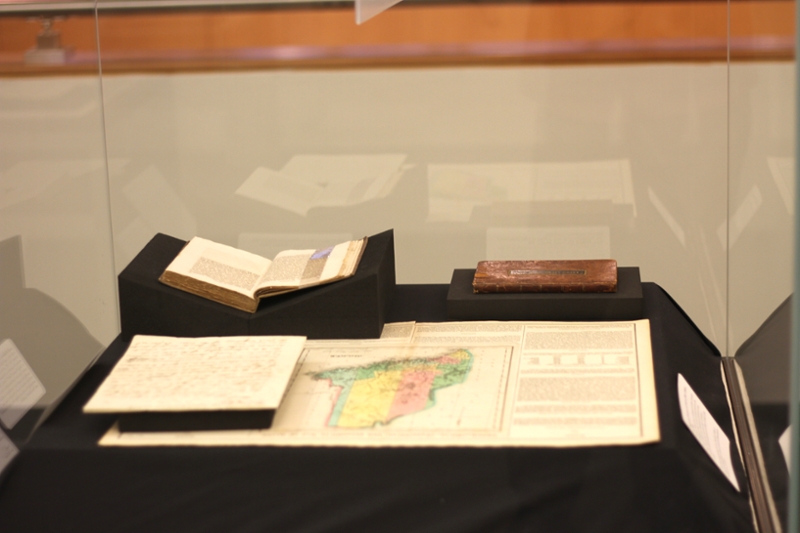

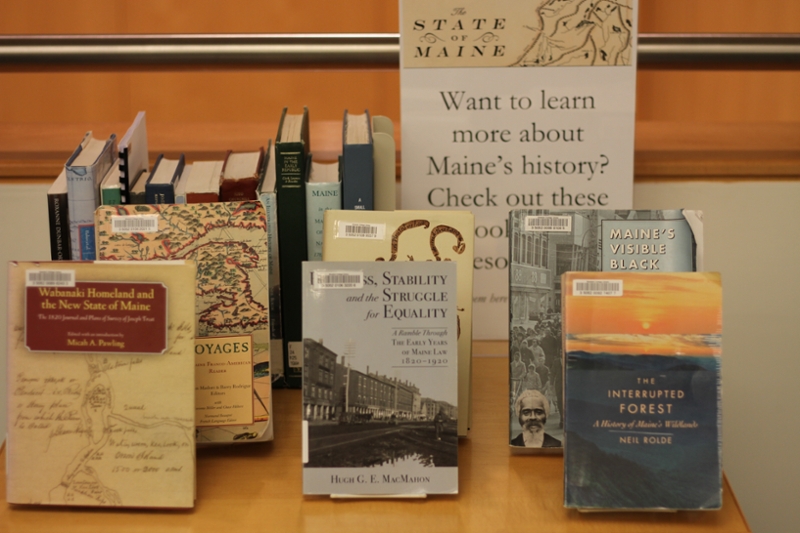

The document is one of dozens on display this semester in the State of Maine exhibition on the second floor of the Hawthorne-Longfellow Library. Maine’s complicated road to statehood culminated on March 15, 1820, when the district separated from Massachusetts and was accepted as the twenty-third state in the Union. Van Der Steenhoven curated the exhibition, which uses rare books, political tracts, maps, and other materials to explore the unexpected and familiar narratives that led to statehood, and considers Bowdoin’s unique role in that journey.

