Students Get Up Close to, and Behind, Museum Art

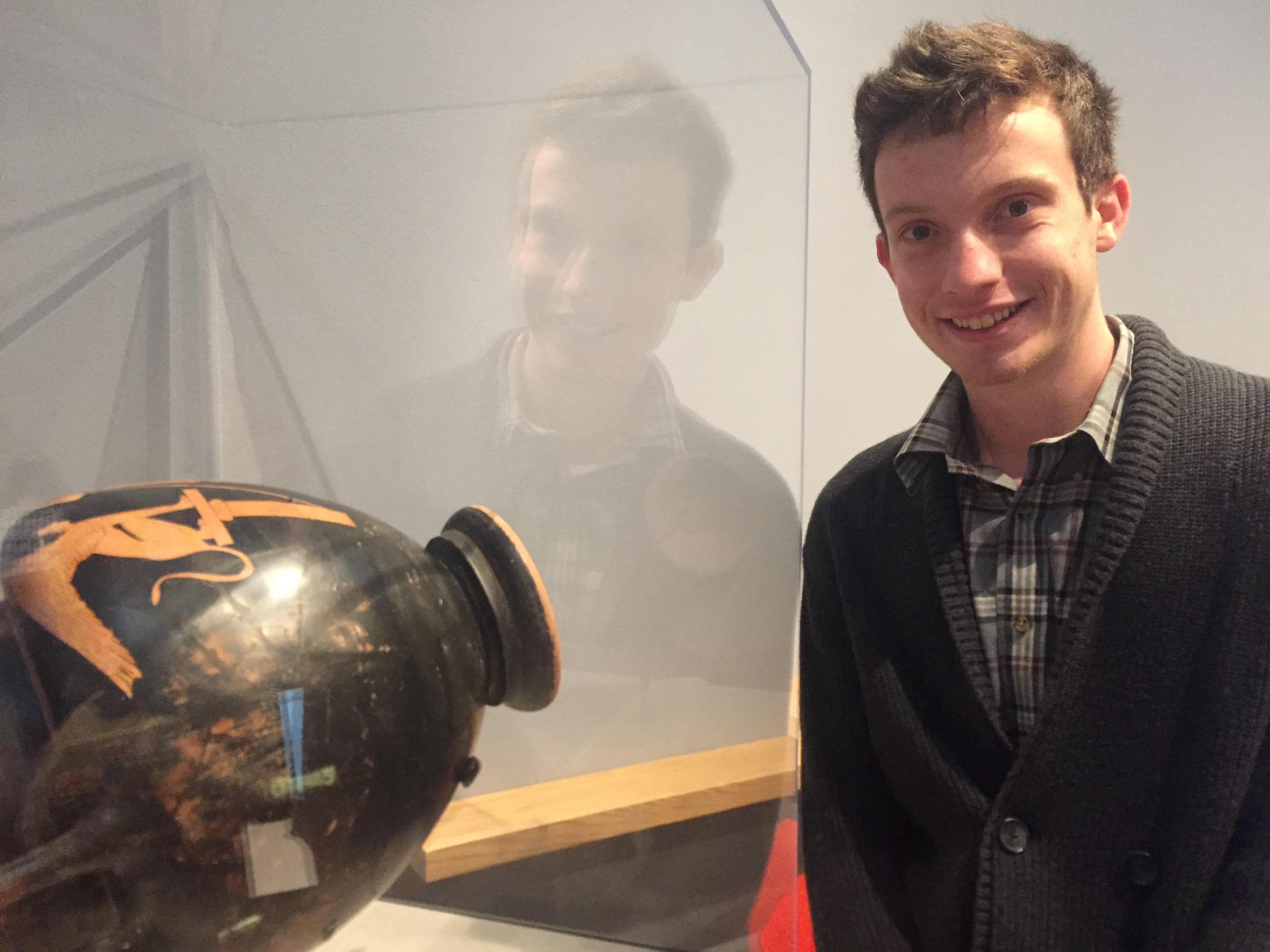

By Rebecca GoldfineWith white gloves hanging halfway out of his pocket, Bowdoin Museum of Art fellow Sean Burrus greeted a small group of students in the Museum's Zuckert Seminar Room. Gesturing to the artworks set up around the room, he told the students that this was a great opportunity to observe rare pieces up close.

