Bowdoin Graduates, Professor Help Maine Cities Prepare for Climate Change

By Rebecca Goldfine

Last year, the cities of South Portland and Portland joined forces on an 18-month project to develop a far-reaching climate action and adaptation plan. Besides pledging to reduce greenhouse gas emissions eighty percent by 2050, they are also preparing for rising sea levels and extreme weather events.

Helping to lead the endeavor is Holly Jacobson, who graduated from Bowdoin in 2011 with a major in environmental studies and biology and a minor in the visual arts. She is now a resilience and sustainability consultant for Linnean Solutions, with offices in Portland, Maine, and Cambridge, Massachusetts.

And the project has other Bowdoin connections—another consultant Linnean Solutions enlisted for help is Mary House ’93, a senior principal and board member at Woodard & Curran, an engineering and environmental consulting firm based in Portland. Jacobson also connected with Eileen Johnson, a lecturer and program manager for environmental studies at the College.

Both House and Johnson contributed to an important component in the planning process: a vulnerability assessment. This assessment identifies both the things in the cities that will be impacted—roads, buildings, infrastructure, and the economy—and the people who will be most susceptible to hazards such as rising seas, extreme heat, and wild weather.

Bowdoin's Eileen Johnson discusses this project and how it impacts local communities on a September broadcast of Maine Calling.

Listen at mainepublic.org »

Social Vulnerability

To understand how people will be affected by climate change, we have to first appreciate how the world around us will be impacted.

House and her team identified potential vulnerabilities in the cities' infrastructure, including wastewater and stormwater systems. "If those get flooded and aren’t completely intact, the results could impact water quality, roads, and telecommunications systems," she said.

The vulnerabilities identified in the assessment will serve as a roadmap for the next phase of the planning process—when the project team will be working with city staff, residents, and businesses to identify strategies for increasing the cities’ resilience.

For almost a decade now, Johnson and her classes have been working with Maine towns to help draft strategies for coping with sea surge and other climate change effects. As an expert in spatial analysis, GIS and remote sensing, she regularly helps to develop maps showing how coastal areas will be affected.

Over the years, she noticed a gap in the way communities were preparing for a different world. While data and models were becoming more sophisticated, attention to the human dimensions of the predicted changes would sometimes lag behind.

Tackling climate change will require many people, with many specialities, working together. "Climate change is a multidisciplinary issue, and we are a multidisciplinary team," Mary House ’93 said. This is reflected even in the backgrounds of the Bowdoin participants.

House majored in chemistry and environmental studies at Bowdoin before getting her master's degree in environmental science and engineering from Colorado School of Mines. Holly Jacobson ’11 studied biology, environmental studies, and art at Bowdoin, and earned a master's from Massachusetts Institute of Technology in city planning. Eileen Johnson earned a PhD in ecology and environmental science from the University of Maine in Orono.

"I think a lot about social vulnerability as it relates to climate change—how important it is not to forget the social fabric of a community when we look at the consequences," she said. "We often focus on infrastructure, roads, and buildings that will be impacted, which is important, the communities' dynamics and demographics are also a very important piece."

By social vulnerability, Johnson is referring to people who are most likely to be isolated or incapacitated by storm surges, flooding, or destructive weather. Elderly people living alone—which is not uncommon in Maine—might be at greater risk than a younger person with more resources, or even just more roommates.

One way to determine who is going to be most vulnerable is to know who will be cut off when the roads connecting them to hospitals and grocery stores are inundated or impassable during storms, particularly as sea level rises.