The Natural Resources and People of Maine

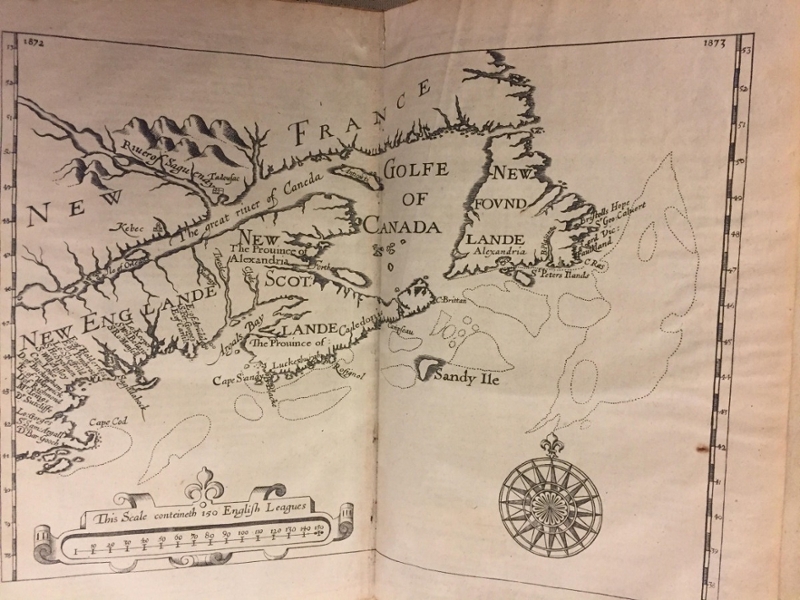

The exhibit comprises materials arranged thematically by display case, with one dedicated to Maine’s natural resources, climate, and people, explained Van Der Steenhoven. “The materials in Bowdoin’s historic collections routinely reflect dominant perspectives due to historic collecting practices. Finding the voices of indigenous folks, people of color, or women can often prove challenging within our collections.” It is the work of scholars, librarians, and archivists to build representative collections and to read through the absences to build a broader understanding of our history. Using Samuel Purchas’s 1625 map of New England to discuss the erasure of the Mawooshen tribe of the Wabanaki people, or Joseph Whipple’s 1816 problematic characterization of women to discuss how statehood impacted white, African American, and Native American women, are just two of the ways to read across these historical texts.

In Benjamin Lincoln’s description of the District of Maine from circa 1793, the natural resources of the area are considered, primarily to encourage trade between Massachusetts and the West Indies. However, this documentation of the eighteenth-century climate can also help us better understand climate change. The Maine weather during the pre-separation era was typically more severe than now. The statewide average temperature was 3.2 degrees colder and growing seasons were two to three weeks shorter.

Separation Anxiety

While indigenous people have resided in areas across this region for centuries, the first European settlers colonized Maine in the early seventeenth century and the district was gradually appropriated by Massachusetts beginning in 1651. “This section of the exhibit looks at the issue of Maine’s separation from Massachusetts” Van Der Steenhoven said. “Prior to the formal act of separation in 1819, there were at least six previous votes on the issue dating from 1792 (and even earlier attempts dating to the early 1700s). The pamphlets on display feature the passionate addresses made by separationists to the people of Maine.” The campaign for separation was complicated and allegiances shifted over time, explained Van Der Steenhoven. Reflected in the exhibition is the tension between those settlers in the interior of the state and the coastal merchant class, who opposed it, fearing statehood would add to their tax burden by introducing another domestic border and more tariffs.

Another section looks at the establishment of Maine as a state, its constitution, and the Missouri Compromise—the legislation that admitted Maine into the Union as a free state, while simultaneously admitting Missouri as a slaveholding one. Though slavery was abolished in Massachusetts (and thus the District of Maine) in 1793, it’s an unfortunate reality that the foundation of statehood is inextricably tied to the growth of slavery in the US, said Van Der Steenhoven. This national debate over slavery and Maine’s statehood is represented in the exhibit through a variety of published addresses made on the floor of the US House and Senate.

