Parts of Campus Bring a Light to Wabanaki History

By Rebecca GoldfineMaine's Wabanaki tribes and allies are shifting the way people in Maine, including at Bowdoin, are engaging with the state's colonial history and the injustices inflicted on the indigenous population.

Several recent initiatives at Bowdoin have encouraged students to pursue a deeper understanding of the impact of colonial history on Native Americans, and to learn how Native people today are contributing to the state's politics, culture, and environment.

A New Relationship to the Land: The Outing Club

In late February, student trip leaders gathered at the Schwartz Outdoor Leadership Center for an interactive workshop about the effects of European colonization in Maine and the treatment of Native people by the US government. Many of the Bowdoin students said this was a story they had never learned in full.

The workshop, offered by a joint state-Wabanaki initiative called REACH, is meant to be easily recreated at churches, libraries, businesses, and schools. Designed for non-Natives, its intention is to reflect on Maine's colonial past, as well as the state's current relationships with Native people.

To bring Native issues to the forefront of the Outing Club and the wider campus community, Tess Hamilton, assistant director of the Bowdoin Outing Club (BOC), invited REACH to offer its student workshop at Bowdoin, and she is also organizing a daylong event for faculty and staff at the end of May. So far seventeen people have signed up for this workshop, and she says there is room for more.

Inspired by these events, a group of eight students is learning Native names for flora and fauna, and for Maine's natural features—like its mountains and rivers. They plan to put together information for trip leaders so they can speak about the land's history when they lead groups into the outdoors.

"The Outing Club is a place on campus that offers students a lot of intimate interactions with the Maine landscape," Hamilton said. "I have a lot of gratitude for the privilege of getting to spend time in the Maine outdoors, and I want students to learn about its rich history and the relationship that Natives have with the land here."

She added, "This awareness not only acknowledges existing Native communities but also enhances the depth of our programming."

