Research Team Studies Road Salt Pollution in Maine Lakes

By Rebecca Goldfine

For the past seventy years, states in the US that suffer through fierce winters have treated their roads with rock salt to melt dangerous ice. But all of this salt has to go somewhere—and a portion of it ends up getting diluted and running into freshwater lakes.

In the past few decades, some of Maine's freshwater ecosystems, particularly the ones close to roads, have been testing higher for sodium chloride, the chemical basis of most road salt.

To better understand how all this salt is affecting the ecology of Maine's lake waters, a Bowdoin professor and two student assistants—Utku Ferah ’21 and Elizabeth Baker ’22—are spending the summer collecting data on a freshwater zooplankton called Daphnia. Scientists study the tiny Daphnia crustacean because it, like a canary in a coal mine, can indicate at what level a contaminant is safe for an ecosystem.

"What is also important about Daphnia is it is a keystone species," Assistant Professor of Biology and Environmental Studies Mary Rogalski said. "It grazes on algae and keeps the algae levels lower in lakes, and it is also a food source for higher predation levels in the food chain, like fish. So if it begins to die off, there could be big consequences for the rest of the lake foodweb."

Maine lakes show a lot of natural variation in their salt concentrations, in addition to possible inputs from road salt. To test the hardiness of Daphnia in a range of conditions, Rogalski's team has identified three study lakes that differ in their salt concentrations.

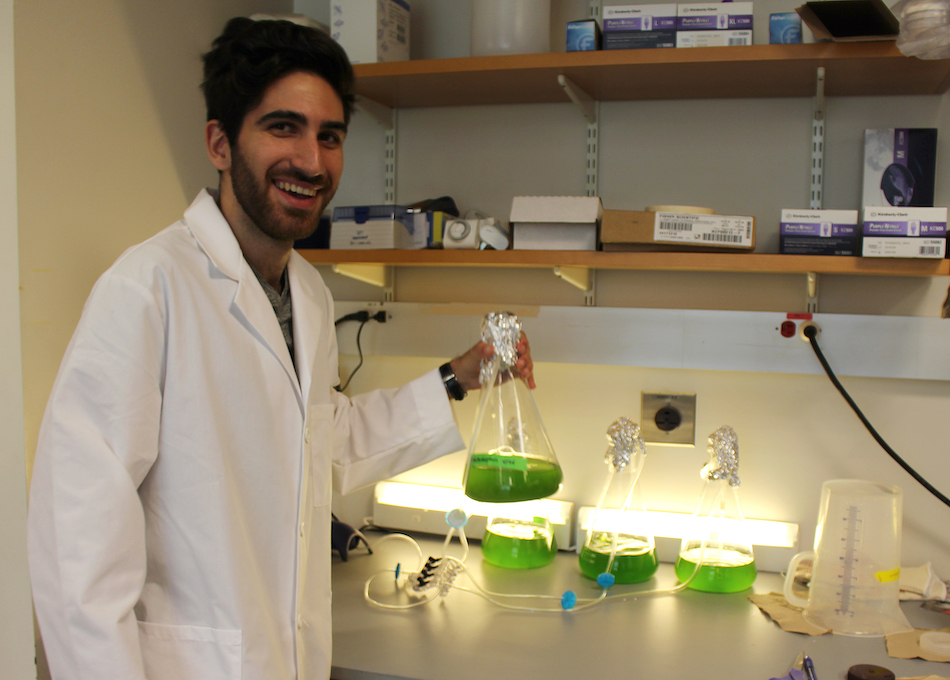

In the lab, Ferah has been asexually breeding Daphnia from each of these lakes in tiny beakers, and feeding them homegrown algae.

"The great-great-grandchild of the Daphnia we collected from the lakes are the ones we will use in our experiments," Rogalski said.

These descendants are clones with the same genetic makeup as the original Daphnia, but they won't have any plastic traits or diseases their relatives might have had. The researchers will then conduct an experiment to determine how well suited the Daphnia are to the different types of water they inhabit.

