An Exhilarating Combination of Speed, Skill—and Aggression

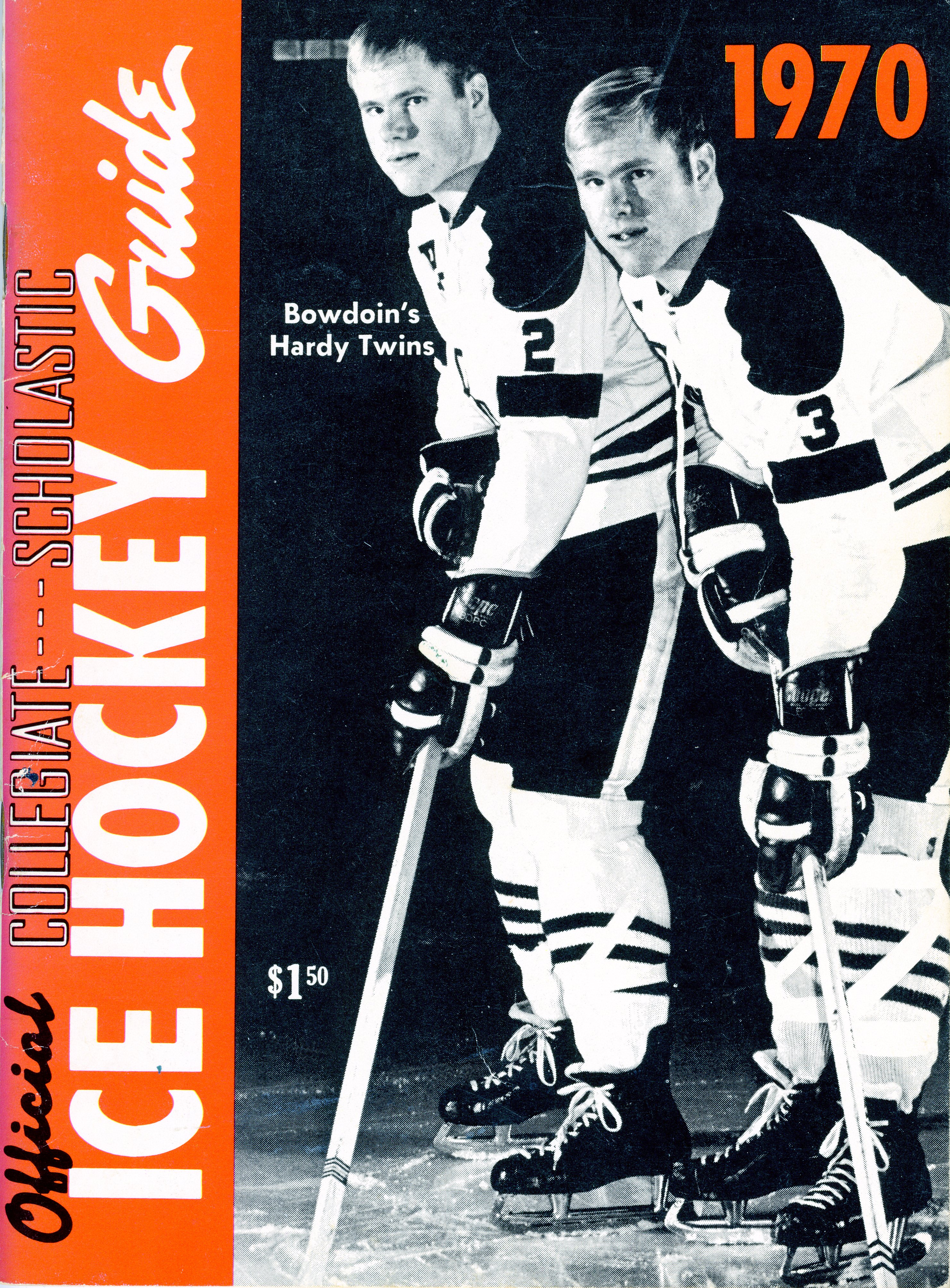

By Tom PorterNearly a half-century after hanging up his skates as a college athlete, Steve Hardy ’70 finds his passion for the sport of ice hockey remains undiminished.

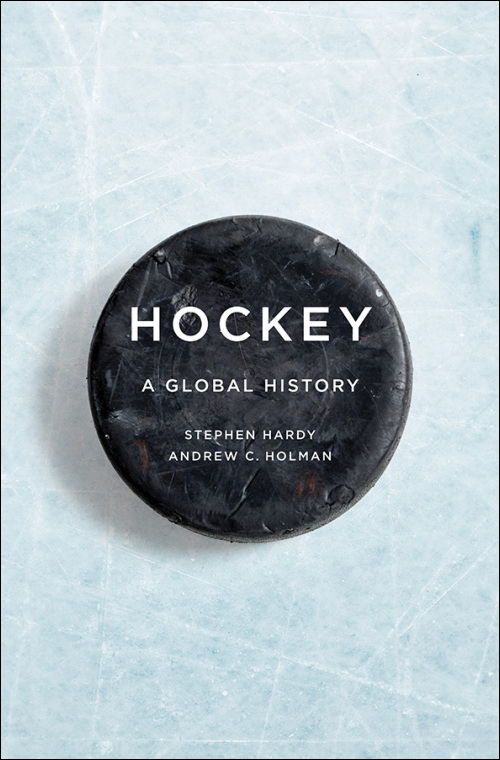

A retired UNH professor of kinesiology and history (affiliate), Hardy is drawing on twenty-five years of research to produce a book described as “THE monumental end-to-end history of the sport.”