A History Workshop at the Schwartz Center

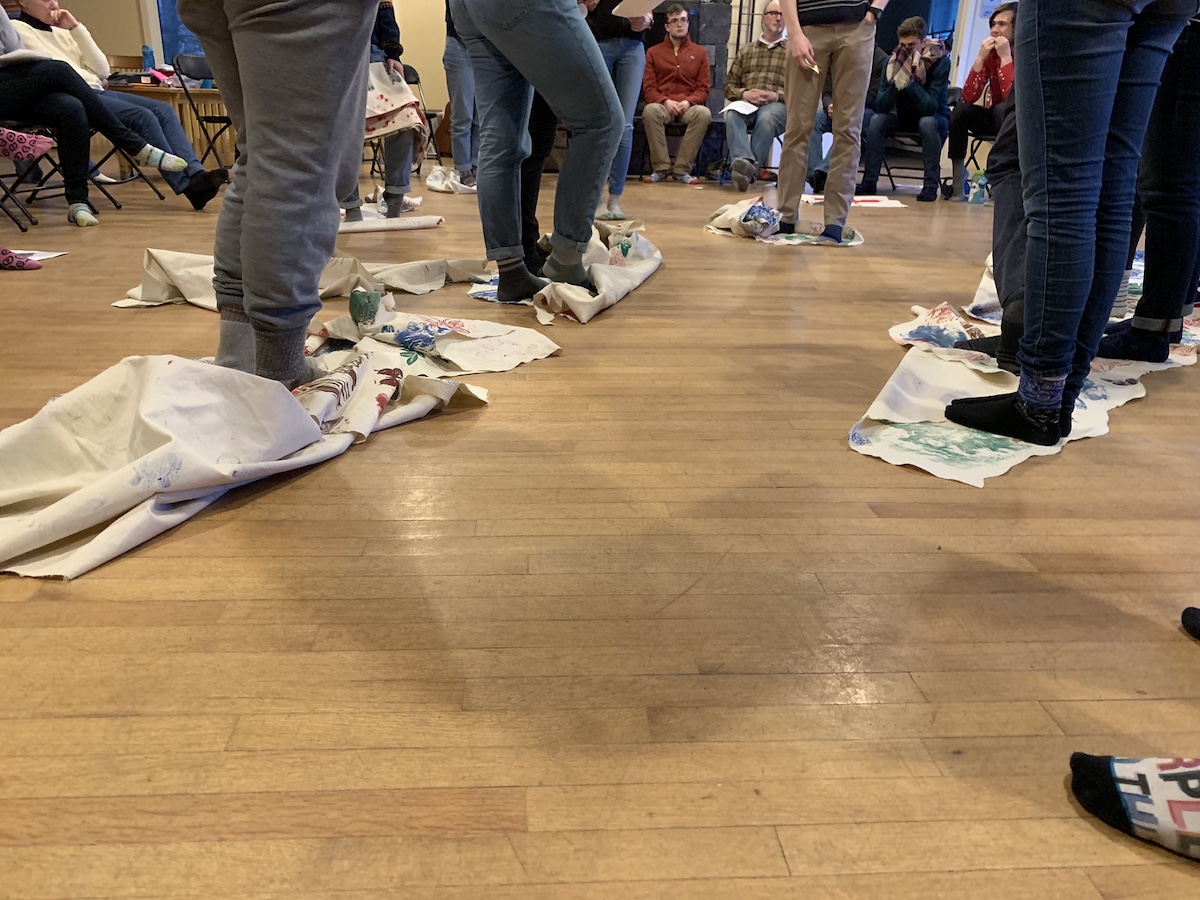

The interactive workshop is an intense and emotional event that is difficult to sum up briefly. As one of the two leaders of the recent Outing Club workshop said, "We cover 450 years of history in two hours."

Before they began, the two workshop leaders—Carla Hunt and Julie Beckford—spread out, in the middle of the room, a large cloth map of Maine printed with indigenous plants and animals. The map—the symbolic focus of the workshop—is designed to be stepped on by participants, taken apart, and put back together as the story of the land and its people unfolds.

Hunt began by noting that before the Europeans arrived, at least twenty indigenous tribes lived across the land "we know as Maine." Today, only four remain: the Maliseets, Micmacs, Passamaquoddy and Penobscots. Collectively they're called the Wabanaki, or people of the dawn.

"Maine was one-hundred percent Wabanaki territory," Hunt said. It is thought that the first people settled in Maine thirteen thousand years ago. The Europeans arrived in the sixteenth century. "Now Wabanaki control less than one percent of the land."

The volunteers then led the students through a demonstration of how the population numbers of Native Americans plummeted after the settlement of Europeans—from disease, war, and loss of territory resulting from what they said were broken treaties and unjust laws.

Hunt told the students, however, that they wouldn't be dwelling only on defeat and despair: "We're talking about oppression, but also we're talking about resilience and resistance of the Wabanaki for over four hundred years."

Bowdoin and the Truth and Reconciliation Commission

Moving into contemporary times, the workshop's narrative focused on how authorities in Maine, throughout much of the 20th century, systematically removed Native children from their homes and placed them in foster care with white families.

"Many children suffered. They had trouble assimilating back into their culture; they didn't speak their language or know their traditions. They didn't have loving care," according to the REACH workshop script.

In response, Maine-Wabanaki REACH convinced Maine's governor and its tribal chiefs to commission an official investigation into the state's discriminatory child welfare practices in 2013.

In 2015, the Maine Wabanaki-State Child Welfare Truth and Reconciliation Commission declared that the welfare practices against Native communities and children amounted to "cultural genocide." It also pointed to the disproportionately high rate at which Native children continue, even into present day, to be separated from their families and communities.

The TRC's archive are held by Bowdoin's Special Collections for safekeeping and public access, making the College a central point in Maine-Wabanaki REACH's efforts to educate people about the history of the Wabanaki. The holdings include more than two hundred personal histories of Native Americans affected by Maine's discriminatory child welfare system.

In the fall, Assistant Professor of Anthropology Willi Lempert taught a course called Contemporary Issues of Native North America. He and his students took advantage of the archive's proximity to investigate this local issue.

The library also hosted a screening of Dawnland in November, a documentary about the TRC. The filmmaker and co-director of the Maine-Wabanaki REACH Program spoke on campus and visited Lempert's class.

"It is really important for us in this course to focus on the tribes and people who are in the area," Lempert said. "You never want to send the message, which is so deeply ingrained in history, that indigenous people are far away, both in terms of space and time. Indigenous people are here and now, not there and then."

One thing that makes the TRC archive unique is that while it reaches back into history, it also shines a light on a current story, one that is still developing, according to Marieke Van Der Steenhoven, the education and outreach librarian for Bowdoin Special Collections. There are eight thousand or so Wabanaki in Maine who continue to advocate for fairer and more humane treatment for their children, families, and communities.

"The TRC archive is contemporary, it is telling a contemporary story," Steenhoven said. "We're in the midst of it."

To get more involved in these efforts, or to attend the May Maine-Wabanaki REACH workshop, contact Tess Hamilton, thamilt2@bowdoin.edu.