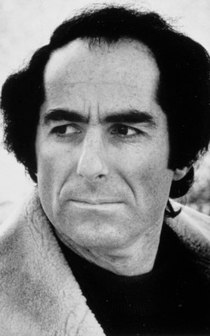

English Professor Marilyn Reizbaum Remembers Author Philip Roth

By Tom Porter

Harrison King McCann Professor of English Marilyn Reizbaum shares her thoughts on the author Philip Roth, who died on May 22, 2018, aged eighty-five. An expert on modernism, Reizbaum teaches courses on Jewish cultural studies, among other things.

I was shocked and saddened to hear that Philip Roth had died yesterday. Roth is one of the great writers in the English language. I am not going to qualify that statement by nationality, ethnicity or period, though one might do that in order to locate the work, which is certainly modern, American and Jewish. Roth himself felt diminished by the label of Jewish -American or by being grouped with other writers who were and whose subjects were American and Jewish, like Saul Bellow and Bernard Malamud. Roth wrote about almost nothing else, except when challenged as in the case of When She Was Good, (1967) which he wrote in response to critics of Goodbye, Columbus (1959), who confined him to the topic of Jewishness. An homage to Henry James, it is a great novel, and nothing Jewish to be found anywhere in it. That detour aside, one should recognize that part of Roth’s enormous contribution to literature resides in making the Jewish subject central. In asking, in the best modern way, what qualifies as worthy for a novelist’s focus. Roth’s prolificacy—he wrote twenty-seven novels, numerous short stories, essays—and his virtuosity make him one of the great writers. Full stop.

I have been hearing from several former students this day because of the work we did together on Roth. In 2006, I inaugurated the Modern Novel course and decided to do that by tracing developments in literary form solely through the work of Roth’s novels. From realism, surrealism (Goodbye, Columbus, 1959), psychological novel (Portnoy’s Complaint, 1969), autobiographical novel (The Facts, 1988), modernism (The Ghost Writer, 1979), postmodernism (The Counterlife, 1986), to the alternative history of ThePlot Against America (2004). The Library of America had just determined to produce Roth’s collected work, but this accolade was not initially enough to persuade students of this approach. The work did. Since then, there is much to add: the American Trilogy for which he has become best known including The Human Stain (2000). Or his poignant threnody Everyman (2006).

Last year I gave a talk at the invitation of Bowdoin Friends about The Plot Against America, called “The Prescience of Philip Roth.” Roth had maintained that his novel was not a revisionist history or roman à clef, though it is read as counterfactual. I had always thought of it as admonitory about the future, about how “it can happen here,” to riff on Sinclair Lewis. Indeed, I was making the case that his 2004 novel had something uncanny to tell us about our current moment. Or all too canny.

I think it’s important in this historical moment, particularly, to mention the charge against Roth of sexism and misogyny. It is deserving of debate. Roth was concerned with sex, sexuality, gender and was determined to be “shameless,” as he said in a 2014 BBC interview, in writing about taboo subjects. In a 2010 review of his final novel Nemesis, Leah Hager Cohen revisits her initial distaste for Roth on this basis, and comes to admire Roth’s “sheer energy, his unremitting investment in— Provocation. Interrogation. The feat of living. This a writer whose creative work lays bare the act of struggle.”

A struggle worth having.