Bowdoin Professor Nominated for Top Hispanic Literary Prize

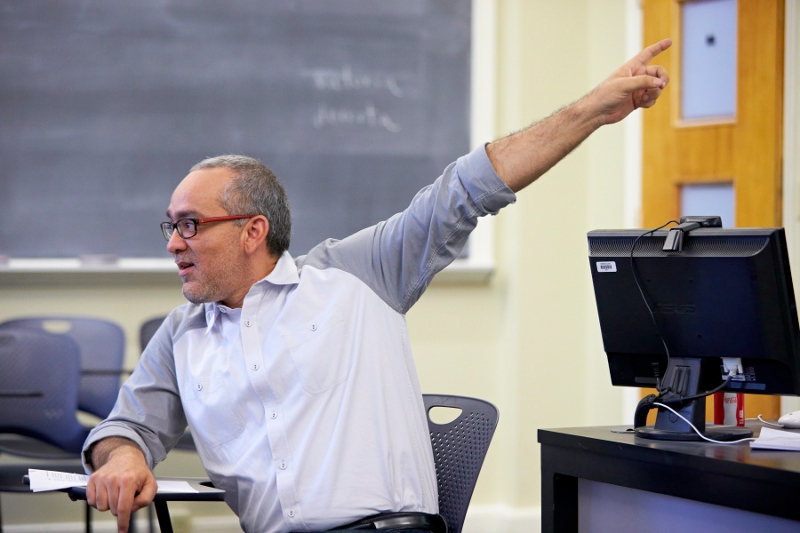

By Tom PorterAssociate Professor of Romance Languages and Literatures Gustavo Faverón Patriau is one of five finalists for arguably the most prestigious literary prize in the Spanish-speaking world.

Faverón Patriau’s latest novel, Vivir Abajo (2018), which translates as To Live Underneath, is short-listed for the biennial Mario Vargas Llosa Prize, an award given by several Spanish and Latin American institutions to the best novel published in Spanish during the last two years. The winner of the prize, which comes with a $100,000 award, will be announced on May 30 at the Guadalajara International Book Fair in Mexico, the second-largest book fair in the world and the largest one in the Americas.

The novel, which Faverón Patriau describes as darkly humorous, is set in the US and Latin America and explores themes of political violence, revenge, and madness. At the center of it all is a very complicated father-son relationship.

Q&A with Gustavo Faverón Patriau

How did the novel come about?

Some three years ago, I saw a movie directed by a Peruvian friend of mine, more or less at the same time that he read my previous novel, The Antiquarian. We ran into each other in Lima once and, over coffee, talked about our impressions of each other´s work. By the end of the conversation, we decided we would try to work together on the script for his next movie.

I told him about a couple of short stories I was working on and promised him I could bring out a whole film plot from them (which was a little bluffing on my side). I returned to Brunswick and started working on that. I remember writing 100 pages the very first day. One of the stories was about a young American man who commits a crime in Lima, Peru (where I am from), in the early ’90s. The second short story was about an American former CIA agent who worked in Latin American countries under far-right dictatorships in the ’60s and ’70s. I decided to put them together, so that the young guy in the ’90s would be following in the steps of the older man, his father, trying to trace the crimes the old man had probably committed in Latin America decades ago.

However, my filmmaker friend went into politics (he is now prime minister of Peru), and I found myself with this whole idea and no vehicle for it. So I decided to turn it into a novel. The novel itself was written in three months, between May and July of 2016, here in Brunswick. The first version was chaotic and more than 1,000 pages long. After finishing that draft, I worked for a year on reducing it to some 650 pages.

What is it about?

The arc of the story goes from the youth of the older man, in 1930s Vermont, to his later life in the military, in the Korean war, then to his work advising dictators in Argentina, Chile, and Paraguay, where his main work is designing secret prisons (and killing Che Guevara), until decades later, when, in the early ’80s, his son decides to find out who his father was exactly and what crimes he possibly committed in Latin America.

Most of the novel involves the son retracing his father´s steps, traveling across Latin America and being increasingly unable to differentiate between his father´s immorality and his own sense of justice (he is like a marred avenger who tries to bring justice to his father´s victims, but often fails). The novel is also about madness and political violence, but is very playful and even humorous in the way the story is told, even the grimmest parts of it.

Carmen Boullosa, a very important Mexican novelist (who visited Bowdoin a couple of years ago), has described the novel as "a sort of Latin American version of the Arabian Nights," because of the hundreds of short stories intertwined with the main plot and the large number of subplots.

By the way, half of the novel takes place in Brunswick, and some of the main characters are Bowdoin professors—they are actually loosely based on some of my real-life colleagues, but I will not reveal who the models are! (They are certainly the good guys in the novel, though).

What was your inspiration for the book?

My motivation for writing it was, mainly, that I am interested in the different forms of political violence in Latin America, but also in the way they are linked to a more global violence, like the Cold War and American interventionism (but also the Latin American propensity to blame the US for all the region’s political and economic problems). I am also motivated, on the one hand, by an interest in father-son relations, the inheritance of morals, and the rejection of inherited morals; and, on the other hand, by an interest in the relationship between "high culture" and violence (both father and son are criminals in different ways, but they are also artists: one is a frustrated poet, and the other is a documentary filmmaker)

How does it feel to be nominated for this prize?

I am, of course, overwhelmed by being a finalist for this award, because it bears the name of Mario Vargas Llosa, a Peruvian novelist and Nobel Prize winner who was the first serious, adult novelist I read in my life (he also visited Bowdoin a very long time ago.) His books determined my vocation to be a writer and a professor of literature, so to be nominated for this prize is happiness itself for me.”