Mapping Africa: Traditional Structures and Contemporary Outcomes

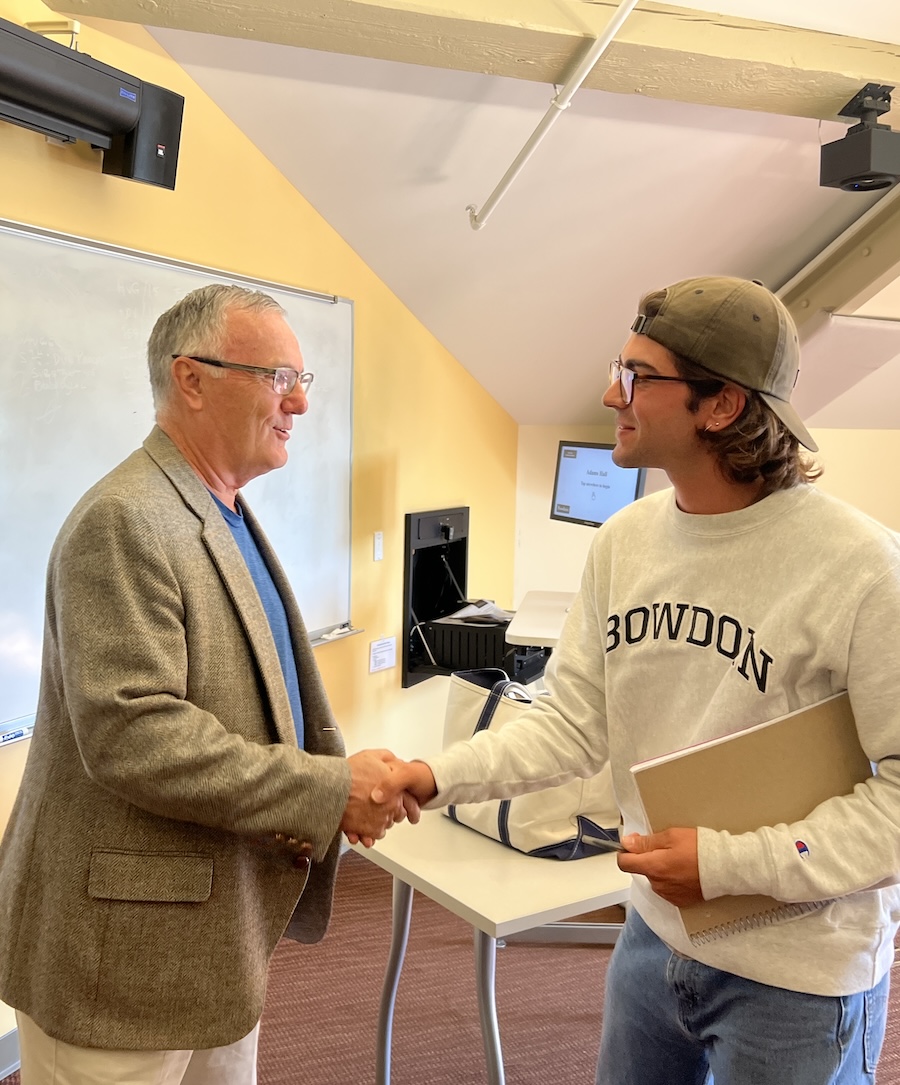

By Symone Marie Holloway '22Abby Gonneville ’21 is working with Associate Professor of Government Ericka Albaugh to provide mapping data to help answer a question about the lingering effects of precolonial governance systems in contemporary Africa.

Gonneville has a summer grant from Bowdoin's Gibbons Summer Research Program, which was established by John A. Gibbons Jr. ’64 to support students assisting faculty members with technological research in interdisciplinary fields.

The work she is doing for Albaugh will provide data and maps for a published article and lay the groundwork for classes Albaugh teaches on African politics, ethnic politics, and language politics.

Gonneville explained the background for her project. "About twelve years ago, two economic scholars argued that the more precolonial political centralization there was in Africa, the better the quality of governance in contemporary Africa. So, a lot of this project is tracing precolonial structures and postcolonial outcomes," she said.

Interestingly—and problematically—more recent economic analysis has proposed that the 2007 argument by those economists, Nicola Gennaioli and Ilia Rainier, might not apply to all countries and contexts. Rather, what might be more influential in shaping contemporary governments is the national process of selecting leaders or the region's democratic history.

"Their work set the groundwork for a lot of subsequent research, and we want to both acknowledge its importance and improve on it," Albaugh said. "Quantitative analysis is good for seeing broad patterns, but you need to get down in the weeds to see whether it makes sense on the ground within particular countries," she added.

To apply pressure to the 2007 theory, Gonneville and Albaught are reconstructing the process Gennaioli and Rainier used in their study. But they are using a different historical map for the basis of their analysis. Gennaioli and Rainier based their findings on the Atlas Narodov Mira, a 1964 Soviet document that attempted to distinguish ethnic groups across Africa.

