Orator, Soldier, Educator: David Alphonso Lane, Class of 1917

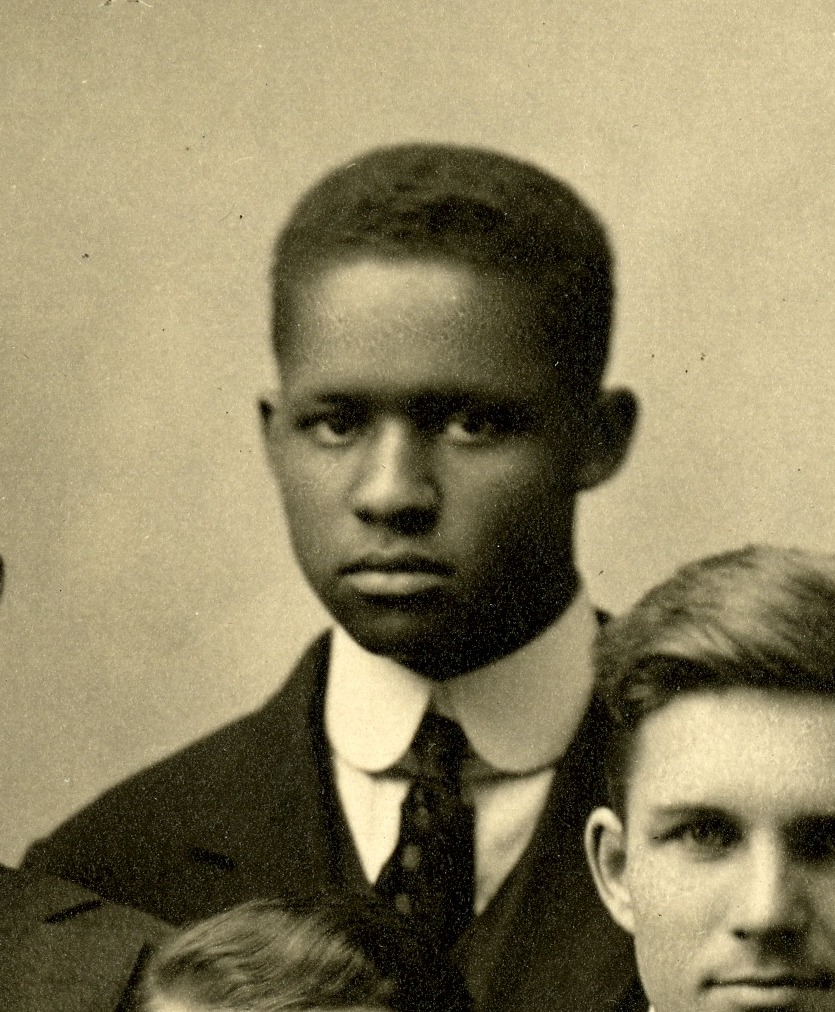

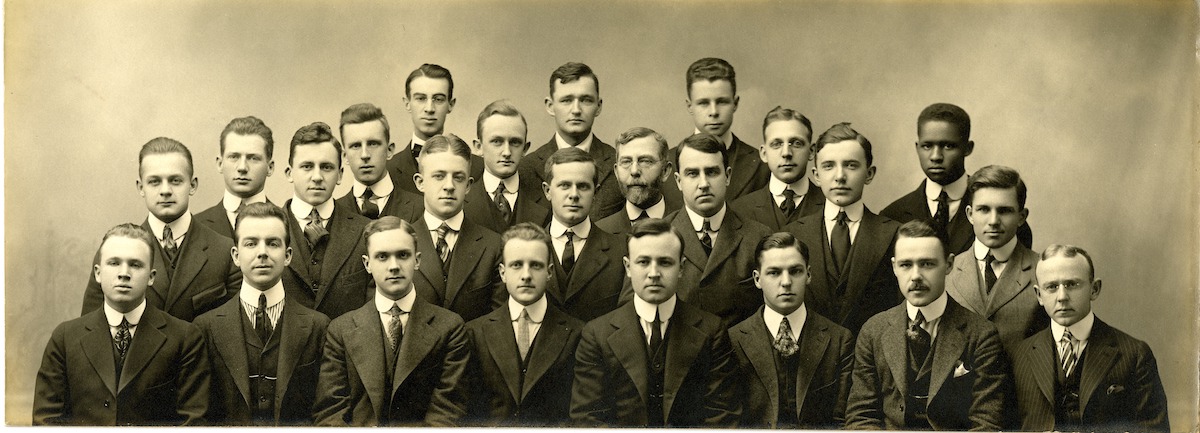

By Rebecca GoldfineThe fifth African American to graduate from Bowdoin, David Alphonso Lane Jr. (1895–1985), had a shining career as a student and a US serviceman. In between his military assignments—in both WWI and WWII—he became a leading educator and administrator for African Americans.

