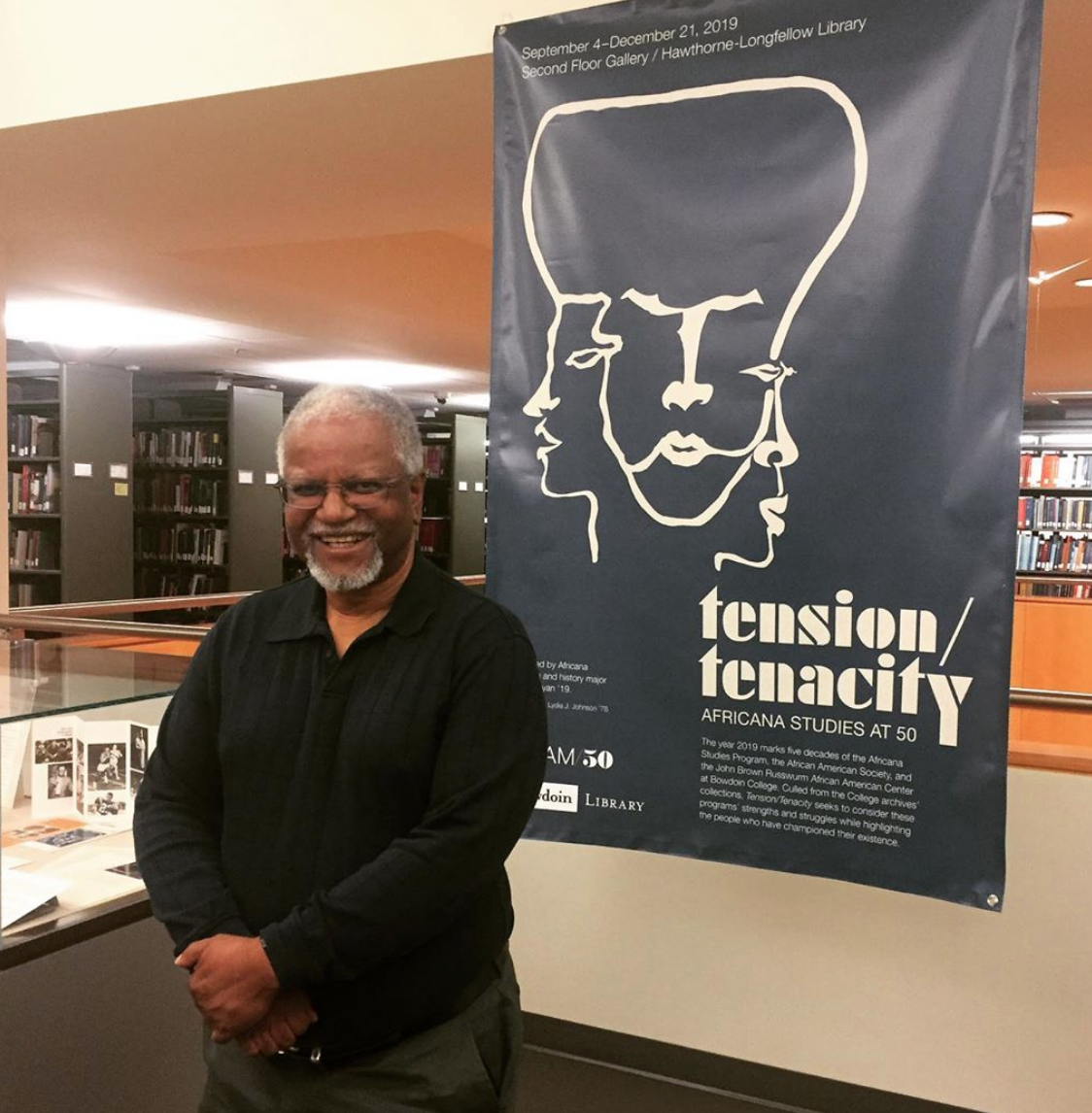

Africana Studies and Me

By Randolph Stakeman for Bowdoin Magazine

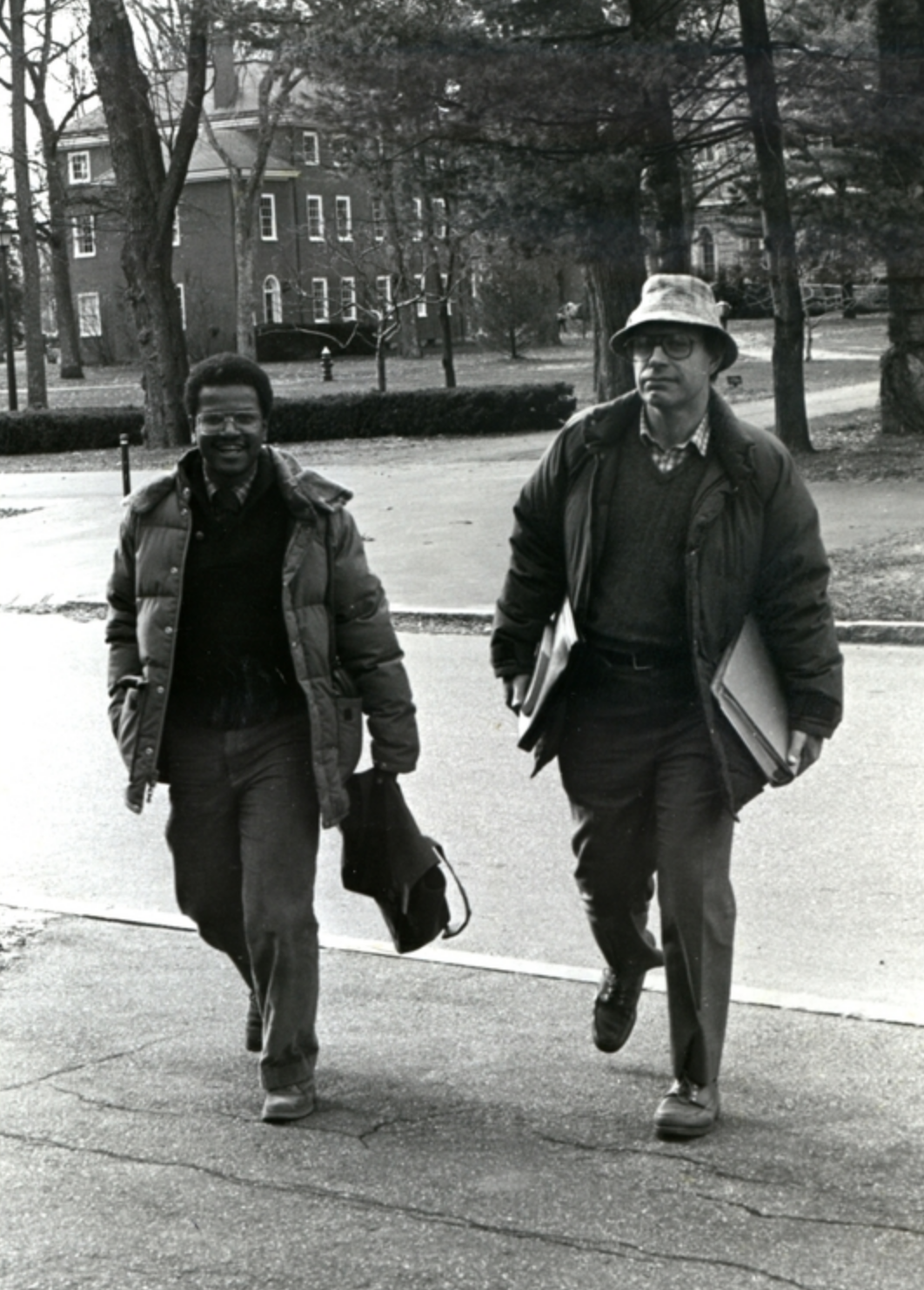

I came to Bowdoin in 1978. It was my first job after graduate school, and I hadn’t even completed my PhD dissertation. I had taught one class in my life, so I had only a vague idea of how to be a college teacher and no idea of how academic institutions worked. What I did have was an experience as a student during the 1960s at a small liberal arts college (Wesleyan University). That experience had taught me what a liberal arts college should do for a student. It should broaden one’s horizons, teach critical thinking, and lead you to challenge assumptions and unexamined truths. Armed only with those beliefs, I was “thrown into the deep end of the pool and told to learn how to swim.” I taught African history, and my courses were part of the African American Studies Program. As a student, I had demonstrated and had been part of a building takeover at Wesleyan University to get such a program started at roughly the same time as Bowdoin founded its program. I was glad to be part of the program and waived my customary first-year immunity from committee work to be on the steering committee for the program.