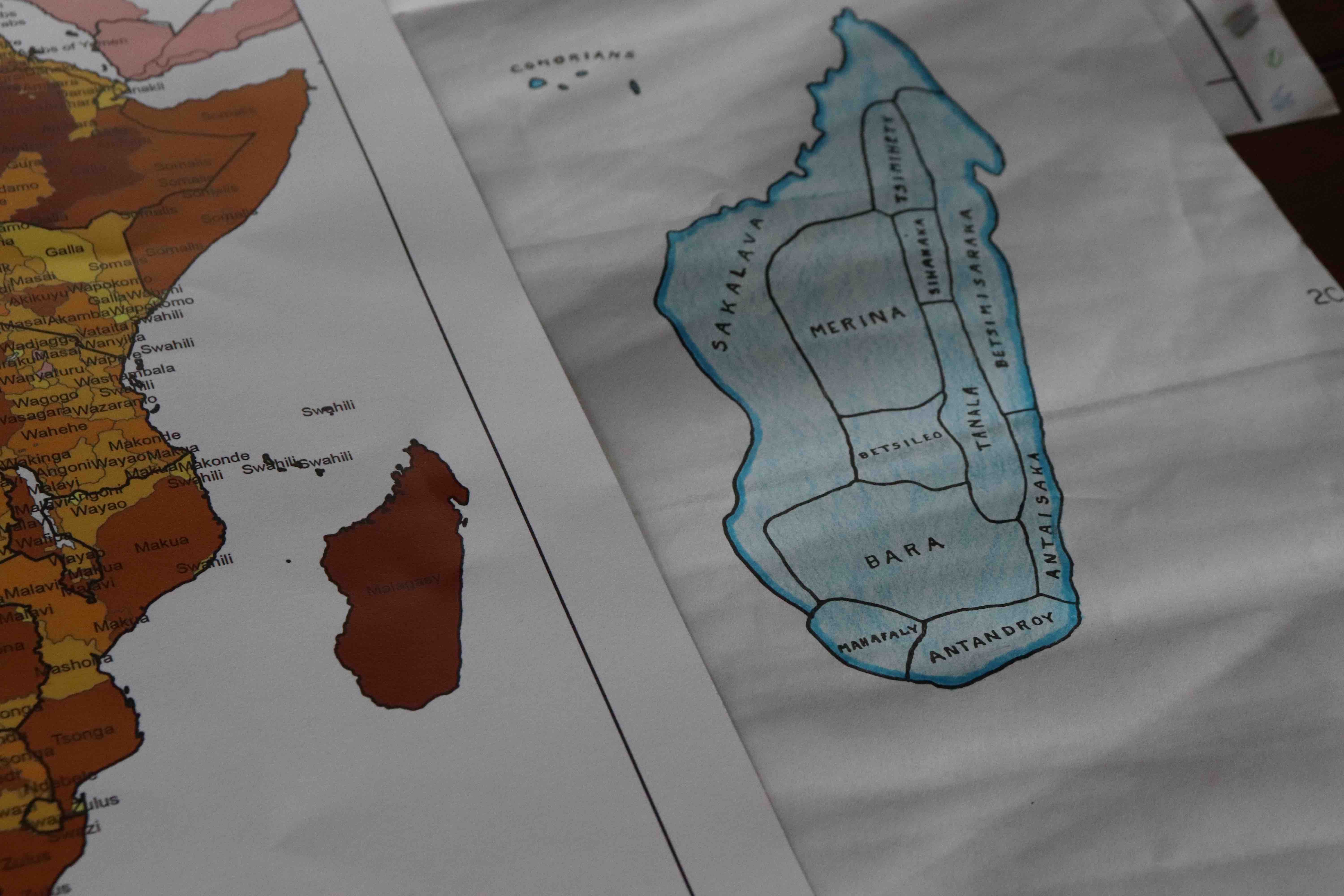

Gonneville's biggest task has been matching cultural groups documented on the Atlas Narodov Mira of Africa to the Murdock Map of Africa, which was created by an anthropologist in 1959 to trace ethnolinguistic groups across the continent.

Compared to the blunter Narodov-Mira map, the Murdock map and corresponding database provides more details about subgroups of dialects and cultural groups. It also "assigned comparable attributes to groups, such as their methods of selecting leaders or their structural hierarchy (e.g., centralized versus loosely organized)," according to Albaugh.

On the Narodov Mira map, "cultural groups aren't done justice," Gonneville said.

An example of the discrepancies Gonneville is trying to reconcile can best be exemplified by how Madagascar is represented on both maps. The Murdock map features more than ten subgroups that speak Malagasy, the main language spoken in Madagascar. The Narodov-Mira Atlas map only lists one group that speaks Malagasy.

She and Albaugh will use the mapping data to discern precolonial centralization in cultural groups, or how hierarchically organized they were. They then can trace regional histories from independence to today, looking at current government functionality and democracy.

Albaugh expressed appreciation for the work Gonneville has done this summer. "It takes extraordinary patience and methodical care to sift through such a large quantity of data and make it ready to project onto beautiful maps that people can understand intuitively," she said. "That scholarly diligence is a special quality that Abby possesses, and I am so proud of her work."

Last summer, Gonneville worked as a research assistant for the government and legal studies department, and she and Albaugh used ArcGIS to collect survey data in a digital form. This is where the technology comes in. ArcGIS is a geographic information system that can create maps and analyze data geographically. The data in the program last summer was used by students in Albaugh's language politics class to visualize languages spoken in various countries around the world. The program is also helping the duo with their research this summer.

Gonneville, a government and sociology double major with a minor in gender, sexuality, and women's studies, would like to continue working with maps in the future. "I can say that I have a newfound appreciation for them," she said and laughed.