Hockey: A Global History (University of Illinois Press) was published in November 2018 and coauthored by Hardy and Andrew C. Holman, professor of history and director of the Canadian Studies Program at Bridgewater State University, Massachusetts.

Ice hockey as we know it today, says Hardy, has its direct origins in Canada in the 1870s, specifically in Montreal. In fact, he points out, it was initially known as “Montreal hockey” to distinguish it from other, similar games on ice. “There is evidence going back centuries of games like ice hockey being played all over the world,” says Hardy. “In Europe, for example, you find games like bandy, shinty, and hurling being played.”

The Emergence of “Montreal Hockey”

The development of “Montreal hockey” came at around the same time that many sports started to develop a codified set of rules. In Britain, for example, says Hardy, the Football Association was founded in 1863 to govern soccer, while field hockey was codified in 1875. “It’s probable that these Montrealers tinkered with the field hockey rules, shifting from ball to puck, changing the shape of the stick and reducing the number of active players, and so on.” In 1886, he explains, a governing body was founded, the Amateur Hockey Association of Canada, and the game spread south to the US and then to Europe.

A seminal moment in the emergence of ice hockey as a global sport, says Hardy, was the Olympic Games in 1920 in Antwerp, Belgium. “One of the few facilities in Antwerp that made it unscathed through World War One was a roller rink that was converted to ice. By this time there were enough converts to this new sport to ensure that ice hockey and not bandy (which uses field hockey-type sticks and a small round ball) became the predominant Olympic team sport on ice. “If the bandy lobby had been stronger,” says Hardy, “ice hockey may not have become the global sport it is today.”

“Even though coaches impose systems, when you put that puck on the ice, sometimes you just can’t control what’s going to happen.”

—Steve Hardy

College Hockey

A significant portion of the book is dedicated to the growth of college hockey in North America. While American college hockey had been around for as long as the sport itself, Hardy says the period of great expansion was the 1960s and 70s, as more rinks opened up on campuses. “The NCAA hockey championship started in 1948 ,” he explains, “but growth was accelerated in 1966, when a second division was added. Until then, all schools were in the same division, which meant you could have colleges the size of Bowdoin, with less than a thousand students, competing for national standing against Michigan, with twenty-five thousand students.” Even after the establishment of a second division, Hardy recalls, Bowdoin would still often play against top tier teams like McGill and UNH, and would occasionally beat them.

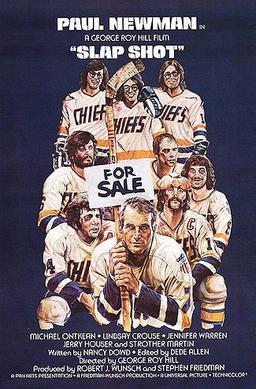

Slap Shot: The Bowdoin Connection

The cult ice hockey movie Slap Shot (1977), starring Paul Newman, has some surprising connections to Bowdoin College.The movie was written by Nancy Dowd, and is inspired by the experiences of her brother, Ned Dowd ’72, who played professional hockey after graduating from Bowdoin. Ned was Steve Hardy’s left wing on the 1969-1970 team.

After hockey, Ned pursued a career as an actor and film producer. In Slap Shot, he played the role of the notorious hockey player Ogie Ogelthorpe.

Bowdoin flourished in these years, says Hardy, and a lot of that was due to the legendary coach Sid Watson, who joined Bowdoin in 1959. He coached for twenty-four seasons, winning more than sixty percent of his matches and guiding the team to four Division II titles in the 1970s.

“One of the things that marked Sid out as a great coach,” says Hardy, “was the level of organization and attention to detail he brought to the game. This was in part due to his gridiron background and the fact that he had been an NFL player, having played for both the Steelers and the Redskins.” Hardy says Watson, like many young coaches who arrived during the 1950s, wanted to bring more “system” to the game, whereas the approach of previous coaches had been more laid back.

Steve Hardy and his twin brother, Erl, were both regular fixtures on the team under Watson during their time at Bowdoin. “Our practices were very systematic,” he recalls, “with multiple approaches to fore-checking and to power play. Sid was a wonderful motivator,” he adds, “using sarcasm and dry wit to inspire his athletes.” As well as selecting teams, Watson also proved very good in his choice of his successor, the hand-picked Terry Meagher, who went on to be even more successful than Watson, says Hardy.

For the Love of Hockey

Even though Hardy enjoys other sports—he’s a fan of Brighton & Hove Albion soccer club in England for example—there’s something about ice hockey that lights a fire in his soul. “For one thing, there’s the speed. You could never travel as fast on foot as you do on skates. And when you combine this speed with skill, science, and physical contact, it’s exhilarating. Even though coaches impose systems, when you put that puck on the ice, sometimes you just can’t control what’s going to happen. All this is what makes hockey unique.”

Hardy will be on campus presenting a talk called "Bowdoin and the Wide World of Hockey: 1880-2010" this coming Saturday (1/26) ahead of the Colby game. The event will be at 3:30.

A Global History of Hockey (University of Illinois Press, 2018) was recently reviewed on local radio station WZON.