But he followed this with a gentle plea: so please, he asked, could students try not to breath too much hot, moist air on the ancient tempera paintings?

With this mild injunction in mind, the students in the visiting Arabic class gathered around the intricate illustrations. Their professor, Pamela Klasova, had asked them to translate the classical Arabic script inscribed on some of the medieval manuscript pages.

Klasova’s class is learning modern standard Arabic, but there is enough similarity between the two forms of language that the students were able to make out some of the old words. They read aloud to their partners about alchemical magic and recited lines of Koranic verse.

Klasova’s course is just one example of how faculty are using the museum’s collections for teaching. Art history, German, French, religion, digital and computational studies, archaeology, and history classes have all scheduled visits to the art museum this semester.

After soliciting input from professors on what they'd like to share with students, Burrus—who is the Museum’s current Andrew W. Mellon Postdoctoral Curatorial Fellow—arranges to have pieces from storage carried up to the Museum classroom.

Because only a fraction of the Museum holdings are exhibited in public galleries at any given time, this practice is a way for students to explore more of its 33,000 objects, drawings, sculptures, photographs, and paintings. Or as the Bowdoin Offer promises, to “count Art a familiar friend.”

So far this semester, the Museum has made more than 1,030 pieces of art available to students in thirty-three different classes, from twenty-two academic departments.