Wintery Driving Conditions and Lakes

While sodium chloride road salt is the most widely used type of salt on snowy, icy roads, Ferah said there is an alternative that might be better for Daphnia—road salt made up of calcium chloride. (Of course, this combination might have unintended effects on other species.)

To avoiding spreading salt on their roads all together, different states have also experimented with pickle brine, sugar beet juice, ash, coffee grinds, cheese brine, and potato juice. Engineers have suggested using solar panels instead of asphalt to melt the snow.

"Or we could be more aware of what salt we're putting near what watersheds," Baker said.

While Ferah is working in the lab, Elizabeth Baker ’22 and Rogalski have traveled to twenty-one lakes, from York Pond in southern Maine to Heart Pond near Acadia, to collect Daphnia and see how they're faring under different salt conditions.

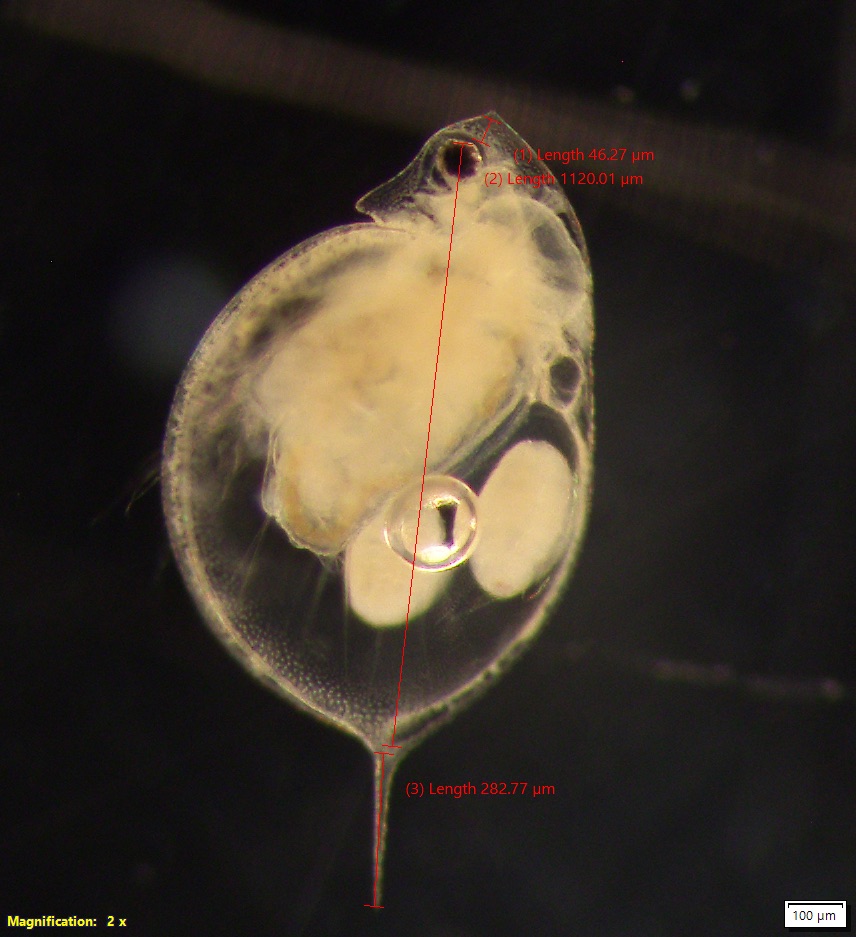

After returning to the lab with their specimens, they study them under a microscope, looking for minute variations in their bodies. "They create predator defenses," Baker explained, such as spikier spines or larger helmets around their heads. "If they're bigger and spinier, they're better defended against predators."

Rogalski said Daphnia with weaker armor might be a reaction to variation in lake water quality, but they could also be responding to other factors, such as lake temperature or predators. "In a field project like this it can be hard to tease apart the source of that variation, but the patterns we see could be a great jumping off point for future research," she said.