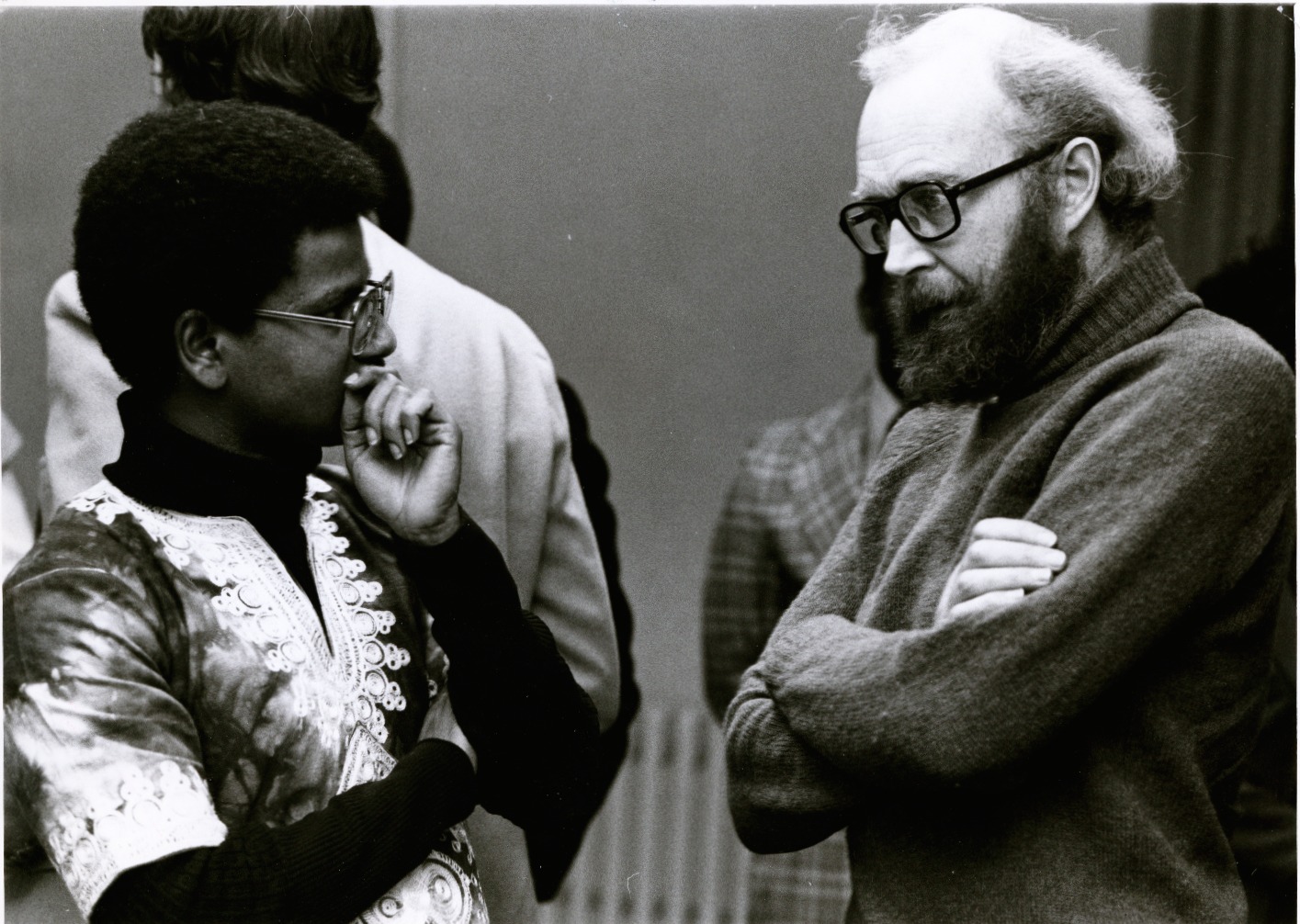

At the time, the program was directed by the charismatic John Walter, a fellow historian, who taught African American history courses. John had an interesting custom of going to Moulton Union with students after his class. He would sit down with students, sipping his tea, and continuing the class discussion or talking about current events or even Bowdoin in general, in booths and tables at the back of Moulton Union, an area he called the “back of the bus.” A teacher taking an interest in his students’ education outside the classroom was the epitome of what I thought liberal arts teaching at a small school should be. On a couple of occasions, I joined in, more as a “fly on the wall” than a participant.

