Whispering Pines: One Hearth, Many Lives

By John Cross '76 Bowdoin’s oldest building—Massachusetts Hall—turned 215 this year. No other building on campus has served more functions or undergone a greater number of modifications over the years.

Bowdoin’s oldest building—Massachusetts Hall—turned 215 this year. No other building on campus has served more functions or undergone a greater number of modifications over the years.

In the 1780s residents of the District of Maine (then a part of Massachusetts) began petitioning the General Court of Massachusetts for an institution of learning. Despite lobbying by prominent citizens in Portland, Freeport, and Winthrop, Brunswick was chosen as the location for Bowdoin College. The College’s charter was signed by Massachusetts Governor Samuel Adams in 1794, with income to support the fledgling college coming from the sale of public land in five townships in central Maine and the sale of 1,000 acres given by James Bowdoin III in the Town of Bowdoin.

It took two years for the Trustees and the Overseers to agree on a location for the College within Brunswick, and another two years (1798) before the sale of land had generated sufficient income to begin construction of a single brick building near intersection of three roads (to Harpswell, to New Meadows, and the “12-rod road” that ran from the falls of the Androscoggin River to Maquoit Bay). The original plan was for a three-story brick building similar to Hollis Hall at Harvard, although the final version was scaled down. The Governing Boards entrusted the project to Overseer of the College John Dunlap and engaged local housewrights Samuel Melcher III and Aaron Melcher to do work. Bricks made in Portland were offloaded at New Meadows and were brought by wagon across the blueberry plains of East Brunswick. According to the account book of Trustee Charles Coffin, workers were paid in West Indian rum for their labor. One expense item was a pound of gunpowder to set off an explosion to celebrate the completion of the roof.

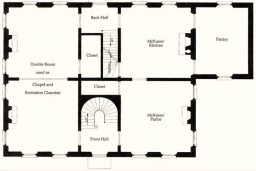

The slower-than-anticipated sales of land granted to the new college by the Commonwealth of Massachusetts brought construction to a halt, however, and the building was boarded up for nearly two years, providing shelter for bats, transients, and opportunists who stole lead from the flashing around the chimneys. Despite these minor setbacks, work resumed in 1801 and Bowdoin College opened in September of 1802. Until President McKeen’s house was completed in 1803, Massachusetts Hall contained the entire College—President McKeen and his family, the eight students of the Class of 1806, a kitchen and pantry, and a recital chamber/chapel. A first-floor plan appears in Charles Calhoun’s A Small College in Maine, based on the recollections of Professor Alpheus Spring Packard of the Class of 1816.

With the admission of subsequent classes, it was apparent that additional space was needed. An unheated wooden chapel was built in 1805 and Maine Hall was completed in 1808 (a better approximation of Harvard’s Hollis Hall than Massachusetts Hall had been). As the campus began to grow, a bell and cupola were added to Massachusetts Hall so that students could be summoned to prayers at dawn and dusk. According to historical research by Bowdoin junior (and later Bowdoin President) Roger Howell Jr. ’58, the cupola was removed from Massachusetts Hall in 1830 and much-needed roof repairs were completed. Professor Parker Cleaveland’s mineral and natural history collections and his chemistry classroom expanded within the confines of Massachusetts Hall, and they briefly shared space with the College’s library and art collections before these were moved to the second floor of the old chapel.

When Maine became a state in 1820, the Medical School of Maine was established at Bowdoin, where it occupied the top floor of Massachusetts Hall for the next forty-one years. Professor Cleaveland felt that the space in Massachusetts Hall was adequate for needs of the undergraduate science and medical school curricula. After his death in 1858, his successor, Paul Chadbourne, sought to expand instruction in the sciences, which eventually led to the construction of Adams Hall in 1861.

After the Medical School moved to new quarters, the sixty-year-old Massachusetts Hall was showing signs of wear, and College officials considered tearing it down in favor of a new building. Peleg Chandler of the Class of 1834, Professor Cleaveland’s son-in-law, offered to remodel Massachusetts Hall at his own expense to create a first-floor recitation room and to house the Cleaveland Cabinet of mineral and natural history specimens. The Governing Boards accepted his offer in 1872, and architect A.C. Martin of Boston was selected for the project. The original central staircase was removed; twelve of the original thirteen fireplaces were closed up; a neo-Classical entrance with Doric columns was created on the east end of the building; a second story was added to the east side ell to accommodate a stairway that led to the second floor; and the second and third floors were combined into a single museum room with an upper gallery for display cases, reached by spiral staircases.

