The History of the Breakfast Sandwich and the Politics of Hummus

By Rebecca Goldfine

For Clayton Starr, the breakfast sandwich is not just a tasty way to start the day (and the only thing he says he knows how to cook). It is also imbued with all sorts of emotional significance. So this spring, when he was asked to write about food in his English class, Advanced Narrative Nonfiction: Writing about the History, Culture, and Politics of Food, he decided to investigate the origins of his beloved breakfast.

As Starr began to dig into its history, he stumbled upon some fairly wild theories. “…After my research, I developed two theories on the breakfast sandwich’s evolution. 1) Cowboys and explorers transformed old ingredients to hide the taste of bad eggs. 2) Chinese railroad workers re-created an omelet dish called egg foo young.”

Another student in the new class, Maia Coleman ’20, wrote about hummus, uses the creamy spread as a base from which to explore a bit of family history and the significance of the food item within the fraught socio-political context of the Middle East. “The hummus had depth,” she describes a moment in one passage. “It tasted bright yellow, like the humming, honking Tel Aviv streets…As I stared down at the familiar colors of the sandwich — delicate brown, hot red, vibrant green — I thought about where it had come from. I thought about my grandmother grinding chickpeas in her apartment…I thought about the soldiers with machine guns who had waved our Birthright tour bus through the border of the West Bank. I thought about my brother in his olive green IDF uniform.”

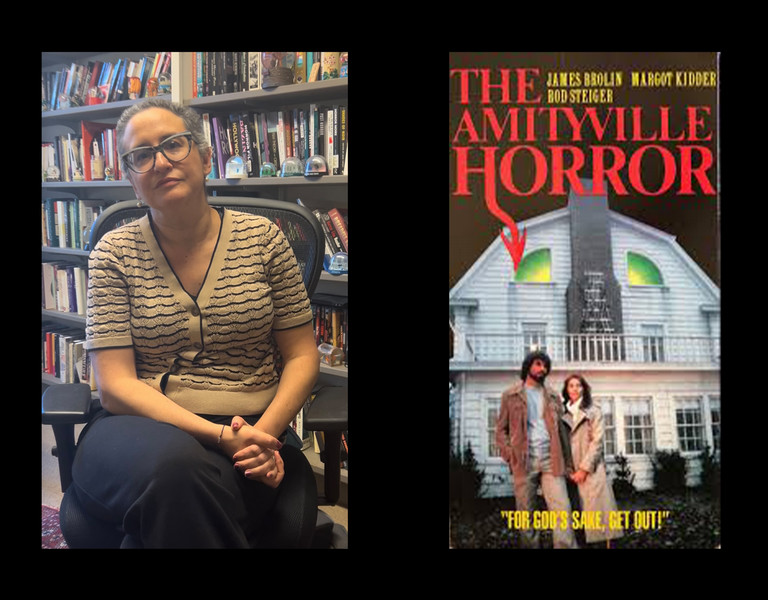

Jane Brox, a visiting professor who taught the food writing course, said her intention with the class was to encourage students to develop their writing style by focusing on a subject they cared about. “I wanted the students to learn how to create a voice on the page that could both accommodate a personal narrative and research,” she said.

Her reading assignments included Henry David Thoreau’s essay, “Wild Apples,” (“…his love of the subject is on every page,” Brox said) and the poems, “Ode to Tomatoes,” by Pablo Neruda, and “Oysters,” by Seamus Heaney. “I included some poems because I wanted students to work on their descriptive powers,” she explained.

Brox, who lives in Brunswick, Maine, has published several books, three of them on farming, so was comfortable with the course’s theme. “I felt very much at home with the subject,” she said. “And I thought, well, no one else here has offered a class about writing about food.”

Writer Jane Brox assigned a long list of reading in her advanced narrative nonfiction class this spring. Some are listed here:

- “How Did Macaroni and Cheese Get So Black?” from Adrian Miller’s book Soul Food

- “Edna Lewis and the Black Roots of American Cooking,” Francis Lam

- “Out of the Kitchen, Onto the Couch,” Michael Pollan

- “How Wolfe’s Neck Farm is Combating Climate Change,” Mary Pols

- Epitaph for a Peach, David Mas Masumoto

- “What’s True About Pho?” Rachel Khong

- “The Eaters and the Eaten,” John Berger

Excerpts from Maia Coleman’s Chumus ve’pitah

“Hummus is a Middle Eastern invention — there is no question about that — but with very few and very simple ancient ingredients (chickpeas, tahini, garlic, oil, lemon, salt) and much regional variation, it is difficult to attribute the delicacy to any particular nation. In her article, “Who Invented Hummus,” BBC Travel journalist, Diana Spechler, examines the politics of the food, arguing that “for many, the question of where hummus comes from is absolutely a matter of patriotism and identity.” A comically convenient metaphor for the politics of the region, Spechler claims, “hummus is a Middle Eastern food claimed by all and owned by none.’” While the intricacies of the “Hummus Wars,” as this particular debate is so earnestly dubbed, remain murky, Syrians, Egyptians and Israelis alike can all agree that since its conception, the food has evolved quite a bit. That is, the chickpea mixture of the Middle East has traveled a long way to become “hummus” in the form that we Americans most often see it: mass produced, lining the aisles of grocery stores in little plastic tubs.

The answers to the hummus question and the political debate to which it is so intimately tied do not seem like they will be resolved any time soon. And I certainly will not claim to have any solution that might put an end to the age-old Hummus Wars. What I present instead is my hummus, an account of the food that has given so much flavor to my family life.

So, for my admittedly biased purposes, the word for the real hummus is the one flung emphatically across the kitchen before dinner at my Israeli grandmother’s house, the one elegantly repeated by my bilingual mother to a clerk in the aisle of Fairway Market, the one that taught me to reach back deep into my throat for that glorious, guttural chhhhhh sound: the Hebrew word, חומוס (chumus).”

Excerpts from Clayton Starr’s From Cowboys to Oceans: A Breakfast Sandwich Story

“I had a loving family, a private school education, my health, and three meals a day. But I walked alone mostly, tried to pay attention in class, and I missed my three older brothers who had gone to college and beyond. I was never depressed but often heavy. Like an over-easy gone too long, I was hazy over the head, trying to let something dense go. I’m not sure when, but my mom saw this in me, and she started to do something beautiful. Every morning, she’d make me a breakfast sandwich.”

“And where does the Chinese theory fit into our Wild West landscape? … It’s no secret that the American transcontinental system would not have been possible without the labor of Chinese immigrants. According to cookery legend, the same could be said of the breakfast sandwich. Out of hunger and homesickness, worker gangs tried to re-create a Chinese omelet dish called Egg foo yung. Like American omelets, Egg foo yung features a choice of meat: shrimp, lobster, chicken, pork or beef. And it’s got veggies: bamboo shoots, bean sprouts, cabbage, spring onion, mushroom and chestnuts. However, at 19th century American railheads, most of the traditional ingredients weren’t around. Like the Cowboys and Co., Chinese immigrants had to use what they could. Green pepper replaced bamboo shoots. Shrimp turned into ham. And probably missing again was cheese! Between some bread, this meal offered workers a hand-held touch of home. With ease, they could carry their bite, keep working and be across the world. I love the poetry in that, too. If I ever left home for good, I think I’d also make a lot of breakfast sandwiches.”