A Bloodless War

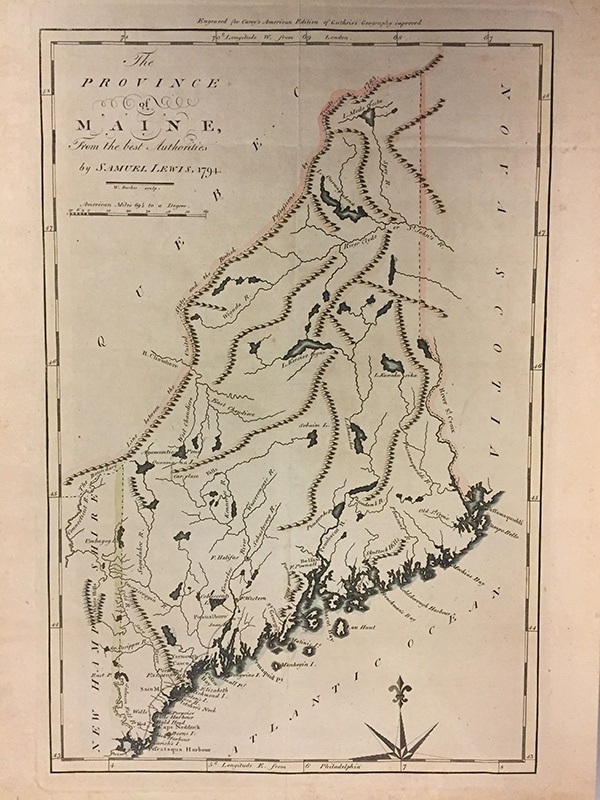

Moving later into the nineteenth century, an area of the exhibit looks at the changing shape of Maine. In 1820, Maine was geographically smaller than it is today, explained Van Der Steenhoven. The Pine Tree State’s first few decades were wrapped up in the Northeast Boundary dispute, which took issue with the vague border description outlined in the Treaty of Paris between the US and the British territory that is now Canada.

The issue was resolved by a peaceful compromise, the Webster–Ashburton Treaty in 1842, following the Aroostook War, which involved no actual fighting. It was then that the state took the shape we are familiar with today. “It was an important moment in Maine history—the state (and country) was allocated 9,000 square miles of more territory.” The library has no shortage of maps, letters, and original government documents on this issue, said Van Der Steenhoven. “If we had the space, we could do a whole exhibit on this topic alone.”

The Bowdoin Connection

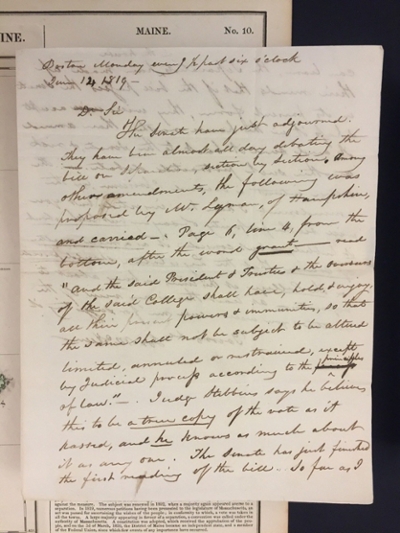

Finally, the centerpiece of this bicentennial exhibit examines Bowdoin’s connection to statehood. Because Bowdoin was established by the Massachusetts legislature in 1794, she said, there was some concern about separation. In a June 14, 1819, handwritten letter to College Overseer Charles S. Daveis, son of former college president and also an overseer, Joseph McKeen, Jr., recounts—just four days before Massachusetts governor John Brooks signed the Maine’s separation bill—that debate over separation remains friendly to the College. Also featured is the inaugural address from College President William Allen, who was at Bowdoin’s helm from 1820 to 1839. “He talks about the ‘momentous occasion’ of statehood, positioning Bowdoin as being the ‘shining northern light’ in the education of young geniuses.”

The Bowdoin Library has a wealth of resources to help people better understand Maine’s history from a variety of perspectives, said Van Der Steenhoven. “The Library’s exhibit program looks to highlight the incredible collections,” she added, “to pique people’s interest in a particular subject that we have strength in. For every document on view, you can dig much deeper into our collections and experience history firsthand.”