Communism in Asia: the European Factor

By Tom PorterAssociate Professor of Government and Asian Studies Christopher Heurlin is to spend the upcoming academic year in Germany. At first glance, this may seem a curious destination, given that Heurlin’s area of expertise is Chinese politics. However, as he explained, Germany is rich in archival resources that will shed important light on the durability of some communist regimes in Asia.

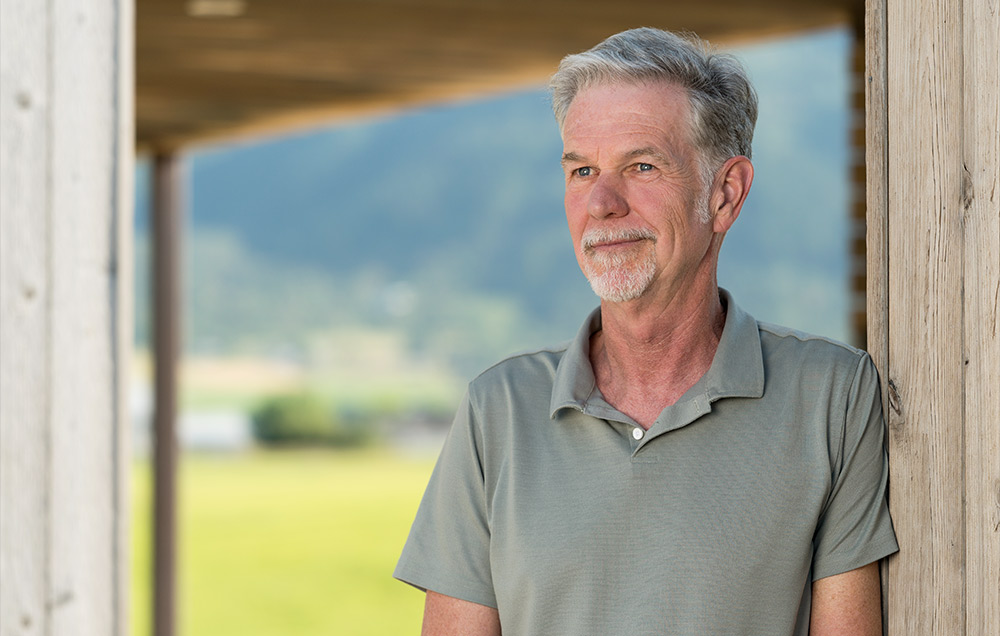

Christopher Heurlin

Heurlin has been invited by the Institute of Sinology at the Freie Universität Berlin to serve as a visiting researcher for the 2019-2020 academic year. His research is being funded by a Fulbright award and a grant from the German Academic Exchange Service (or DAAD, to use its German language acronym.) The project he’s working on is called “The Enduring Power of Communism in Asia,” and he plans to make it the basis for his next book.

“Essentially, I am looking at the role that Soviet and Eastern European aid projects had in helping to consolidate and strengthen communist regimes that emerged in Asia,” said Heurlin. Specifically, he’s looking at China, North Korea, Vietnam, and Laos, where communist regimes endure to this day. Also included in the study are Mongolia and Cambodia, which abandoned communism in the early 1990s. “Why did some regimes fail while others have endured?” is the question Heurlin wants to address.

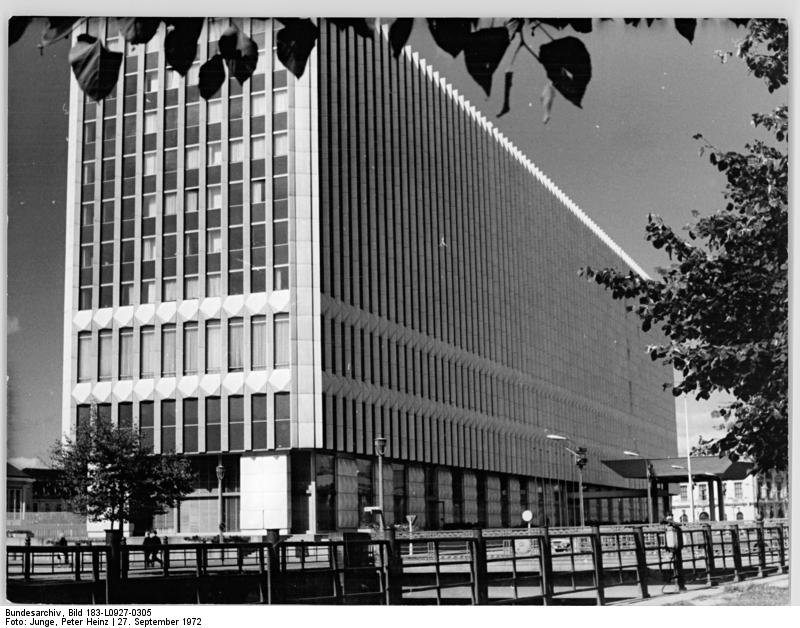

He’s planning to spend several months studying the archives of the East German Foreign Ministry, paying special attention to reports from communist Asia. “I’m largely drawing upon diplomatic traffic between the Foreign Ministry and the East German embassies in Ulan Bator, Vientiane, Beijing, Hanoi, Pyongyang, and Phnom Penh,” explained Heurlin. His thesis is that, in the successful cases where communism has persisted, robust aid projects plowed Eastern European money into factories and state-run collective farms, providing employment for the population and helping these often newly emerged communist regimes build up their tax base. “Importantly,” he added, “military aid helped them also build up oversized security forces to coerce the population.”

Heurlin said that, while this aspect of diplomatic history has been studied by other historians, his comparative approach, asking why some regimes survived the end of the Cold War and others didn’t, is an understudied angle. During his time in Berlin, Heurlin, who is fluent in both Chinese and German, will be fully utilizing his language skills.