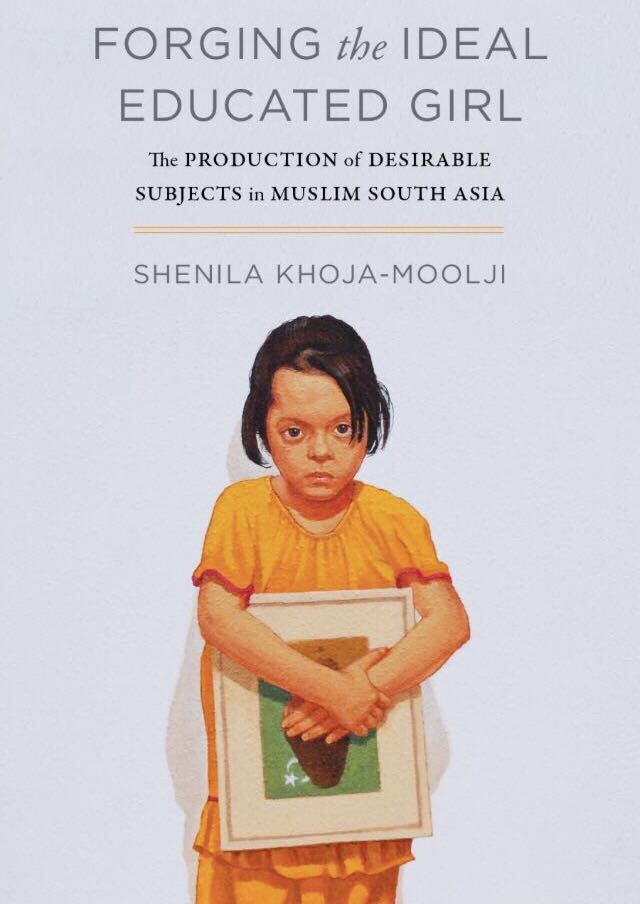

Book Launch: Shenila Khoja-Moolji’s ‘Forging the Ideal Educated Girl’

By Tom PorterIn her latest book, Assistant Professor of Gender, Sexuality, and Women’s studies Shenila Khoja-Moolji looks at how the education of Muslim girls in South Asia has consistently been regarded as a major bulwark against threats such as poverty, disease, and terrorism. Forging the Ideal Educated Girl: The Production of Desirable Subjects in Muslim South Asia (University of California Press, 2018) traces the figure of the “educated girl” to examine the politics of educational reform and development campaigns in the region.

In her latest book, Assistant Professor of Gender, Sexuality, and Women’s studies Shenila Khoja-Moolji looks at how the education of Muslim girls in South Asia has consistently been regarded as a major bulwark against threats such as poverty, disease, and terrorism. Forging the Ideal Educated Girl: The Production of Desirable Subjects in Muslim South Asia (University of California Press, 2018) traces the figure of the “educated girl” to examine the politics of educational reform and development campaigns in the region.

“I started thinking about this convergence on the figure of the girl in international development policy and practice, particularly brown and black girls, and how they are represented in a number of recent campaigns,” said Khoja-Moolji at a recent book launch event on campus. She mentioned a number of nonprofits, aid agencies, and international programs—groups like The Girl Effect, Let Girls Learn, and Global Girls Alliance—and how they portray girls as not only being threatened by issues like poverty, disease, and terrorism but also as having the potential to resolve these very problems.

“In this formulation, education emerges as the primary social practice that can help girls reshape and reinvent themselves into ideal subjects,” she said. To make her point, Khoja-Moolji pointed to an image from The Girl Effect campaign that featured a brown girl in a school uniform, holding a pen as a weapon and attacking a monster with “poverty” written on it. The image illustrated the promise of education, she explained.

However, Khoja-Moolji argued that “in this formulation the burden of development and ending poverty is being shifted onto black and brown girls, without due consideration to how poverty is political and an effect of historical relations.” She also observed that “through these campaigns girls are called onto re-shape themselves into flexible labor for the neoliberal economy which elides critique of capitalist and racist exploitation that leads to displacement and dispossession in the first place.”

Khoja-Moolji also posed a number of questions to faculty colleagues: What kind of girlhood is being imagined? Which girls emerge as successful and which ones are marked as failures?

While researching the topic, Khoja-Moolji said she was “reminded that this investment in the girl as a savior who can inaugurate our society into a better future, is actually a recurring storyline: In the eighteen and nineteenth centuries we find Christian missionaries in South Asia, as well as a number of Muslim reformers and British colonial officers, also writing about women’s education, and how that could lead society into a different future.”

For her book, therefore, Khoja-Moolji said she decided to explore this figure of the educated girl over the last 150 years, from the context of colonial India and Pakistan—the subcontinent was part of the British Empire until 1947—up until the present day. “I wanted to see where this figure appears, how she appears, what kind of work she’s doing, and what kind of education she is expected to receive.” In the book, Khoja-Moolji argues that such advocacy in favor of girls’ education was often not motivated purely by altruism or idealism: it was more about preparing young females to be responsible and productive wives, mothers, Muslims, and members of society. In other words, it is about “producing the ideal subject.”

In The News

Professor Khoja-Moolji recently wrote two op-eds for The Express Tribune, an English-language daily newspaper based in Pakistan.

In one of them, she asks the question “What is Patriarchy?” She defines patriarchy as a “name given to a dynamic web of ideas, policies, laws, and social practices that bring male domination and privilege into effect.”

She argues that women are not naturally subordinate to men for any biological or religious reasons. “Instead, women are made subordinate through concrete practices that propagate through the state, family, and religious and societal institutions."

The other op-ed deals with the issue of foreign charities and sexual exploitation, with particular reference to a sexual abuse scandal recently uncovered at a chain of schools in Liberia run by an American charity. Khoja-Moolji wonders, “What can we do then to attract foreign capital and knowledge, but still ensure that our young girls and boys are safe and thrive?”

Khoja-Moolji elaborates on the role of government and defines the ethics that should inform such endeavors. She writes: "Feminist movement-building teaches us that if two sides engage with each other from a perspective of friendship then the outcomes are beneficial to both. Such an approach entails viewing the other not as a recipient of aid or service, but as a partner with whom one enters into a relationship of mutual dependency and care."