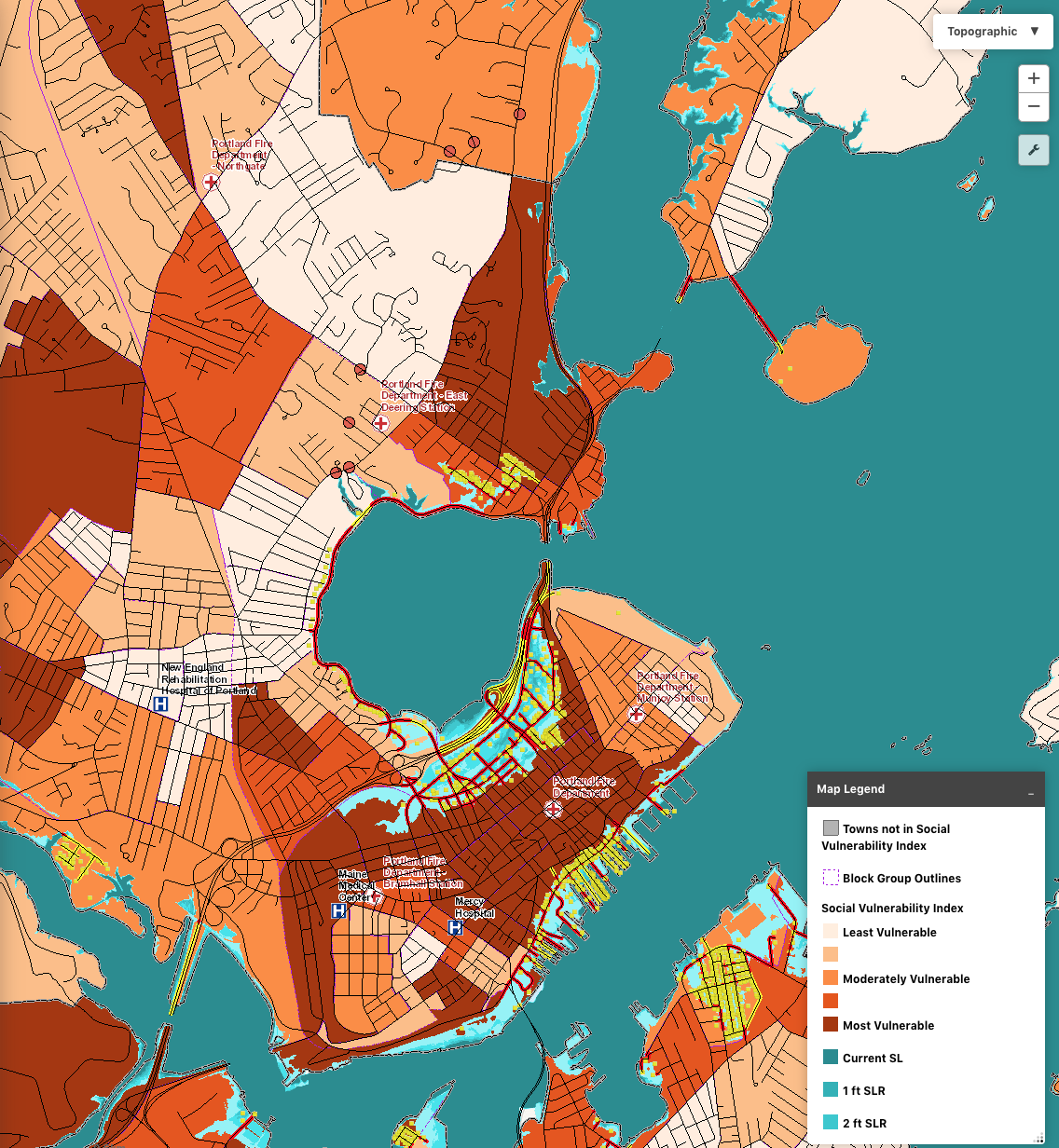

Johnson collaborated with The Nature Conservancy to develop the Maine Coastal Risk Explorer, an interactive tool that allows town officials to see which streets will be impacted by flooding—from a one-foot sea level rise to a six-foot rise. (Current estimates suggest sea levels could rise to eleven feet by the end of the century.) Other collaborators included Blue Sky Planning Solutions. Sea level rise data was provided by the Maine Geological Survey.

In addition to displaying impacted roads at varying sea levels, the digital tool asseses the social vulnerability of regions within towns and cities—ranking them from least to most vulnerable. This assessment is derived from seventeen socioeconomic and demographic characteristics of residents, including socioeconomic status, ages and disabilities, housing and transportation access.

"Our hope is that it allows communities to recognize the areas they should focus on when they're thinking about whether to invest here or there," she said. "It'll help them identify infrastructure investments and timelines to prioritize funding."

Jacobson said that this tool—and the underlying data used to make it—was a helpful way to visualize areas most at risk.

Besides analyzing the economic, environmental, and infrastructure vulnerabilities of South Portland and Portland, she and her team identified neighborhoods prone to flooding, and acknowledged the ways this creates compounding vulnerability for residents, particularly those who live with a disability, who have lower incomes, or who are elderly and living alone.

Besides age, ability, and income, other social differences also may influence how people weather climate change. Those who are self-employed or employed in natural resource-based industries have less of a buffer if their work is interrupted by flooding. And new arrivals to Maine who don't speak English could be in more danger during an emergency if they miss official orders.

"Those factors act as a multiplier in how climate change, from sea level rise to extreme heat, would be experienced," Jacobson said.