There were specific conditions in Chandler’s deed of gift—that the first-floor lecture/recitation room be used exclusively for that purpose, that the College maintain the Cleaveland Cabinet in the building; and that no changes were allowed without the permission of Peleg Chandler and his children during their lifetimes. After the completion of Searles Science Building in 1894, however, many of the biological collections were moved out of the Cleaveland Cabinet. When the Visiting Committee’s report for 1911 described the conversion of the first-floor recitation room into administrative space and mentioned the use of the Cabinet for faculty meetings, it triggered a response from Horace C. Chandler of Boston, the last surviving child of Peleg and Mary Cleaveland Chandler. Chandler often visited the family home on Federal Street, and he checked out the situation in Massachusetts Hall. He found the College’s stewardship of the Cleaveland Cabinet to be less than satisfactory and in violation of the spirit and the letter of the original agreement.

It took several years of correspondence among Chandler, President William DeWitt Hyde, the Trustee Committee on Finance, and the Faculty Committee on Grounds and Buildings to work out a negotiated settlement. The College agreed to restore the appearance of the Cabinet, including hanging portraits of Cleaveland and Peleg Chandler, and displaying Longfellow’s autographed sonnet about Cleaveland. The Cleaveland herbarium and geological collections were returned to Massachusetts Hall from Searles, and that faculty meetings could be held in the central area of the museum, provided that chairs of an appropriate (colonial) style were purchased by the College (they were—four dozen Windsor chairs, at $72 a dozen, from the Paine Furniture Company in Boston). By the Commencement of 1915 all was in order. The new agreement was guaranteed for the lifetimes of Horace Chandler and his children.

By the 1930s, however, the College needed additional administrative space, and they sought (and obtained) the permission of the Chandler heirs to return the internal arrangement of Massachusetts Hall to a version of its pre-1873 configuration. Architect Felix A. Burton (Class of 1907) had a gift for understated elegance and period detail; few today recognize the magnitude of the transformation that was required. The front staircase was reconstructed. The east portico was removed, and a new entrance to the President’s office was created on the north side of the ell. If you look carefully, you can see the outlines of the columns from the portico in the brickwork of the east side of the building. The second and third floors were re-established and partitioned into rooms, with a new faculty room taking up much of the third floor. The roof was raised. The stone Cleaveland Cabinet tablet was moved to the front entrance hall, opposite the plaque from the 1936-40 renovation, while a bronze plaque honoring the Rev. Elijah Kellogg of the Class of 1840 that had been affixed to the outside west wall was relocated to the vestibule of the Chapel. Burton’s restoration left three functioning fireplaces out the original thirteen.

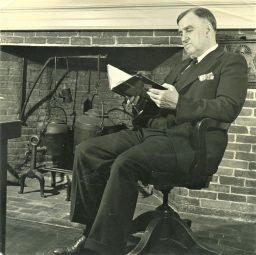

Until Hawthorne-Longfellow Library was completed in 1965, Massachusetts Hall remained the administrative hub of the campus. Within its cozy confines one could find the president, the dean, the secretary of the College, the treasurer, the bursar/payroll office, admissions, the alumni office, and the placement office. The migration to Hawthorne-Longfellow by administrative offices opened Massachusetts Hall for faculty and classroom use. As the faculty has increased in number, the philosophy and religion departments have since relocated, leaving the English department as the sole occupants of Bowdoin’s oldest—and most significantly modified—real estate. Despite all the structural changes to Massachusetts Hall over the years, something abides from the College’s first days. Students listening to a lecture in the third-floor classroom are connected to the recitation rooms and living spaces of the students from the Class of 1806, and those who meet for a seminar in the old McKeen kitchen on the first floor can see in the fireplace the iron pots that were among the scientific equipment given to Professor Parker Cleaveland by English chemist Sir Humphrey Davy. In Massachusetts Hall we have, in a figurative sense, the hearth from which the ever-evolving experiment that is Bowdoin College began.

With best wishes.

John R. Cross ’76

Secretary of Development and College Relations