John moved on in a couple of years, and I was part of the search committee to find the next director of African American studies. I had come to understand how the position worked. At its inception in 1969, the program had been “sold” to the Bowdoin faculty and administration as a program that only called for one additional position, that of director. The other courses in the program would be supplied by people already at Bowdoin. Dan Levine was already teaching African American history courses, and Craig McEwen was already teaching a sociology course on race and ethnicity. The director would be based in a department that would have the right to hire, reappoint, and ultimately make the decision to tenure or not. The search committee was composed of people from the various departments in which it was expected that one of the finalists would likely be based. After identifying finalists, the decision to hire a person was made first by a department and only secondarily by the search committee. After reading dozens of dossiers and having numerous discussions, the committee recommended Lynn Bolles to the sociology and anthropology department. They decided that she would make an excellent addition to their department, and we recommended her as the new director of African American studies.

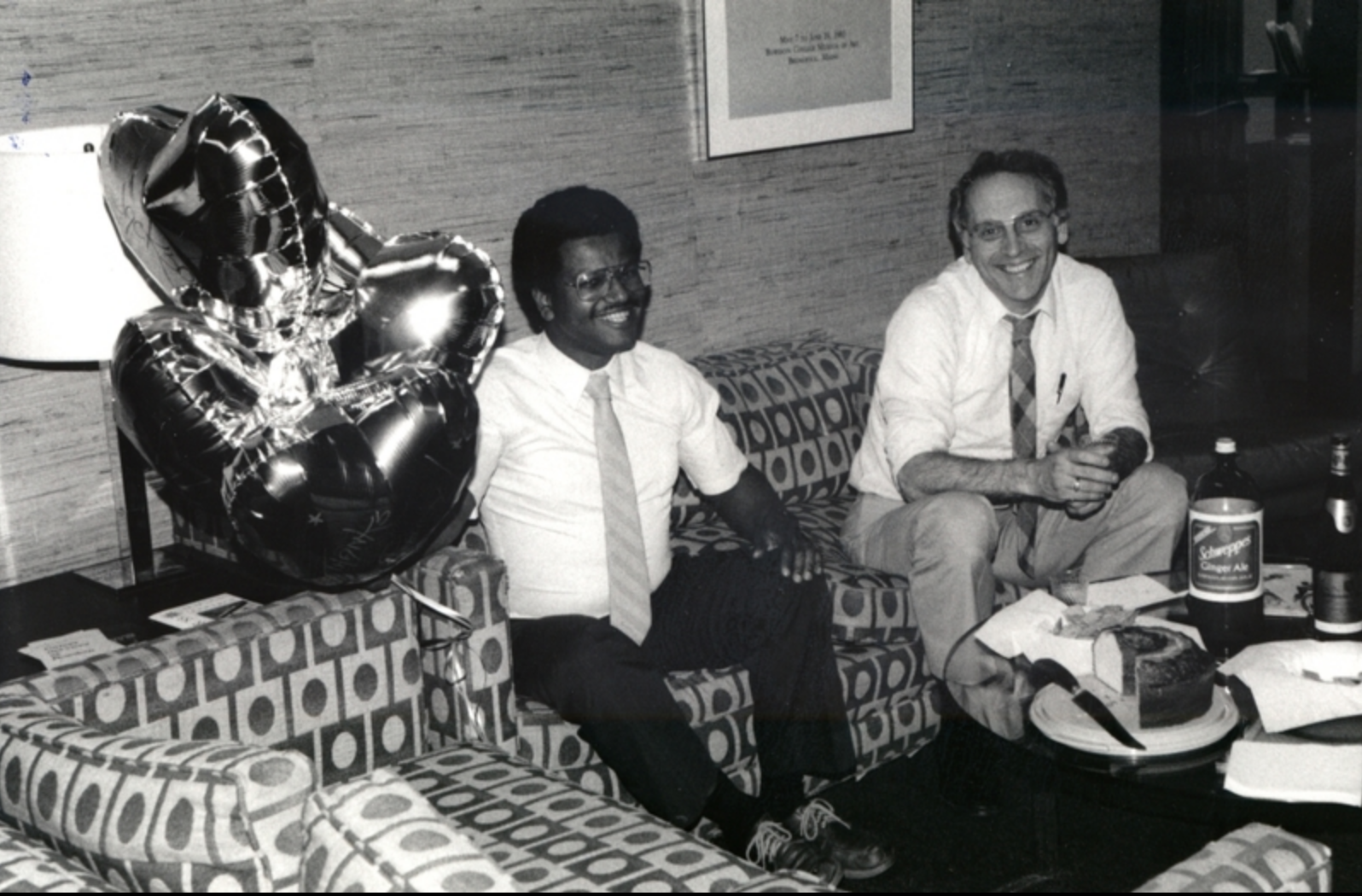

Lynn was an anthropologist whose research focused on Caribbean women. She joined us in 1981 and added an international dimension to the program, which it had been lacking before. Under Lynn and her academic coordinators—first Noma Petroff and then Harriet Richards—the program became a well-oiled machine operating much as the founders had wished. The core courses were stabilized—that is, the departments pledged to offer them every year—and new courses were added as the College hired new people. Lynn’s teaching and research were of such high quality that reappointment and eventually tenure were not issues. Lynn blazed new trails at the College and eventually became the first African American to become a tenured professor at Bowdoin.

I filled in for her one semester when she went on maternity leave to have her first son. She had contracted to have the singing group Sweet Honey in the Rock give the program’s annual John Brown Russwurm “lecture.” Neither the program nor I had ever produced a concert before, and that fell into my lap. Fortunately, Noma Petroff, the academic coordinator at the time, is a wonder, and she organized the “lecture” with the precision and attention to detail of the D-Day Normandy invasion. With student volunteers handling everything from bottled water and flowers in the dressing room to hosting duties, Bernice Regan, the leader of the group, complimented our “team” from the stage.

Lynn decided to leave in 1989 to accept a position at the University of Maryland College Park. Al Fuchs, the dean of the faculty, approached me to ask me to accept the position. The program was scheduled to be reviewed by an outside committee (as Bowdoin departments are every ten years or so), and he wanted me to shepherd it through the review process as well as to search for a new senior person to become the director. I agreed to a three-year term to helm the program through this transition.

