Socialism: No Longer a Dirty Word?

By Tom PorterDuring the Cold War, the term “socialism” for many Americans was synonymous with “communism,” which meant the Soviet Union, a.k.a. the enemy. Today, things are different, explains Samuel Arnold ’01, associate professor of political science at Texas Christian University.

Arnold, who majored in philosophy, visited campus in early November to deliver a talk called “Socialism for Centrists: A Political Philosophy for the 99 Percent.” Revived in recent years by high-profile politicians like Bernie Sanders and Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez, he observed, the concept has gone mainstream. But what is socialism and what does it mean to the average person? Before delivering his lecture, Arnold took time to answer some questions.

***********************

Socialism is…?

In essence, it means social ownership of the means of production, whereas capitalism means private ownership of them. There are all sorts of socialism—some allow for profits and markets, and others involve planning, whether central planning like in the Soviet Union, or some kind of democratic planning. But whether the economy uses markets or planning, the key feature of socialism is social ownership of the means of production.

Why did the “S word” have such have negative connotations for so many years?

The Cold War was a big part of it. The generations of Americans who grew up at that time often equate socialism with Soviet-style communism. Newer generations, however, don’t have those associations. Some see capitalism as representing rampant inequality, and the socialist alternative sounds appealing.

The political right in the US has successfully branded any redistributive program as socialist, and many young people are like “well, I kind of like some redistribution, so I guess I’m a socialist.” So, in some ways the right has helped socialists by defining what socialism is: If it simply means government intervention to help ordinary people, that sounds OK to many.

What is the philosophical argument for socialism?

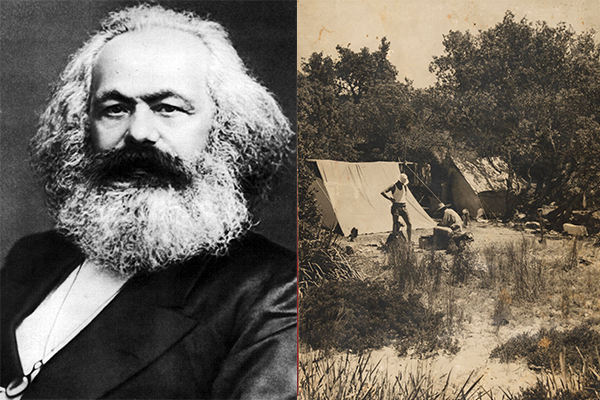

In my talk, citing the work of the great political philosopher GA Cohen, I draw an analogy with a camping trip. Imagine how you would behave, and how you would like people to behave, on a camping trip. You sure as hell don’t behave like a capitalist, you don’t assert your private property rights or try to barter or bargain. Instead, if you need help putting up a tent, you just ask for help and get it, just as you would help someone else needing it. If you asked a capitalist for help putting your tent up on a camping trip, he would likely say “what’s in it for me?”

Cohen takes this argument not to show that socialism would work in society at large—there’s no indication here that it would be effective in a wider context—but to show that, in a limited context like a camping trip, it’s a really attractive philosophy.

What’s important about this argument is that it shows that a certain “nonmarket” kind of socialism has something really attractive about it. Wouldn’t it be great if we could somehow figure out how to make the whole economy work like a camping trip—that is to say, if we had a norm of communal reciprocity, where people help each other for the good of society?

What about the argument that socialism stifles private enterprise and quashes the individual?

The argument I make here is really a philosophical point about desirability, so it doesn’t address that particular issue. However, even the most conservative capitalist would probably find socialism desirable on a camping trip. The challenge is then to make socialism work beyond camping trips.

It’s removed from reality, I know, but if socialists can wrest that important philosophical concession from capitalists, it’s a major step forward for them. I also like to stress that socialists should not demonize capitalists as people, which often happens. The critique of capitalism is about its structure, not the people behind it.

What about democracy and the freedom to choose?

The second part of my talk is about democracy. I argue that capitalism undermines democracy by giving one class—the business class—great power because they control means of production and therefore have tremendous leverage. They can threaten the government with capital flight whenever they want—for example, if Bernie Sanders was elected president! So, in a capitalist democracy you can’t do anything big that capitalists don’t like.

"Some see capitalism as representing rampant inequality, and the socialist alternative sounds appealing."

But hasn’t the alternative—a state-controlled economy—also been shown not to work?

Total state control of the economy through state bureaucrats is known as “statism.” This is what we saw in Soviet Russia, where ultimately it didn’t appear to work that well. It’s also what we see today in China, where capitalism and communism have been combined without democracy.

There is a form of democratic socialism, however, called market socialism, developed by the philosopher and mathematician David Schweickart, among others. This takes very seriously the problems of central planning and tries to blend the best elements of socialism and capitalism by having profit-seeking firms owned by workers, responding to market demand. Investment funds will also be socially controlled, i.e., not through private banks. This makes the idea of social ownership of the means of production tangible and real.

What examples are there of this model working?

Workplace democracy exists for sure. There are lots of worker-owned firms, some in the US, but especially in Spain, where there’s a big network of worker cooperatives called Mondragon Corporation, employing over 70 thousand people. Regarding the social control of investment banks, there are some state-controlled public banks. In the US, for example, there’s the Bank of North Dakota.

Are you advocating socialism?

Not necessarily. I don’t know if socialism is, on balance, the best system, but I do think it’s worth considering. I’m prepared to admit, however, that when it gets to actual politics, things can get very messy.

Professor Samuel Arnold’s visit to Bowdoin was sponsored by the Department of Philosophy.