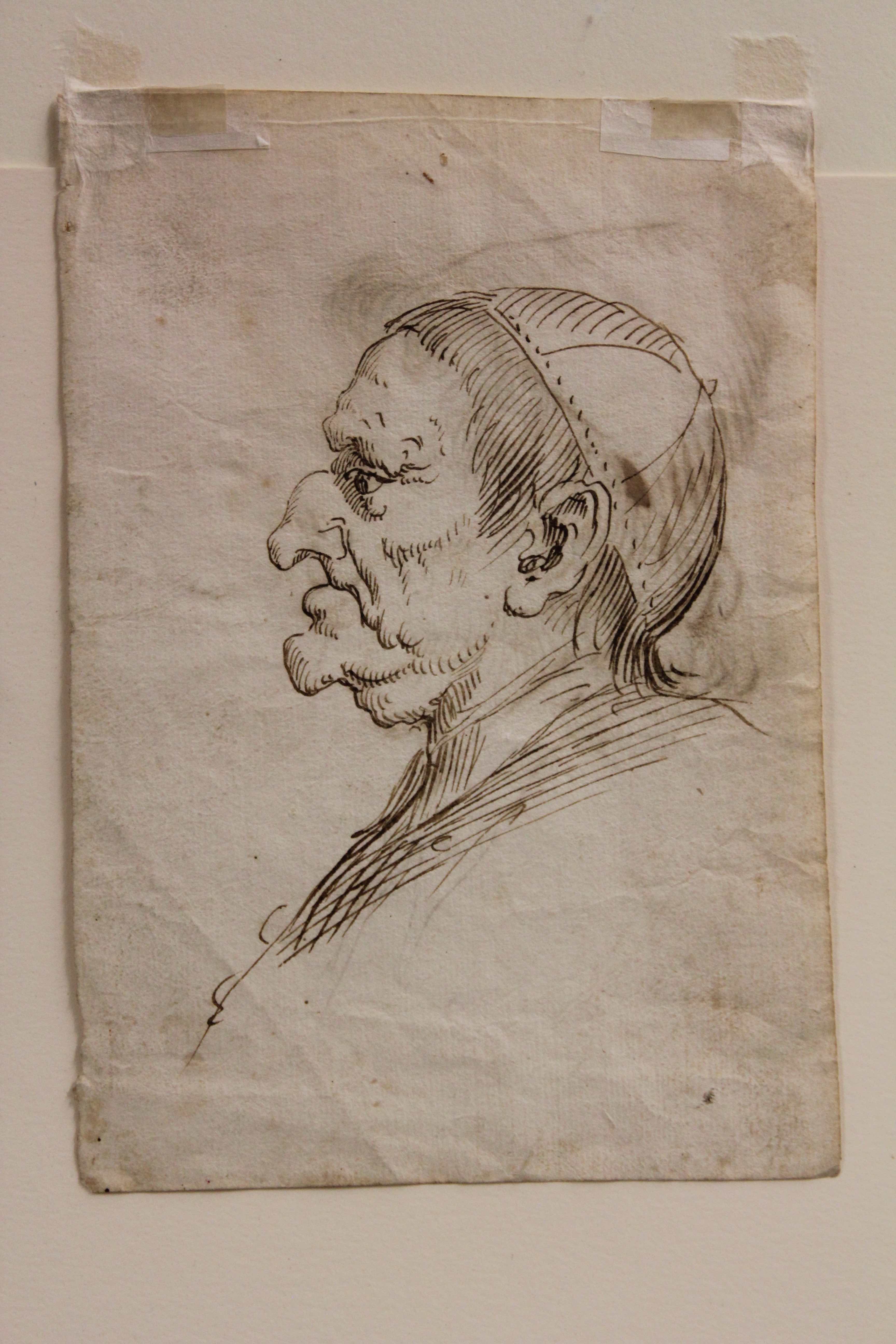

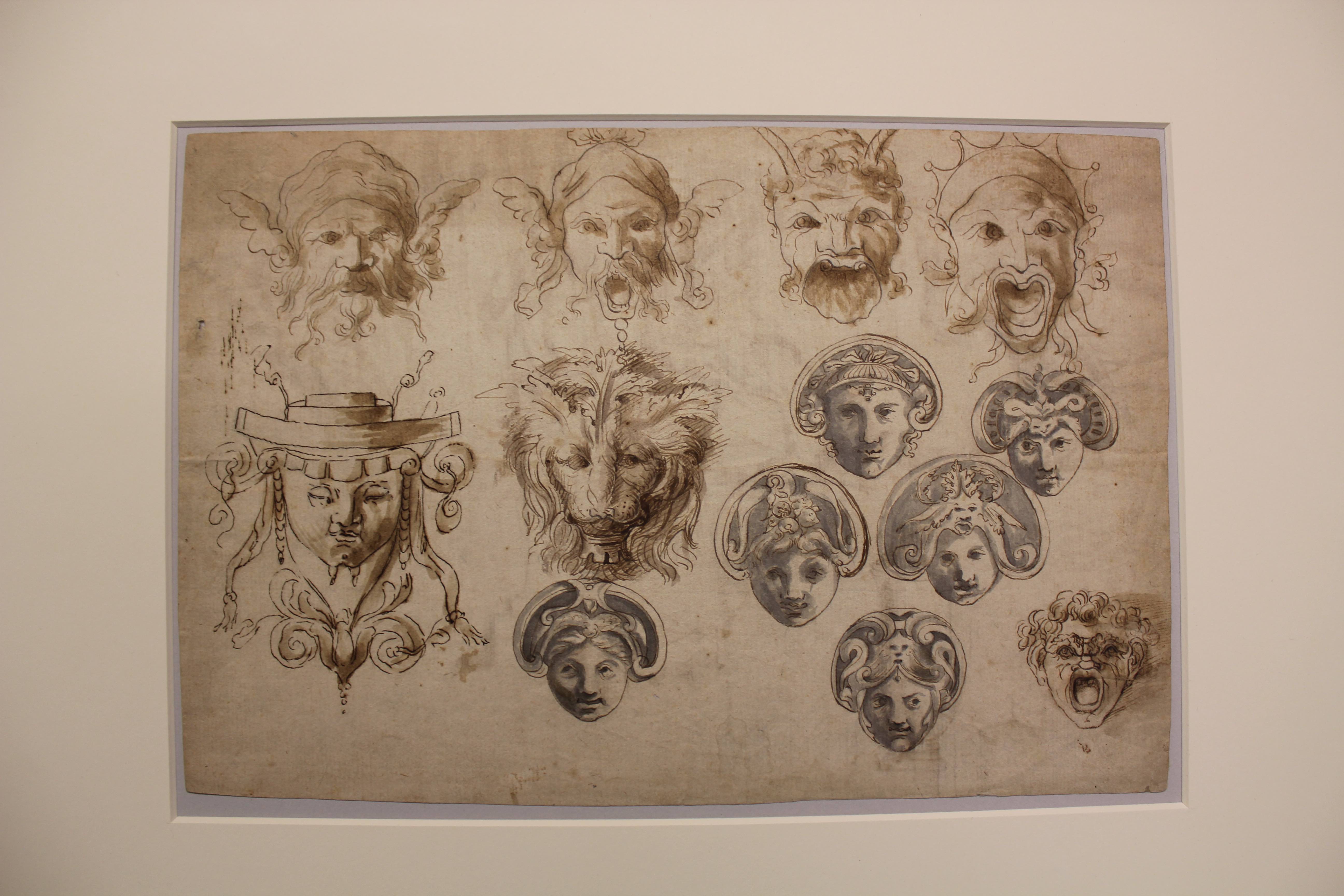

On another day, students in professor Susan Wegner’s upper-level art history class, Leonardo da Vinci and Michelangelo: Science and Art through Drawing watched and waited, Burrus carefully turned over delicate drawings, some of them depicting grotesque faces and unflattering caricatures. In about half the cases he revealed, to exclamations of delight from the onlookers, a hidden sketch on the back. In seventeenth-century Italy, artists made efficient use of paper, practicing on every available part. They'd even sometimes get an idea from the ink that would bleed partially through the paper, according to Wegner.

Wegner asked her students to analyze the drawings, looking for signs that they might have been made by a master or an apprentice, or whether a collection of figures on one piece of paper may have been sketched by more than one artist. “Is there any inheritance from Leonardo da Vinci from these things? Does this represent one artist’s collection of ideas?” she prompted. "What can we tell about the paper, how was it made?"

Language and art

Burrus said it’s fairly common for language classes to visit the museum. Talking about art, he noted, requires language learners to dig deeper for descriptive vocabulary and ways of articulating abstract thoughts.

The desire to learn a new language also reflects a wish to discover another culture. “Language is a tool to be a part of a culture and participate in it,” said Pamela Klasova, Bowdoin's Andrew W. Mellon Postdoctoral Fellow in Arabic, who brought her Advanced Arabic class to look at art from Islamic lands. At the Museum, there is a trove of resources for them. “They can go and talk to specialists about real objects, real pieces of other cultures,” she said.