The first stage in these departmental reviews is a self-study, which I wrote in this instance. It noted that, with Lynn Bolles’s appointment, the program had become more than the African American Studies program it was at its beginning. It had become an international program looking at how cultures derived from Africa had adapted to and related to societies all around the world. I called for a change in name to the Africana Studies program to reflect the change in the program itself. I also called for new faculty positions, the expansion of the program into new areas like religion and music, and for the program to have some say in reappointment and tenure decisions. The College accepted the name change and took the rest under advisement. While this was going on, a new president, Bob Edwards, had arrived. Al Fuchs decided to leave his post as dean of the faculty to return to teaching at the College. A new dean, Charles (Chuck) Beitz, came in to lead the faculty. After we had several discussions, he appointed me to a three-year term as associate dean of faculty affairs. I then became a dean, the director of an interdisciplinary program, and a full-time teacher. It was a busy time.

The associate dean was involved in all faculty hires, and it gave me a dual role (as well as incentive) in the hiring of a new director. Despite our best efforts, for three years we could not find a senior faculty candidate to assume the post as director. Chuck and I agreed that instead we would search for two junior people whose salary would equal that of one senior hire. I would continue to serve as director of the program, and we would “grow our own”—that is, nurture these junior people until they could become senior and become director. These people would be on what Chuck called the “torn dollar bill” model, in which the program held half of the dollar bill and offered departments the chance to add a person if they agreed to be the departmental home for that person. We also stipulated that a joint committee of people from Africana studies and the particular department would decide on hiring, reappointment, and tenure, rather than the department alone. Eventually we hired Eddie Glaude in the religion department and Lelia DeAndrade in the sociology and anthropology department. Both proved to be stellar teachers, and from the mid- to late-’90s the program was building with increased enrollments and majors.

By the end of the decade, things changed significantly. Eddie accepted a position at Princeton, where he remains to this day, as the director of their African American studies program. Lelia DeAndrade eventually left academia, and our well-laid plans to “grow our own” came to naught. By 2001, I was still director and had to rebuild the program once again. Although it was not hard to get applicants for the program, it was difficult to land the people we wanted. We made some offers to promising young scholars, but none of them were accepted. Part of the problem was that there wasn’t enough of a scholarly community in Africana studies to attract people. As with students, there is a critical mass of like-minded scholars needed to attract people. There is validation in seeing that the field you have chosen is deemed important to an institution as well as having the opportunities to formally and informally exchange ideas with colleagues.

Barry Mills began his presidency in 2001. Barry is Bowdoin Class of 1972, and he arrived at the College just when the program started. He and his peers were very interested in supporting the program when he was a student, and he maintained that interest when he became president. The program, however, was not on the top of his presidential agenda, as so many other things needed his attention. It was rolling along and while I was the director it would continue to be doing fine. Dealing with the program was not an emergency.

