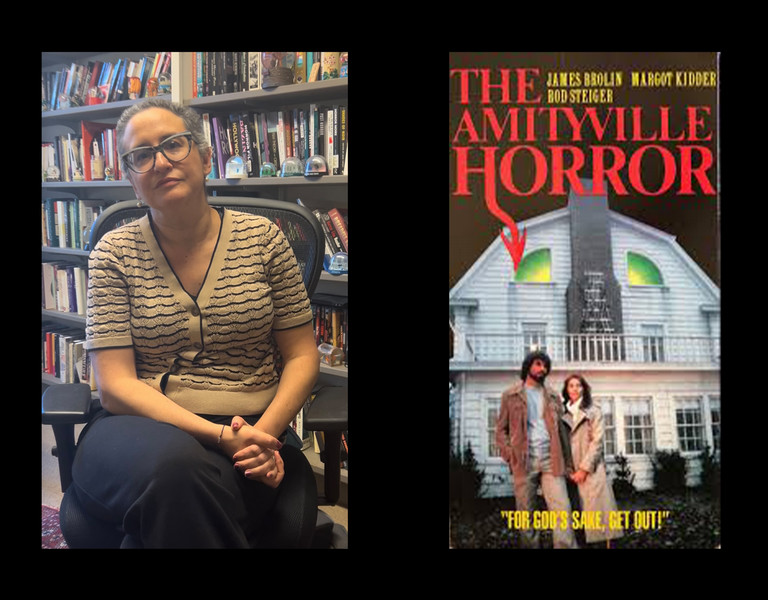

Humans, Animals, and Modern Literature

By Tom Porter

By comparing the works of twelve different authors, she examines the concept of “creatureliness” – which refers to the characteristics shared by humans and animals – and how that has changed in literature over recent years.

Thompson argues that creatureliness has been an intensely millennial preoccupation, but in two contrasting forms – one leading up to the turn of the millennium, and the other appearing after the tragic events of 9/11.

What prompted you to write this book?

My teaching and research covers a lot of philosophy, and an important question being asked by philosophers right now is, “What’s the difference between animals and humans and how do we define that?” It’s an issue reflected in many contemporary novels, where we see the human facing off with the animal. One well known example is Life of Pi, where a boy is stranded at sea, at first with several animals, but supposedly survives alone with a Bengal tiger. There are many other examples from authors all over the world, and depictions ranging from traveling circuses to problematic animal conservation efforts. It’s a rich topic.

How has the relationship between humans and animals evolved in literature?

There’s quite a contrast between earlier literature and more modern works. Novels that were written during the second half of the last century often portrayed fantastically hybrid creatures that possessed such supposedly exclusive human capabilities as linguistic expression or philosophical thought. We see this in Angela Carter’s Nights at the Circus, where performing apes subject a human clown to scientific analysis, or in Barbara Gowdy’s The White Bone, where elephants discuss what it means to live in a world depleted of former systems of meaning.

The way animals were treated in novels changed quite noticeably after the events of 9/11, as animals became more frequently used as stand-ins or proxies for humans, and this is what my book looks at: comparing pre- and post-9/11 literature.

How did the approach of the millennium influence the treatment of animals in novels?

In the literature that intrigued me leading up to 2000, there was a desire among authors to move beyond anthropomorphism and think about the animal standing for itself, not as an allegory or a symbol for humans. Additionally, we all had these fears about the approach of the new millennium, fears that we had depleted the planet and that our technology was going to rebel against us. We became self-critical as a species, as if we were moving toward some sort of judgement day when our mistakes would come back to haunt us. A great way to describe this was to compare us to other species, so this became a great topic for novelists. Animals were often compared favorably to humans, as creatures that we can learn from. This is reflected in novels like The White Bone, in which elephants have not only cognitive and linguistic capabilities similar to ours, but also precognitive apprehensions of the future and telepathy, abilities most of us wouldn’t claim to have.

What effect has 9/11 had on the human-animal relationship in literature?

After 9/11, we felt this failure of society and started to ask worrying questions like: “What if governments aren’t working and nation states aren’t coherent?” We were in that “law of the jungle moment,” where we feared eruptions of terrorism could happen anywhere, anytime. When thinking about this return to a state of nature, the animal is such a great focal point for discussing what is wrong with the human condition. Two novels about tigers are great examples. Life of Pi closes with the suggestion that no animals were truly present on the lifeboat, that this was a cover story for real events concerning human brutality and survival. And Amitav Ghosh’s The Hungry Tide implicitly argues that there is no responsible way to think about tiger conservation in the Sundarbans region of South Asia without also remembering a tragic yet state-sanctioned massacre of human refugees that took place there. Ghosh insists we think about sustainability in the broadest terms for the sake of both humans and animals, but some readers worried that tigers got shorter shrift in his treatment of the region’s issues. We can see this, though, as part of a post-9/11 trend in which human tragedy cannot be restricted to a background, even when novels seem to be about animals.

How is the book structured?

It’s four chapters plus an introduction and a coda. It covers novels written by twelve authors from across the globe and set in diverse locales – Europe, Asia, Africa and North America. I often discuss pairs of novels, written on either side of 9/11, but sometimes the book entailed my discussing a cluster of texts.

Do you have any pets?

A lot of pet rocks, but perhaps other creatures to come.