Works on Paper of the Month at the Bowdoin College Museum of Art

By Bowdoin College Museum of Art

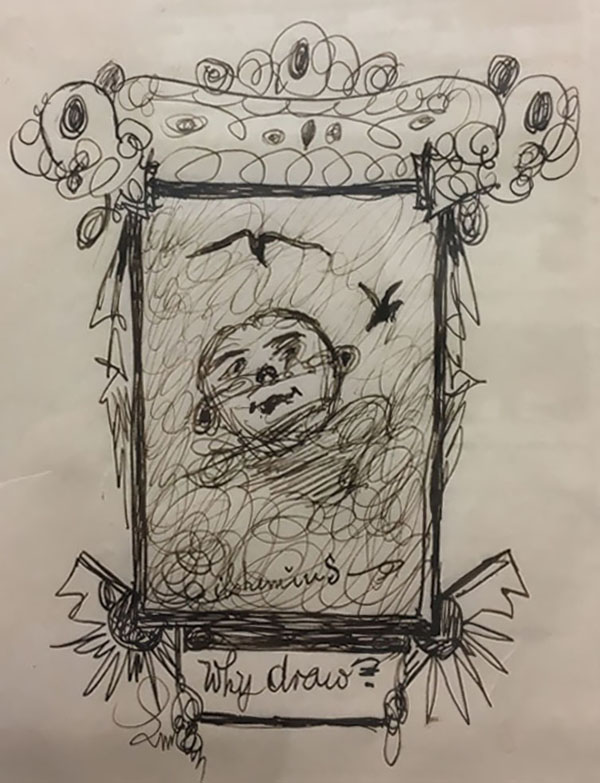

Louis Eilshemius (American, 1864–1941)

Four pen and ink drawings on stationary, ca. 1932–1938

Why Draw?

Smoke

A Roulade of Lines

At the Back Bat (?)

This group of four drawings, recently purchased at auction, is characteristic of Louis Eilshemius’s late work. Disgruntled with the art world, which, he believed, unfairly ignored him, and ailing from a traffic accident in 1932, Eilshemius stopped painting and focused his energy on inflammatory letters to the editors of major news outlets. He routinely signed his missives with self-aggrandizing titles such as “Mightiest Mind of Mankind,” “Minister of Art to Be,” or “Neglected Potentate.” The stationary he used to voice protest also served him to record spontaneous doodles. These drawings suggest figures and landscapes, often bordering abstraction, with richly ornamented frames. The drawings are usually inscribed with self-referential, often hilarious titles. They are among the most unfiltered expressions of Eilshemius’s satirical humor, love and understanding of art, and free-wheeling imagination.

Painter, poet, and publicist Louis Eilshemius (born in North Arlington, New Jersey, 1864, died in New York, 1941) went to school in Switzerland and Germany before enrolling briefly at Cornell University. He studied painting at the Art Students League in New York and the Académie Julian in Paris. Independently wealthy, he traveled to Europe, North Africa, the South Pacific, New Zealand, California, and Rome. Under the influence of the Barbizon School and emulations of Albert Pinkham Ryder’s work, he created a distinct and personal style related to late Symbolism. While he felt underrated for most of his life, he had a following. Several influential members of the first generation of collectors of modern art, such as Duncan Phillips and Joseph Hirshhorn, admired the eccentric artist and bought large quantities of his work. Artists from Louise Nevelson to Jeff Koons were and are devotees and collectors as well. A spate of recent exhibitions and publications might finally succeed in drawing the attention of a wider public to Eilshemius’s work.

To aficionados it provides a rewarding case study for the complexities of art history of the first decades of the twentieth century. Undeterred from artistic trends, Eilshemius combined the subject matter provided by academic tradition and especially orientalism—landscapes, nudes, allegories, and portraits—with an idiosyncratic, deeply personal style. His passion was antagonistic to current European innovations. Instead of aligning himself with the avant-garde, Eilshemius filled sometimes clichéd subjects of the past with life and urgency. These tired tropes obviously mattered to the artist in a way that seemed unwarranted to most Modernists at the time.However, in 1917 Marcel Duchamp, the French-American Dada artist and agent provocateur, declared that Eilshemius was one of his favorite American artists. Duchamp had thought more deeply about artistic innovation than most of his contemporaries. He understood that artistic expression, in order to communicate authenticity, required specific strategic moves and formal innovations. Eilshemius’s work refused to play by the rules of this game and thus unsettled—and made visible—basic assumptions about the tenets of avant-garde art. The recent monumental study by Stefan Banz on the work of Louis Eilshemius for the first time asserts that Duchamp’s admiration for Eilshemius was, in fact, real, and not ironic. His valid argument invites a reappraisal of the work not only of Eilshemius, but also of Marcel Duchamp. A possible starting point for such a reevaluation are Eilshemius’s late drawings, whose irreverent humor still seems edgy today.

Joachim Homann

Curator