Telling the Untold Stories of Peary's Arctic Voyages

By Symone Marie Holloway '22A new book by two Bowdoin scholars, Peary’s Arctic Quest: Untold Stories from Robert E. Peary’s North Pole Expeditions, goes beyond one-dimensional retellings of Peary's Arctic treks and instead delves into the lesser-known stories of those who supported him.

In the field of Arctic studies, many scholars and history enthusiasts focus on the question of who reached the North Pole first. Did Peary actually reach the North Pole? Did Frederick Cook reach the North Pole before him?

But Genevieve LeMoine, curator of the Peary-MacMillan Arctic Museum and Arctic Studies Center at Bowdoin College, and Susan Kaplan, Bowdoin professor of anthropology and director of the Peary-MacMillan Arctic Museum and Arctic Studies Center, believe there are more interesting aspects of the expeditions to explore.

Their book, Peary's Arctic Quest: Untold Stories from Robert E. Peary’s North Pole Expeditions, has just been released by Down East Press. Based on over two decades of research, it fills in the gaps in our knowledge of Peary and his voyages.

Unearthing Narratives

The incentive for the book dates back even further. Reflecting on events in 1984 that marked the seventy-fifth anniversary of the North Pole expedition, Kaplan was left unsatisfied with all the focus on the infamous question. So in 2008, when the Peary-MacMillian Artic Museum opened an exhibition marking the 100-year anniversary of Peary's Arctic journey, "Northward Over the Great Ice: Robert E. Peary and the Quest for the North Pole," it focused instead on the narratives of those who assisted Peary. In the end, there were only two photographs of the famous explorer featured in the show.

"Peary is the name that everybody recognizes," LeMoine said, "but there were a lot of people working with and for him so he could travel to the North Pole. We really wanted to focus on those people—his family, the Inuit, scientific assistants, financial backers—and on the technological innovations that went along with the expedition."

Expedition literature and archived works in the show revealed gripping story lines of cultural contact. Photographs showed women and children who were often ignored in previous retellings of the quest. Matthew Henson, Peary's African-American co-explorer, was also featured prominently.

But Kaplan and LeMoine were sure there were more stories to unearth and continued their research.

Digging Even Deeper

Turning to Bowdoin's archive and others, LeMoine and Kaplan looked beyond the journals detailing the months Peary's expedition spent on sea ice and instead sought resources describing the time before and after. They also reached out to relatives of expedition members—a decision which proved to be fortuitous.

