From the Perspective of the First Mainers: Workshop Teaches Wabanaki History

By Nicole Tjin A Djie ’21

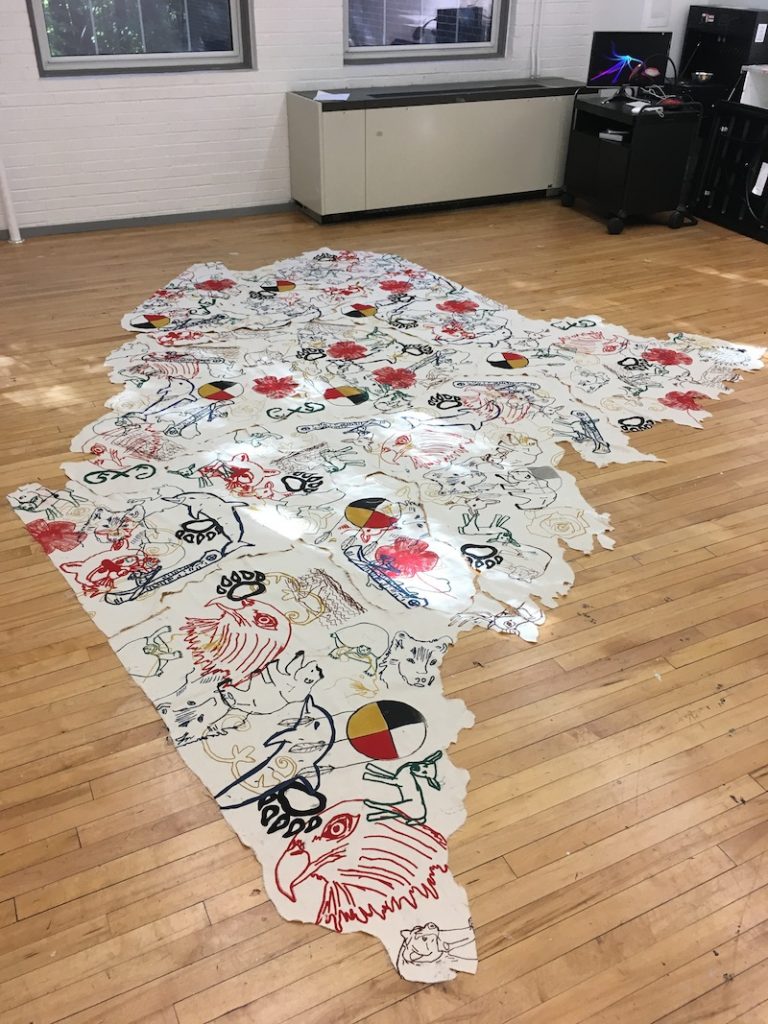

The Wabanaki map literally at the center of a recent Bowdoin workshop was imprinted, like a fabric mosaic, of images integral to the history of the Wabanaki people and their culture: a red eagle, a tri-colored dream catcher, fish, and mammals.

Over the course of the workshop, the Wabanaki map—the colorful storyboard in the middle of the room—was folded up and broken apart several times, representing the fragmented nature of Wabanaki history. By the end, the pieces were rolled out and put back together, as if to symbolize the resilience of the Wabanaki up to the present day.

Diana Furukawa ’18 helped facilitate the recent afternoon event in the Edwards Center for Art and Dance with Maine-Wabanaki REACH, a nonprofit engaging non-native people in restorative justice for the Wabanaki. The Wabanaki refers to five nations—the Mi’kmaq, Maliseet, Passamaquoddy, Abenaki, and Penobscot—who are from the Northeastern part of the country, including Maine.

Furukawa currently works at the public library in Millinocket, Maine, helping with community-led grassroots revitalization efforts in the Katahdin area. To bring the Wabanaki event to Bowdoin, Furukawa partnered with Barbara Kates, REACH’s community organizer.

“We are working toward truth, healing, and change with educational programs that teach how the process of colonization happened and continues to happen here,” said Kates.

REACH describes the workshop, which it holds throughout the state with different groups and at different venues, as an “interactive story-telling experience.” A blend of reading, writing, and historical exploration, the event deconstructs colonial history to illuminate the relationship between European settlers and Maine’s indigenous people.

The reading, which comprised the majority of the workshop, had each student share a part Wabanaki history from a first-person narrative. By interacting with one another and the printed map, participants engaged with the physical space, bringing the past to the present in an active, physical way.

Furukawa said this type of first-person storytelling can be a more emotional experience than simply learning about history from classes or books. “Bowdoin is on indigenous land and you can say that, but what does it mean to feel that?” she asked.

Maine’s Truth & Reconciliation Commission on native child welfare had previously recommended that the workshop be held at Bowdoin, to raise awareness that its records are held in Bowdoin’s Special Collections.

Whether it be through workshops or other channels, change can occur if non-native communities work together with the Wabanaki, Kates said.

At Bowdoin, this work continued when Furukawa visited Associate Professor of Art Carrie Scanga’s Printmaking I class the following week. Together they made a new map with the same child-inspired silk-screen designs. “Wabanaki REACH is trying to create many maps so that the workshop can more easily spread,” Furukawa said.