MacEachern Book Studies Origins of Boko Haram

By Tom Porter

Scott MacEachern’s latest book—Searching for Boko Haram: A History of Violence in Central Africa(Oxford University Press, 2018)—sheds fresh light on the origins of the Central African Islamic terror group. MacEachern, an anthropology professor with more than three decades of experience researching the archaeology of the Lake Chad Basin, came upon the subject more by circumstance than intention.

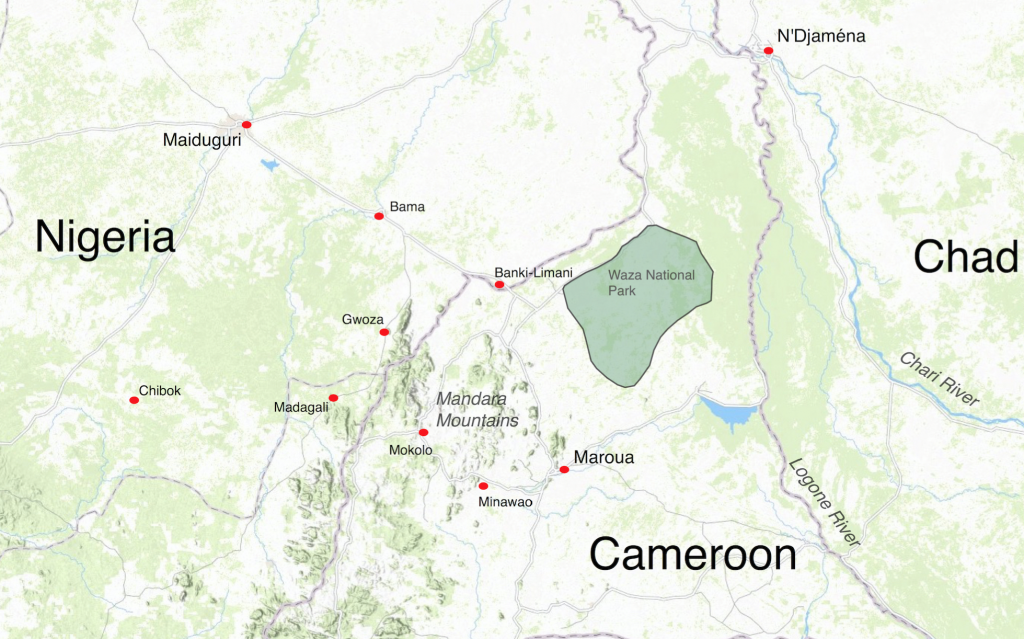

“Since beginning my PhD in northern Cameroon in the mid-1980s, I’ve spent a lot of time on both sides of Nigeria’s northeastern border with Cameroon,” MacEachern says. Much of his academic research has centered on the study of state formation and ethnicity in Iron Age Central Africa, but as he pursued this, MacEachern came up against a more current challenge: the emergence of Boko Haram.

“The area I’ve worked in from 1984 to 2012 is now subject to repeated Boko Haram attacks.” For a time, MacEachern was based in the Nigerian town of Gwoza, which later became the terror group’s headquarters until the Nigerian Army retook it in 2015.

“I was due to return to the area in 2014, but it was just too risky so we ended up doing excavations at sites one hundred and twenty miles to the south in Cameroon.”

Border issues

The presence of the international border between Nigeria and Cameroon is a key factor in the rise of Boko Haram, says MacEachern. “The border was drawn up in the early 1900s by the European colonial powers with scant regard for the communities it affected. Part of the border even bisected the main street of one of the old state capitals.”

As is often the case with international borders, it became a magnet for criminal activity. “Over the years I worked there, I would often run into smugglers and bandits. Many of the young men who today are Boko Haram operatives, fifteen to twenty years ago would have been running illegal gasoline across the border on motorcycles.”

While the group’s leaders tend to come from well-off, urban backgrounds, explains MacEachern, many Boko Haram foot soldiers are from a long line of economically and socially marginalized males with little or no prospect of improving their lives without going outside the law.

“In this part of the world, you are not regarded as a real man until you have a wife and a family, and for this you need a job and money for a dowry—something which is outside the grasp of many young men here, which makes them perfect recruitment fodder for criminal gangs or radical terror groups.”

When Boko Haram came to prominence in 2009 as an organization committed to the violent promotion of an Islamic state in Nigeria, it found a ready-made network of willing converts to the cause whose desperation could be exploited.

“The radicalization is real of course, but many Boko Haram operatives have not changed their activities much since being recruited: they were smugglers and bandits before and they are still smugglers and bandits,” says MacEachern.

Area affected by Boko Haram attacks

Mass kidnappings and slavery

One Boko Haram activity that is a new departure, however, is mass kidnapping. The most famous example is that of the 276 schoolgirls taken in 2014 from a secondary school in the northeastern Nigerian town of Chibok, which is only about thirty miles from where MacEachern had been working. He sees close connections between such kidnappings and pre-colonial slave-raiding.

“Some of those girls escaped, some have been released while others have been found or rescued, but there are still thought to be about a hundred of them missing, many of whom have likely been forced into servitude, sexual and otherwise.”

Boko Haram’s fondness for kidnapping and enslaving young women is a throwback to times when the Mandara Mountains, where MacEachern often works, were often used as a refuge against slave raiders from the north, going back 500 or 600 years. “The population I lived and worked among were people who saw themselves historically as refugees. Today, they see Boko Haram as simply more recent versions of those slave raiders.”

Slave-raiding had been mostly stamped out by the 1930s, says MacEachern, but has now re-appeared, thanks to the actions of Boko Haram.

Historical perspective

MacEachern brings his anthropological expertise to the story of Boko Haram, an approach he says sets his book apart from most existing literature on the subject. “The book stresses how Boko Haram is really a local group with deep historical roots in the region, rather than a straightforward, off-the-shelf, Al Qaeda ‘franchise,’ which is how it’s often described.

“The first few chapters contain a lot of archaeology. I argue that the artifacts we had been digging up for all those years—which tell us a lot about the political structures and the slave-based economy that existed hundreds of years ago—also reflect the deep origins of Boko Haram today.”

Current threat?

Currently, Boko Haram is on the defensive militarily, and that, says MacEachern, is because the Nigerian authorities now take this battle very seriously and commit a lot of resources to it.

“Following the Chibok kidnappings, Nigeria struck a military agreement with its geographically huge northeastern neighbor Chad, which has some of the best-trained armed forces in the region.”

The government in Abuja, explains MacEachern, also now employs a number of aging, white mercenaries from South Africa, veterans of the apartheid-era border wars and experts in counter-insurgency warfare.

“These guys, many of whom are now in their sixties, have a brutal background, but they’ve proved effective in directing operations against Boko Haram, and have helped break up a lot of the territory controlled by the terrorists.”

However, there are still kidnappings and suicide bombings, and Nigeria is ranked by Western governments as a very high-risk destination. MacEachern has many friends and contacts in the border region where he worked for so many years. and he maintains regular contact with them through social media. He plans to continue fieldwork further south in Cameroon, but as for returning to the area affected by Boko Haram to continue his excavations, that option remains firmly off the table, at least for the time being.

Scott MacEachern will be discussing his new book, Searching for Boko Haram: A History of Violence in Central Africa, on March 1, 2018, in the Nixon Lounge of the Hawthorne Longfellow Library, at 4.30 pm. The event is free and open to the public.