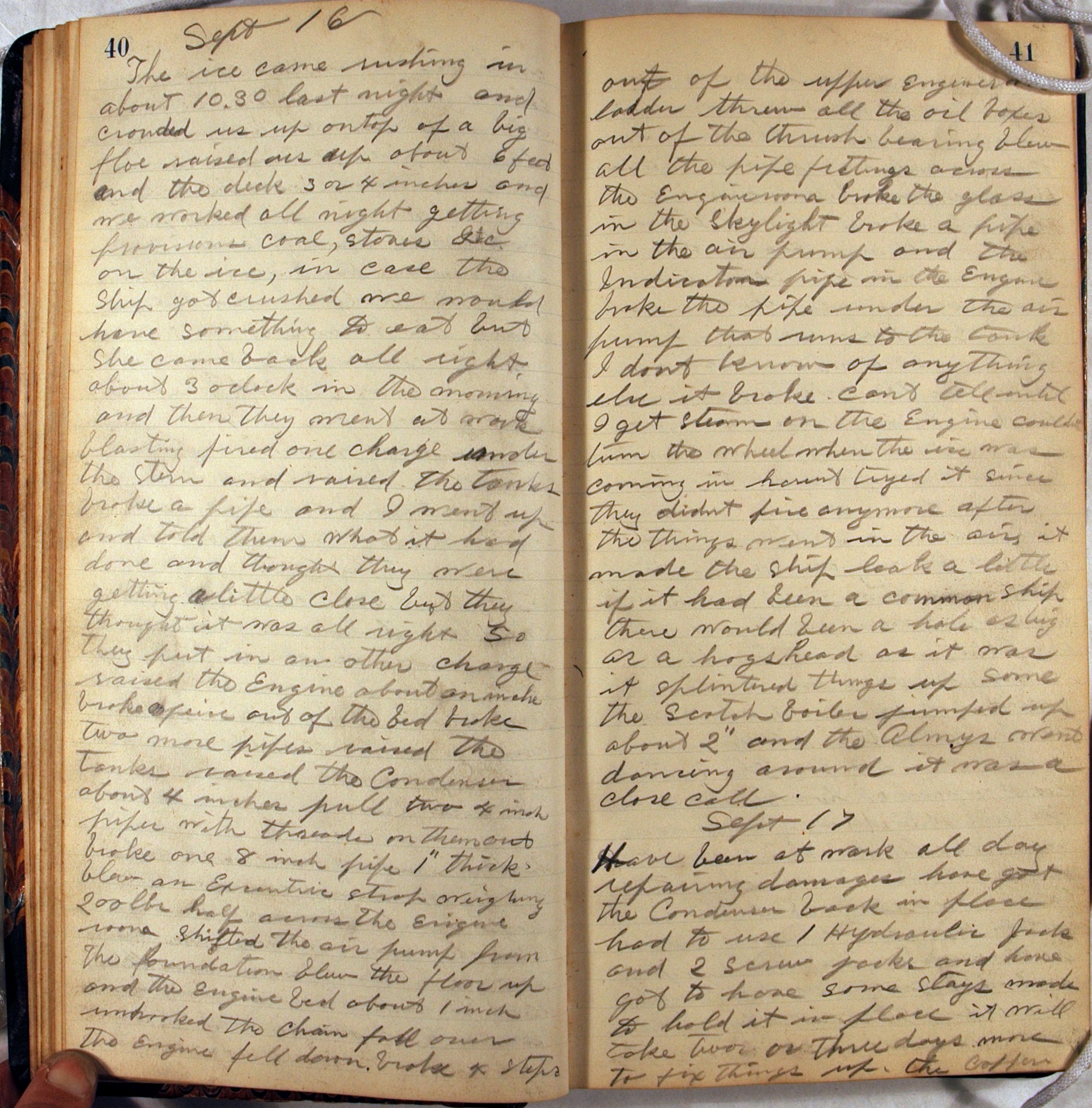

"There was a man named George Wardwell who was the chief engineer of the vessel SS Roosevelt, and his family saved his journals," Kaplan said. "No one knew that he even kept journals!"

Wardwell was charged with keeping the ship running, and his chronicles offer insight and explanations for technical and mechanical details—such as how sea ice threatened the vessel—that were not mentioned in other documents.

"It just was by accident that we read that the Wardwell family, who were from Bucksport, Maine, possessed the journals," said Kaplan. In sharing them, the family members also mentioned that they once had photo negatives from the expedition—but had lent them to someone who never returned them.

Kaplan wrote an article for the Bucksport local newspaper asking for information about the photographs. Three weeks later a town barber called, saying that he remembered that the negatives had changed hands in his shop.

Kristi Clifford, Kaplan's previous administrative assistant, used her sleuthing skills to discover the name of the man who had received the pictures, only to learn that he had passed away a year earlier. She then tracked down his stepdaughters, who relayed the disappointing news that after they sold their stepfather's house, they had donated some of his interesting possessions to historical societies in Maine. Undaunted, Kaplan and LeMoine contacted historical societies. But none of them said they had any helpful information.

Acting on a hunch, Kaplan decided to visit the historical societies in person to look for the objects that were not listed in their catalogs.

"The very first place I went was the Castine Historical Society, and they thought I was crazy, they thought I was mad, because I asked, 'Would you let me see all of your uncatalogued and unidentified collections?' And they were like, 'Whatever lady.' But within an hour we had found them: a scrappy envelope with the handwriting of some of the people involved. You would pick up a negative and there was an Inuit in polar bear skin pants with an individual's name inscribed in it," recalled Kaplan.

"That was really a triumph," laughed LeMoine.

Travel to Cape Sheridan

Based on their findings up to that point, in 2011 the National Science Foundation awarded LeMoine and Kaplan a grant to fund a research trip to Cape Sheridan, on the northeast corner of Ellesmere Island, across Nares Straight from Greenland. Peary had frozen his ship into the ice here, and the Inuit, who he had brought from Greenland, set up camps on shore.

"The fieldwork was the most fun part of the research," recalled LeMoine. "It was the best way for us to more fully grasp what the experience of the Inuit had been like on the expedition. I work in the area of Greenland where they had come from, and to see the contrast of landscapes . . . it gave a real sense of how alienating it must have been." Cape Sheridan is more forbidding and bleak than northwestern Greenland, with much more ice cover.

While on the island, the two researchers all more fully understood the ominous refrain in Wardwell's journal: "The ice is running. I can hear the ice running." Or, on better days: "The ice is quiet."

Kaplan said that when they landed at Cape Sheridan, the sea was choked with ice that wasn't moving. "But then, near the end of our stay, we could hear the ice running," she added. "We could really understand the stress. Every single day Wardwell was listening for danger. That's fifteen months of unrelenting stress."

Peary's Arctic Quest: Untold Stories from Robert E. Peary’s North Pole Expeditions is available at the Peary-MacMillan Arctic Museum and at bookstores.

"There's still more work to be done," Kaplan said. "Our book is not the final word. We started to tap into the gender and race issues, but there are still more archives to be explored. We hope that people will see the history more broadly and want to historically contextualize it better than it has been done in the past."

A Conversation with the Authors, July 31

In the footsteps of Peary's Arctic Quest, from Brunswick to the edge of the Polar Sea, is a book launch and conversation with Susan A. Kaplan and Genevieve M. LeMoine about their newly published book, Peary’s Arctic Quest: Untold Stories from Robert E. Peary’s North Pole Expeditions (Downeast Books, 2019). Copies of the book will be available for purchase at the event.

The event will take place from 3:30 p.m. to 4:30 p.m. in the Beam Classroom in the Visual Arts Center on July 31.