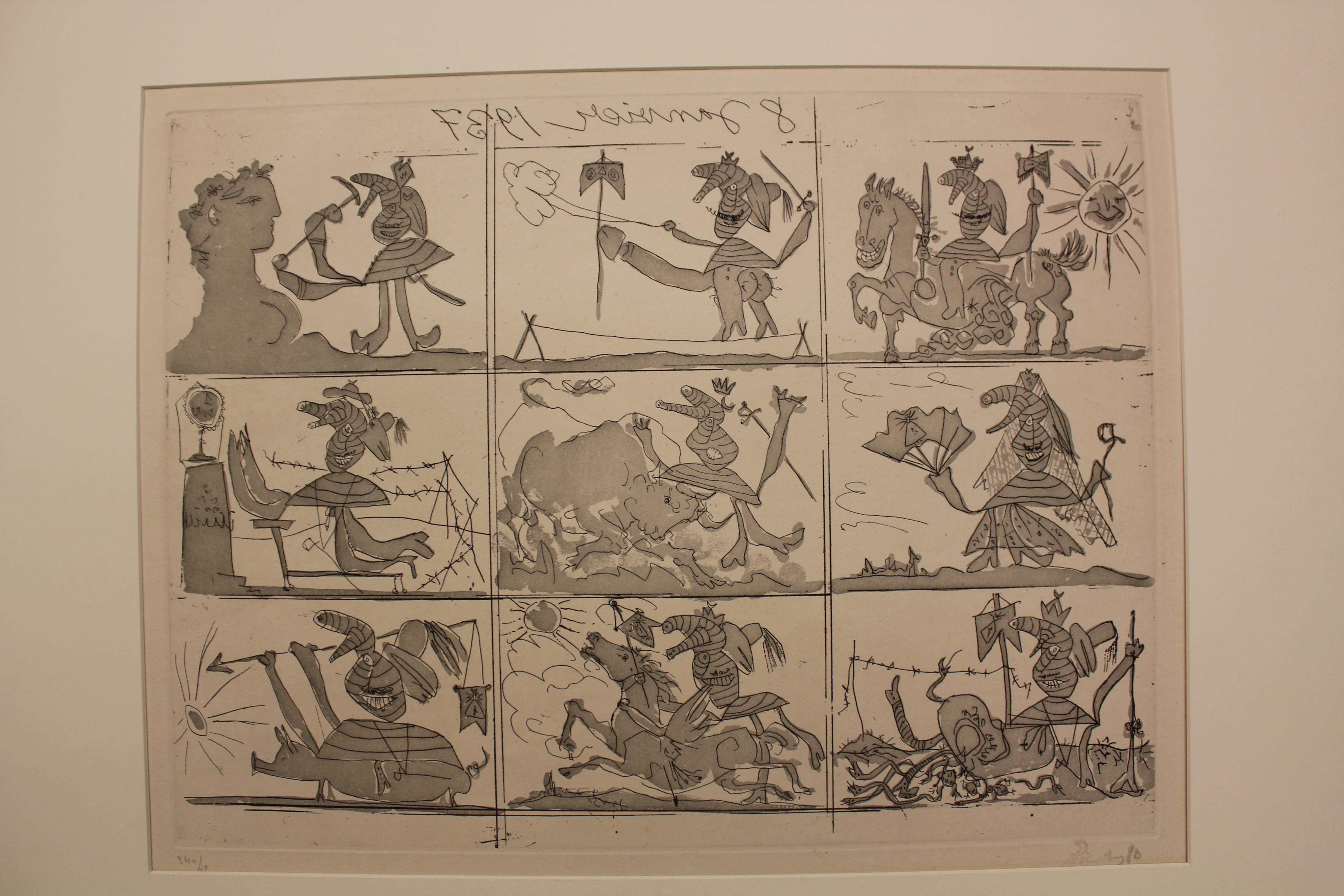

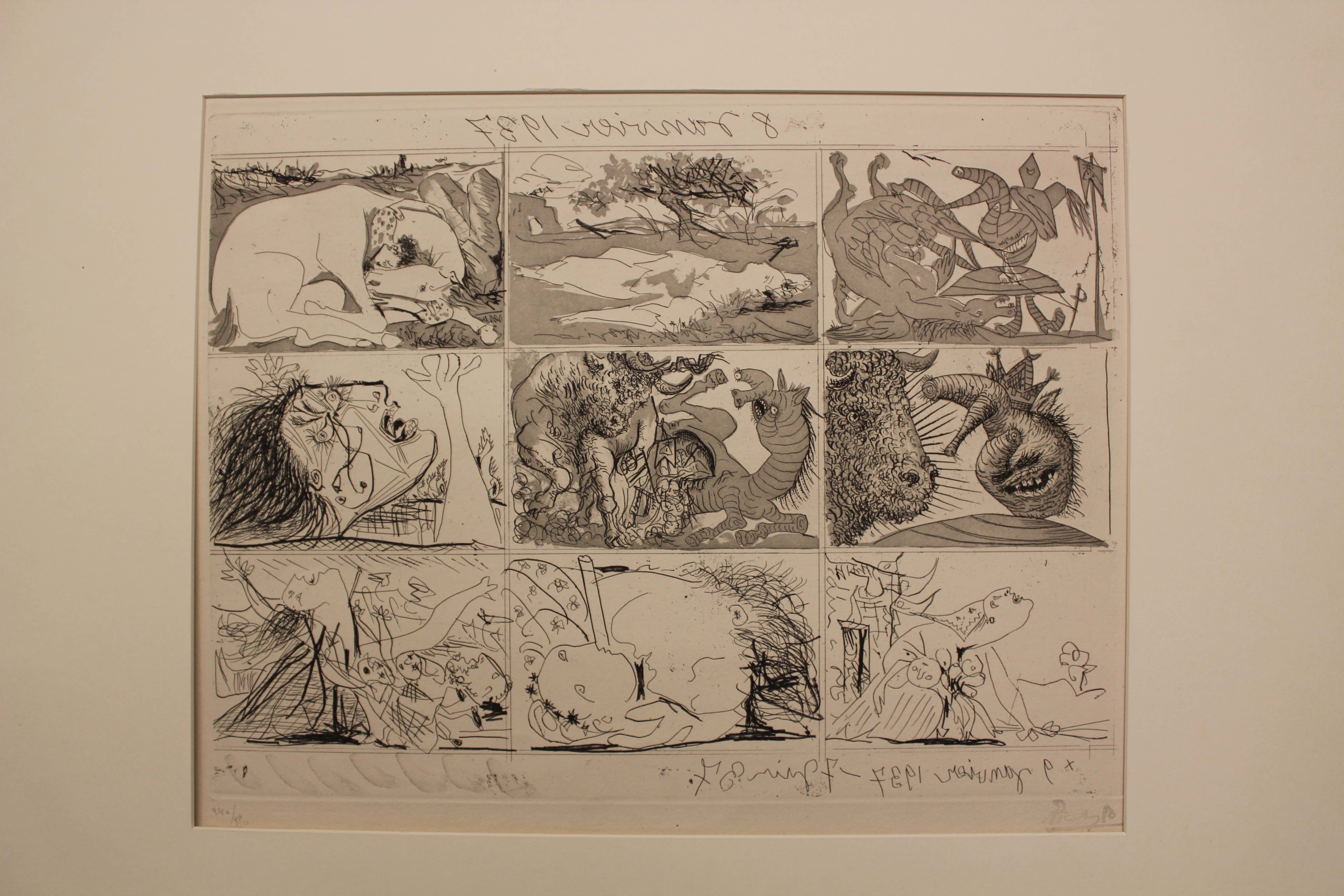

Associate Professor of Romance Languages and Literatures Carolyn Wolfenzon also brought her Advanced Spanish class to the Museum this semester to look at the 1937 Dream and Lie of Franco, by Pablo Picasso, an etching and aquatint on paper.

"I wanted to add some visual activity so the students can have a different connection with the topic on top of narrative, poetry, essay and film," she explained.

Angelica Peña, who is part of Wolfenzon's class, said that the print was "one of the ways Picasso chose to enter the political world." She continued: "Lie of Franco satirizes the Spanish Civil War, specifically the dictator at the time, Francisco Franco. Franco is caracaturized with a disfigured and elongated set of eyes and nose and rounded hips. He illustrates a desire to conquer and kill."

