New Class Examines the Contributions of Black Women to US Intellectual History

By Tom Porter. Photography by Fred J. FieldWhat do Phillis Wheatley, Sojourner Truth, and Ida B. Wells have in common? They lived in different eras and different regions and they never knew each other, but they all come together in a new collaborative pair of courses looking at the words and experiences of black women in US history.

What does bringing these women together in conversation do? How have their differences and similarities changed the course of American history? These are some of the questions being tackled.

Black Women’s Lives as the History of Africana Studies is being co-taught by Associate Professor of Africana Studies Judith Casselberry and Tess Chakkalakal, who is the Peter M. Small Associate Professor of Africana Studies and English and also director of the Africana Studies Program. The fall semester examined authors from the eighteenth and nineteenth century, such as the ones mentioned above. In the spring there will be a second class, studying women from the twentieth and twenty-first centuries and introducing students to works by Zora Neale Hurston, Rosa Parks, Lorraine Hansberry, Condoleeza Rice, and Angela Davis.

Established in conjunction with the fiftieth anniversary of Africana studies at Bowdoin, the courses address the diversity of black social and political thought by black women that has too often been viewed as monolithic and peripheral to mainstream studies of American culture.

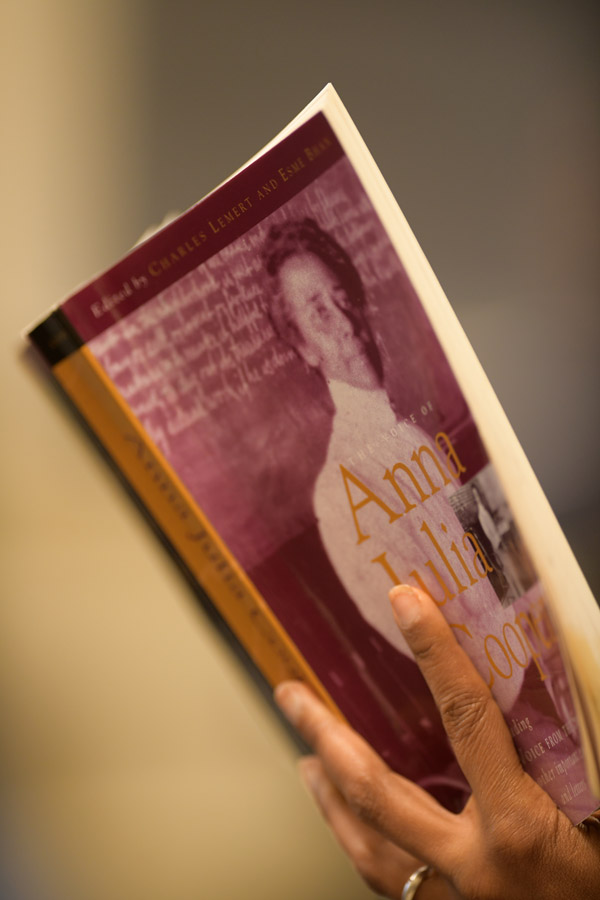

In one recent class, they discussed the writings of celebrated educator and activist Anna Julia Cooper, who died in 1964 at the age of 105. The passage that was being examined included the phrase “not till race, color, sex, and condition are seen as accidents, and not the substance of life,” which prompted a lively conversation on Cooper’s politics, which have become foundational to black feminist thought. Students were surprised by Cooper’s viewpoints that seemed socially conservative by today’s standards. When Cooper was writing in the late-nineteenth century, however, her views would have been seen as radical, say the professors.

“This class is one of my favorite classes I've taken at Bowdoin so far,” says Safiya Osei ’21. “To learn about so many black women who have carved out a space for themselves in a society that did not value their work, and to debate the importance of this work in both a historical and a more contemporary context, has been the biggest takeaway I've gotten out of this class.”

Kevin Fleshman ’23 says he was drawn to the class after being introduced to Professor Casselberry over the summer through the Geoffrey Canada Scholars program. “I really enjoyed her teaching style and energy,” he said. He was also impressed by Professor Chakkalakal’s enthusiasm for the Black Women’s Lives course, which he said was contagious.

The main thing he learned, said Fleshman, was how to engage in highly intellectual classroom discussions. “As a first year, I feared my perspective on things would either be inferior or not valid enough to add to the discussion. However, Professor Chakkalakal’s motivation throughout the year has pushed me to participate in discussions in all of my classes.”

“One of the main aims of the class is to introduce students to a new narrative/canon of Africana studies that places the words and experiences of black women at its center,” says Chakkalakal. “Co-teaching with Judith has been one of the most rewarding experiences of my teaching career,” she adds. “The class is focused on creativity and collaboration. It is what we do together that makes for a learning environment that engages all students regardless of their different life and learning experiences.”

These sentiments are echoed by Casselberry: “The way we went about teaching spoke to the goals of the course—to bring students into a truly interdisciplinary intellectual environment, as they grapple with key issues and themes in Africana studies through the lives of black women.” The idea for the course evolved organically, she explains, through a conversation she had with Chakkalakal. “As an anthropologist, having a conversation with Tess, a literary critic, allowed us both to see these texts through the different disciplinary expertise of one another. One of our favorite things about teaching this class was how much we learned about ourselves by talking about these black women together.”