In his eagerness to enlist in the army, David Alphonso Lane skipped his Commencement exercises on June 21, 1917. A week before graduating, he left for training camp in Fort Des Moines, Iowa.

Lane's haste to move on after graduating had everything to do with his desire to help the war effort rather than any ill will toward Bowdoin. He remained attached to the College throughout his life, corresponding intermittently with administrators to update his address and résumé and contributing regularly to the alumni fund. He also returned to campus for his 50th Reunion in 1967, where he organized and presided over a memorial service for his classmates in the chapel.

"Debater Par Excellence"

Lane was born on October 18, 1895, in Washington, DC. He attended M Street High School, which also had Samuel Dreer as a pupil. Dreer was the second African American to earn a degree, in 1910, from Bowdoin.

Lane graduated magna cum laude from Bowdoin, one of the top ten scholars of his class of seventy-seven men and the only African American enrolled at the school at the time. A member of the academic society Phi Beta Kappa, he was also the first African American student to join the Bowdoin debate team, and he garnered several awards for public speaking and debate.

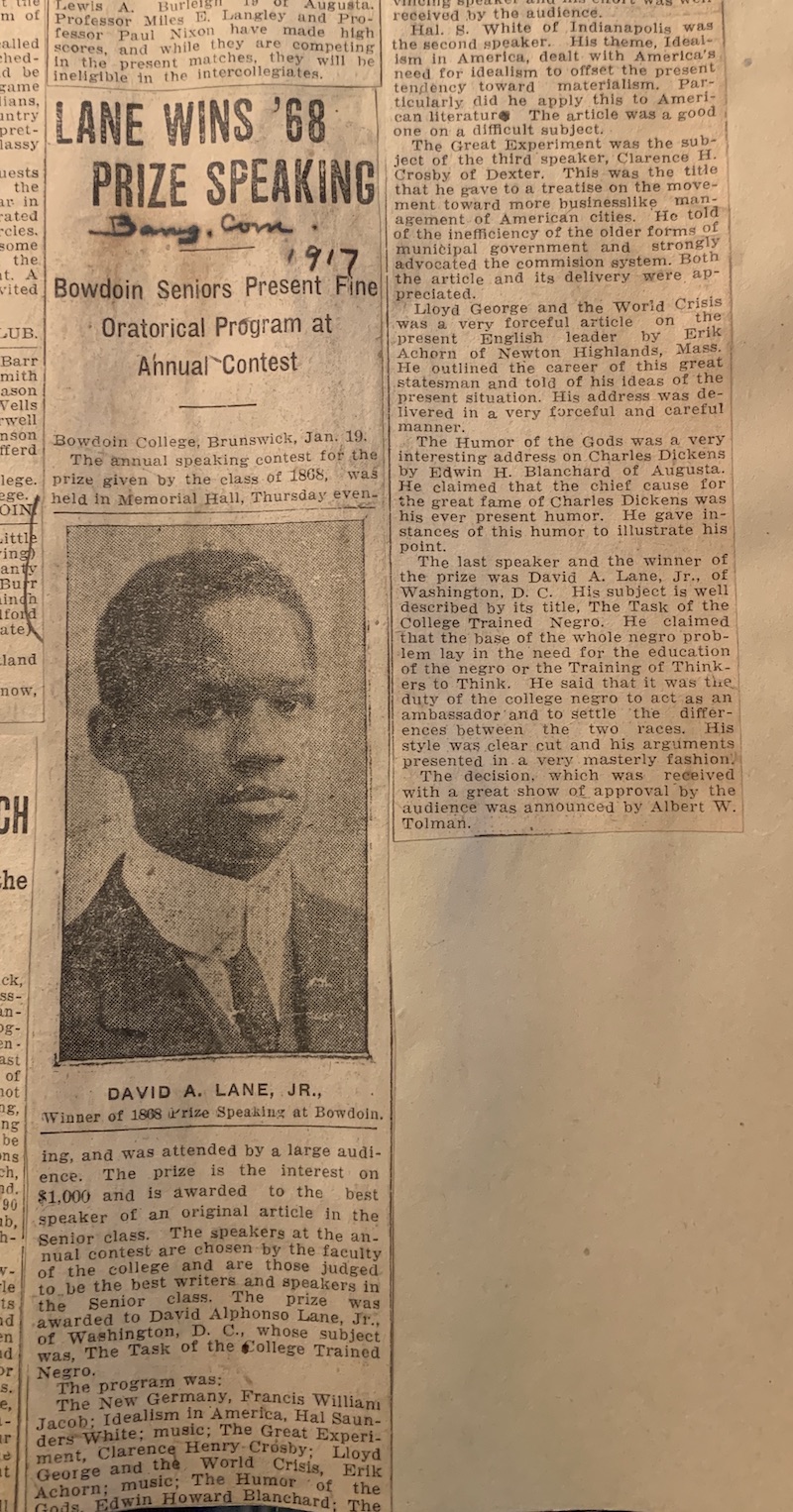

A 1917 speech Lane made in Memorial Hall at Bowdoin, on the task of the college-educated African American, won him the Class of 1868 Prize. In this address, Lane called for greater education for African Americans who could contribute to "settling the differences between the two races," reported a Bangor newspaper. He remained committed to the education of African Americans throughout his career.

