The Problem with Oscar-Winning Movie Green Book

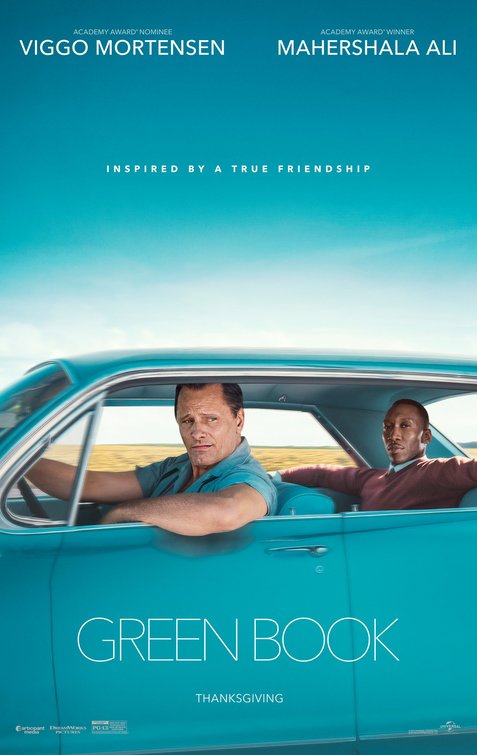

By Tom PorterGeoffrey Canada Associate Professor of Africana Studies and History Brian Purnell shares his thoughts on the Oscar Winning movie Green Book. Inspired by true events, it tells the story of African American concert pianist Don Shirley and his tour of the racially divided Deep South in 1962.

Shirley travels in the company of driver and bodyguard Frank “Tony Lip” Vallelonga, a tough Italian American who holds racist views himself, at least at the start of the movie. The two characters grow closer as they navigate the challenges of “Jim Crow South” and eventually become friends.

“That’s a good story, and it makes for a good movie,” says Purnell, “but the two characters, who start their journey in New York City, didn’t have to go to the South to experience in-your-face divisive racial discrimination. They could have got it right there in the city where they lived.”

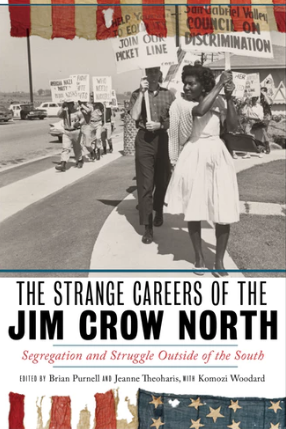

Jim Crow North

Purnell, who is well versed in America’s racial history, says his main criticism of the movie is that it presents the idea that the history of racial discrimination exists only in the South. He is coauthor of the newly published The Strange Careers of the Jim Crow North (NYU Press, 2019), which demonstrates how institutionalized racism in the US was not confined to the southern states, as the movie Green Book suggests.

“The movie’s message has to do with the reconciliation and friendship and camaraderie that comes from two people struggling together against the enemy of racism. And that has to happen in the South in the movie, which means it completely overlooks how there’s discrimination in restaurants, clubs, housing, jobs, and policing in New York and other northern cities.”

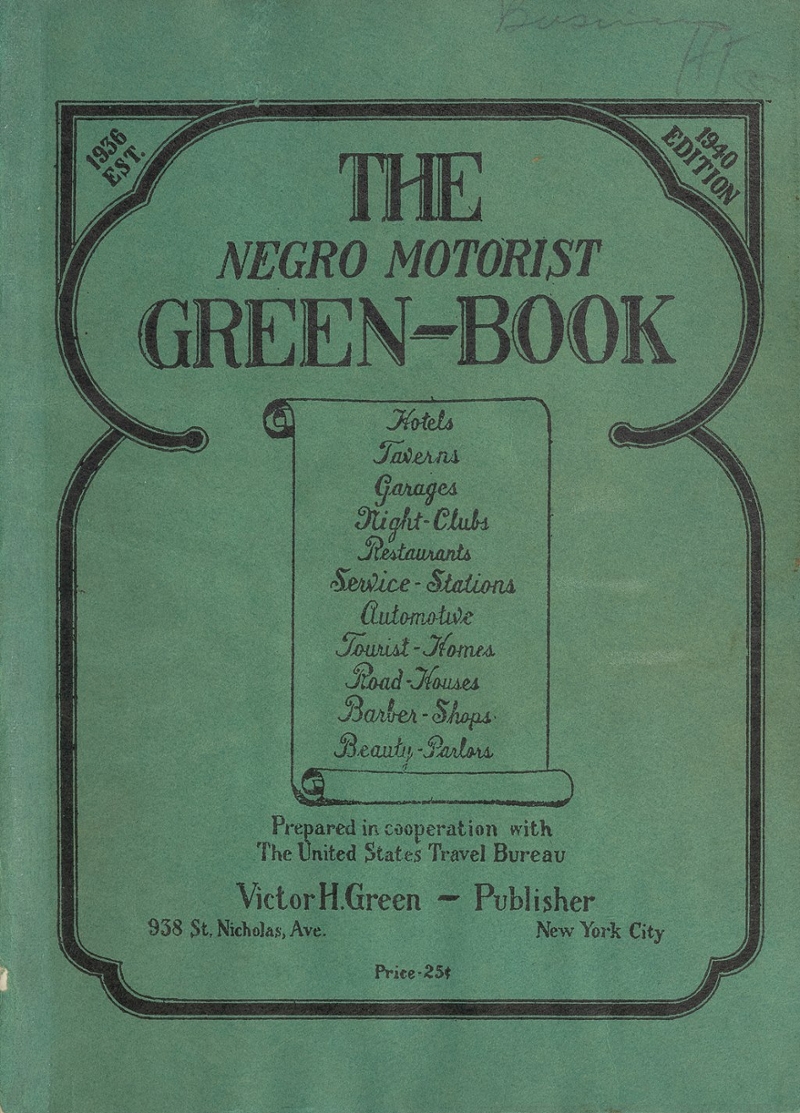

Purnell goes on to point out that the publication from which the movie gets its name—The Negro Motorist Green Book, a guide for African American travelers—began in New York City in 1936 as a way to let black visitors know where they could safely eat and sleep. The movie, he says, suggests it’s just a guide book for the South.

How did racism in the South compare to racism in the North in the early 1960s?

That’s a good question, says Purnell. Racism in the South had a more dangerous edge and definitely posed more of a physical threat, he explains. “Up until the Voting Rights Act of 1965, black people risked their lives, or at least their livelihoods and physical well-being, if they tried to vote. Economic possibilities were also extremely constricted, with most of the black population being agricultural laborers working in debt peonage.”

More jobs were available to black people in the North, but racial discrimination was enshrined in many policies, and African Americans found themselves being treated as second-class citizens. This was especially true in times of economic stress, says Purnell, when good-paying jobs were reserved for the white population.

“Black people were constricted to ever-limiting sectors of poverty in the North. If you add to that the inability to move to different places due to race and the ways that school zoning policies protected coveted school districts for middle class, or just predominantly white citizens, then the North’s style of Jim Crow, while not-threatening if you go to the polls, has equally long-term negative effects on people because of race. The movie tackles the issue of racism in America without acknowledging any of this.”

But is it a good movie?

If you ignore these inaccuracies, says Purnell, Green Book has a lot to offer. “I like movies and I think a story about racial reconciliation is a good thing. The white character is a bigot – but by the end is completely changed. The fact that this buddy-flick, feel-good Hollywood story might encourage Americans to take a less prejudiced view of others made me appreciate the movie.” The bottom line on Green Book for Purnell is this: “It’s a good movie, but bad history.”