Storytelling, mythology, and art

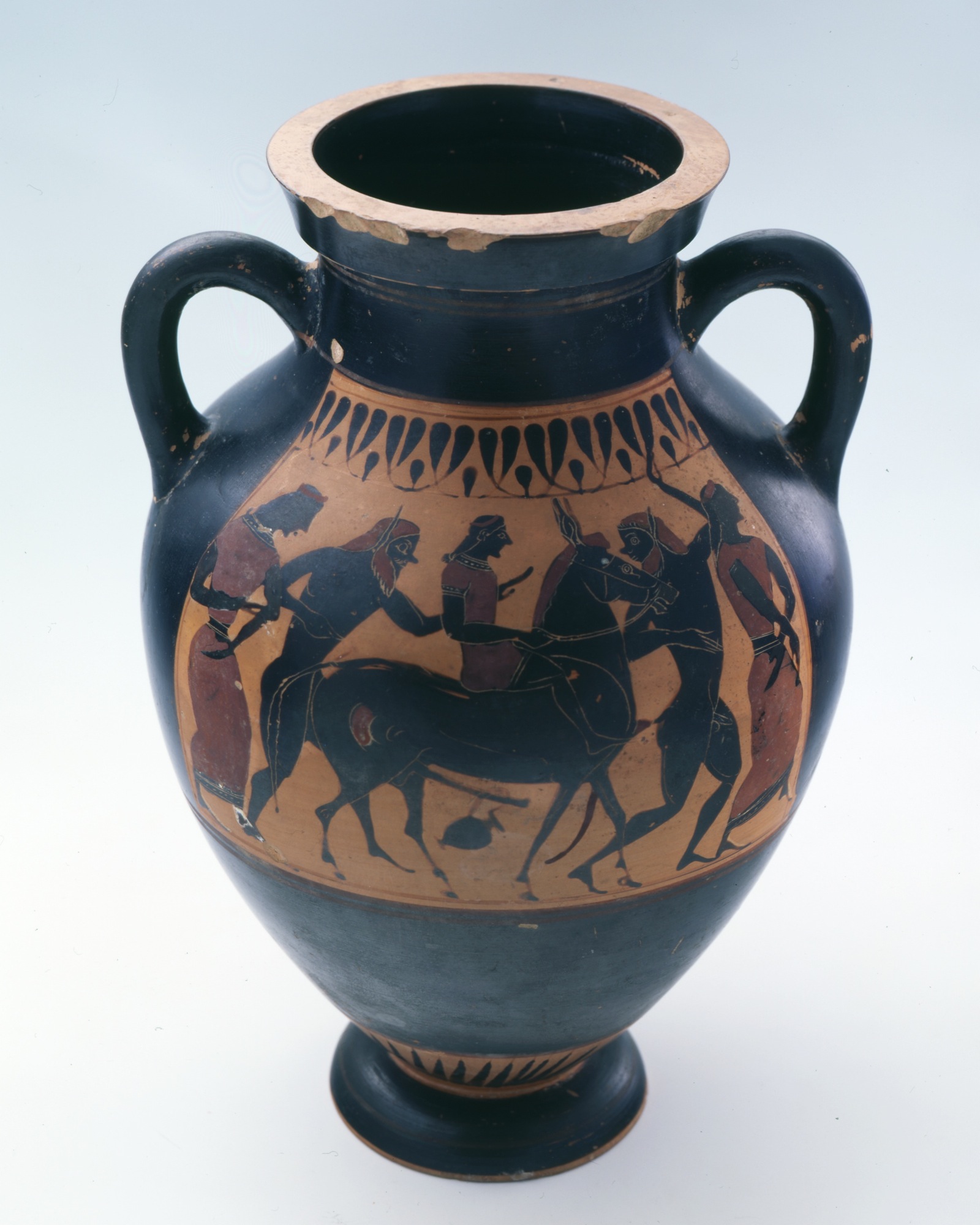

Like all first-year seminars, Associate Professor of Classics Jim Higginbotham’s class, The Archaeology of Ritual and Myth in the Ancient Mediterranean, is designed to develop first-year students’ writing skills. His students also get the added bonus of checking out the many ancient Greek and Sicilian ceramics in the Museum. Higginbotham, who is an Associate Professor of Classics on the Henry Johnson Professorship Fund, is an expert on ancient Greece and Rome.

Standing in the midst of ceramics on one recent visit to the Museum classroom, he said, “The seminar is an opportunity to let first-year students know what the Museum has to offer, and to get behind the scenes.”

Tom Hornbeck ’22, who decided to write a paper on the Museum's Black-Figure "Little Master" Band Cup, a sixth century BCE Greek ceramic, said he was amazed by the access students have to invaluable pieces of art. “We’re in a room with crazy ancient artifacts,” Hornbeck said. “It’s shocking to be so close to them.”

Click through the slide show below to see the pots students selected to research.