In 1999, we successfully applied for a grant from the Andrew W. Mellon Foundation to start three study abroad programs with Bates and Colby. Each college would be the lead administrator for one of the programs, and students from all three were eligible to attend any. Bowdoin’s program was in Cape Town, South Africa, and I was tapped to lead it. Once again, I was being drawn in many directions. I taught and resided in Cape Town in fall semester 2000 and again in spring semester 2004 to teach in the program.

While in Cape Town in 2004, I visited a museum in a small coastal community called Simon’s Town, about twenty minutes south of the city. The town had been the base for the British fleet for over two centuries. Although the Nationalist Party came to power in 1948 and instituted its policy of apartheid separating the races, Simon’s Town, as a British enclave, had been exempted. By the 1960s, the British navy withdrew from the town, and the government instituted its apartheid policy, separating the people and sending them to the racially appropriate communities the government was building. With the election of Nelson Mandela in 1994 and the end of the apartheid government, people came back to the town annually on a holiday called Heritage Day. I thought this story could best be told in film, and so I hired a film crew to film the Heritage Day festivities. Working outward from there, I developed a documentary film about the town and its journey through and beyond apartheid. Upon returning to Brunswick, I entered the resulting film in the Woods Hole Film Festival, where I was awarded the emerging documentarian award. I was bitten by the documentary bug.

I have gone into this long explanation to explain my decision to retire in 2006. At that time, the prospect of making documentary films was seductive and more attractive than a future of continuing to try futilely to rebuild the program. There was another reason too. When I returned to take up my post as director, I remember some alumni coming to visit the office. They commented how comforting it felt that things were just the same as when they were students. It was an epiphany. Harriet Richards, the academic coordinator, and I were in the same place, doing the same things as when I first took over the program in 1989. The changes that had been made were superficial or behind the scenes. The job I had taken for three years had stretched to seventeen, with no end in sight. Like Lewis Carroll’s Red Queen, it had taken all the running I could do to stay in the same spot. I realized that I was part of the problem. If I was around to make chicken salad out of the chicken poop of resources that were allocated to the program, things would continue as they had been. I therefore fell on my sword and retired to pursue my passion making documentary film while there was still something left in my tank. I was fifty-seven years old.

It was the end of an era, and it created a vacuum in the program. The history department was nice enough to arrange a retirement dinner for me, which Barry Mills attended. After the festivities, Barry came up to me and said, “Don’t worry, we are going to get this right.” He meant the rebuild of the program. My retirement had pushed it further up on his agenda. He had hired Cristle Judd as his dean of faculty affairs, and he and Cristle got to work on rebuilding the program. The first step was to convene a special committee of experts in the Africana studies field to come in and evaluate what the program needed. A member of the committee met with me, as well as other faculty, and held a public meeting about the program. A few months after they concluded their visit and submitted their report, I ran into Barry on the Bowdoin paths. I asked him how he was doing, and he replied that the special committee’s report had come in, and they had recommended that I be replaced by five people. He didn’t know how he would fund that.

Barry went out on the financial campaign trail and eventually raised the money for an endowed Africana studies chair and new faculty lines. He and Cristle gradually replaced me with five people, and a new era of the program began. Barry and Cristle should get the credit for making this happen. They boldly expanded the program during a hostile political environment when many colleges were contracting, consolidating, or even eliminating theirs. He raised the money and she masterminded the searches that brought, first, senior people like Femi Vaughan and Tess Chakkalakal, then junior people like Brian Purnell and Judith Castleberry. When Femi left Bowdoin, Tess, and then Brian, assumed the directorship, thereby fulfilling the “grow your own” strategy that we had tried so many years before.

When I look at the program today and how it has grown, I smile. I led the program in its adolescence and young adulthood, but today it is a mature adult. It has its own faculty lines and therefore control over its curriculum, the hiring, reappointment, tenure, and promotion of its faculty. It is a far cry from where it started. Yet, the principles we instilled in it are still there: the internationalism, the emphasis on student mentorship, the care for students and their education, as well as the teaching of critical thinking. Talking to today’s Africana studies majors, I see that the program is doing exactly what I had hoped a liberal arts education would do all those years ago; it is broadening horizons and leading students to challenge assumptions and unexamined truths. Bravo!

Associate Professor of History and Africana Studies Emeritus Randy Stakeman retired in 2006 after twenty-eight years at Bowdoin.