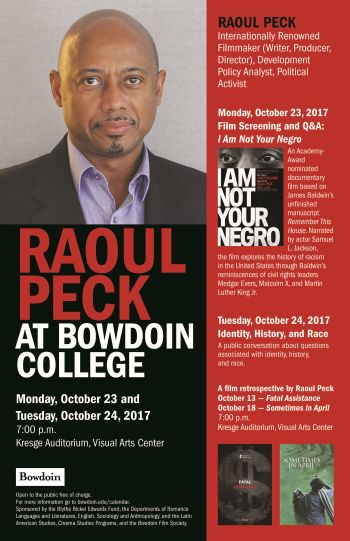

‘I am Not Your Negro’ Filmmaker Raoul Peck Visits Bowdoin

By Carly Berlin '18

On Monday evening, Oct. 23, students and faculty filled Kresge auditorium for a screening of Peck’s Academy Award-nominated film, which is based on writer James Baldwin’s unpublished manuscript, Remember This House.

The following night, on Tuesday, many returned for a discussion with Peck, moderated by Assistant Professor of Romance Languages and Literatures Meryem Belkaïd.

Preceding the film screening, Associate Professor of English Guy Mark Foster provided the audience with a brief introduction to Baldwin. “The world was not designed around affirming Baldwin’s identity as a boy of African descent,” said Foster, who taught a senior seminar on Baldwin last spring. “That world was hell-bent on destroying any possibility that such a boy would grow into adulthood possessed of any idea, of any identity that was not preconceived by the white majority.”

Baldwin’s writing, Foster said, explains many aspects of our current condition. Rather than argue this himself, Foster read a passage from Baldwin’s extended essay, The Fire Next Time (1963), written as advice to the author’s teenage nephew: “Take no one’s word for anything, including mine. But trust your experience. Know whence you came. If you know whence you came, there is really no limit to where you can go. The details and symbols of your life have been deliberately constructed to make you believe what white people say about you. Please try to remember that what they believe, as well as what they do, and cause you to endure, does not testify to your inferiority, but to their inhumanity and fear.”

In the film I am Not Your Negro, Peck, too, privileges Baldwin’s word. By grounding the author’s reflections on his relationships with — and the murders of — his peers, Medgar Evers, Malcolm X, and Martin Luther King, Jr., Peck tells a larger story of American racism. The story does not end with the civil rights movement; rather, it provokes us to recognize contemporary racism. Familiar film footage from the ’50s and ’60s is colorized, while images from Black Lives Matter protests are shown in black and white, forcing the audience to confront the relevancy of the past, and its foundation for current American unrest. Peck’s film is an homage to an author — but it is also a revision.

Peck received a standing ovation as he entered Kresge auditorium upon the film’s conclusion. In a brief discussion with Foster, Peck talked of his process in creating the documentary.

It took at least ten years. Peck spent the first three or four just searching Baldwin’s complete archives for an entry point to the film. Yet in truth, he pointed out, the work was a lifetime in the making. He was just seventeen or eighteen when he first discovered Baldwin’s books. “They changed my life, my way of seeing the world around me, the way to structure my thoughts,” he said. “They showed me how to not let anybody define me, who I was, my future. At that time, it was rare to have any writer, or scholar, where you could feel totally at home.”

For Baldwin, Peck continued, “race is just the starting point of his discourse.” Above all, the author teaches “how we treat people that are different to us.”

The humanism at the core of Baldwin’s writing pervades much of Peck’s other projects and life experiences. On Tuesday evening, students and faculty reconvened for a discussion with Peck that focused more on his career trajectory and greater filmography. Peck talked of his upbringing in Haiti and his family’s relocation to the Democratic Republic of Congo to flee the Duvalier dictatorship, when Peck was eight. These two countries are the subjects to several of Peck’s earlier films, including Fatal Assistance (2014), on responses to Haiti’s 2010 earthquake, and Lamumba (2000), about the Congo’s achievement of independence from Belgium in 1960.

Peck’s education and career path also propelled him around the globe. He traveled to France and then Germany to study industrial engineering, to New York to work as a taxi driver, photographer and journalist, back to Berlin to earn a film degree, and later he returned to Haiti to serve as minister of culture in the Haitian government in 1996. He resigned from this position a year later in protest of Presidents Prevál and Aristide.

Speaking at Bowdoin, Peck concluded, “People don’t become the way they are just by magic. There is always a story of the human being behind it. Mankind makes history. And if man makes history, man can change history.”

Peck’s visit to Bowdoin was sponsored by the Blythe Bickel Edwards Fund, the Departments of Romance Languages and Literatures, English, Sociology and Anthropology, and the Latin American Studies, the Cinema Studies Programs, and the Bowdoin Film Society.