Lane's oratory talents caught the attention of the Boston Globe, which ran a dispatch about a varsity debate competition in which Bowdoin defeated Wesleyan University. It reported that Lane—"who was popular at Bowdoin, ranking high in scholarship as well as in the opinion of his fellow students"—was the first black student to "ever represent Bowdoin in any intercollegiate event."

The 1917 Bowdoin Bugle, the College's former yearbook, described Lane as blossoming during his junior year to become "a debater par excellence" who always had a "cheerful word" for other students. "Somehow," the writers continued, "we feel that Dave is the sort of lad who will be successful in later life, and bring credit to Bowdoin and 1917."

They were right.

World War I

At twenty-two years old, Lane was commissioned as second lieutenant under the Reserve Officers Training Corps program. Almost two years later, he was promoted to first lieutenant.

To his disappointment, Lane did not see action during his first military service. "While I cannot help regretting that I did not get 'across,' I feel that I have done the 'bit' assigned to me and in some measure helped to win the war," he wrote to a Bowdoin librarian in January 1919.

But this was not to be the last time he would have a chance to help "win the war."

Academic Career

After leaving the army, Lane earned a master of arts degree in English from Harvard University in 1920. This launched him into a twenty-two-year career as a college professor and administrator.

Following Harvard, he got a job teaching English at West Virginia State College, a historically black university, where just two years later he was appointed dean. He held this position until 1937, when he left for a job as dean for Louisville Municipal College (which later merged with the University of Louisville).

Lane was invested in ensuring African Americans had access to a college education. On an academic leave, he pursued graduate studies in higher education administration at the University of Chicago from 1930 to 1932. From 1930 to 1935, he served as advisor and contributing editor to the Journal of Negro Education. In 1940, he was appointed by the US Commissioner of Education (a position authorized by Congress) to an advisory committee on higher education for African Americans.

In 1975, Bowdoin heard from an old high school mate of Lane's—an Amherst grad named Frederick Parker. Parker alerted Bowdoin to Lane's accomplishments in education, writing that, with help from the faculty at Louisville Municipal College, Lane "undertook to create a college which would rival any college of its size south of the Ohio."

Parker also wrote that Lane waged a quiet campaign to desegregate higher education, specifically in public colleges in Kentucky. Around 1939, he requested an audience with the state's governor to convince him to pursue desegregation. The governor's response was instantaneous. "Preposterous!" he said. "That would call for a change in the laws of Kentucky!" To which Lane replied, "What's the matter with that?" So it was unsurprising—albeit disheartening—that Lane's university contract was not renewed after 1940.

Back to the Military, and Afterwards

The military called to Lane again at the outbreak of WWII, and in 1942 he reentered the army as an information-education specialist. During the next twelve years he served in a variety of roles, including three years in the Pacific, three years at the Pentagon, and two years in Germany as a US Army historian.

During his time in the Pacific, he received an Army Commendation Ribbon for meritorious service. An official US Army statement from this time commends Lane with high praise: "By his outstanding insight into the causes of dissatisfaction, his wide previous experience, tact, and perseverance, Major Lane has helped to increase the general level of morale among Negro troops in this area, thereby effecting more harmonious relations within this command, and reflecting great credit upon himself and upon the military service."

In 1955, Lane transferred to the Retired Reserve, but continued to work in Heidelberg, Germany, as a civilian historian for the US Army. While Lane seemed tickled by his job (he wrote in a letter to Bowdoin that his former professor Herby Bell "would never have thought I'd end up as a historian of any kind"), his old friend Parker was miffed on his account. "Lane was released from the army as lieutenant colonel and reassigned to his same duties in civilian capacity," he said. "This was to prevent his being promoted to a full colnel [sic]; for too many [colonels], looking like him, were not desirable."

Lane retired from this position ten years later after collecting another military decoration for his service.

"Good to Me"

On December 31, 1959, Lane wrote a letter to his former classmate Paul Niven, Class of 1916, expressing his contentment. "Here at the beginning of the 1960s, I can say that the years have been good to me."

But his life was not without sorrow. His first wife, Mary F. Webb, died in 1933. He remarried a woman named Juanita Bobson, a public school teacher. His first son, David Alphonso Lane III, died at the age of eleven in 1935. He had two surviving children: Mary Ethel Lane Cobb, who worked as a physician in New Jersey, and Hugh Webb Lane, who was a clinical psychologist at the University of Chicago and directed the National Achievement Scholarship Program in Illinois, according to Bowdoin records.

David Alphonso Lane Jr., Class of 1917, died on August 20, 1985, in the town of Ossining, New York, at the age of eighty-nine.