'Bound and Determined': Special Collections Curates Book Exhibition with a Twist

By Tom Porter

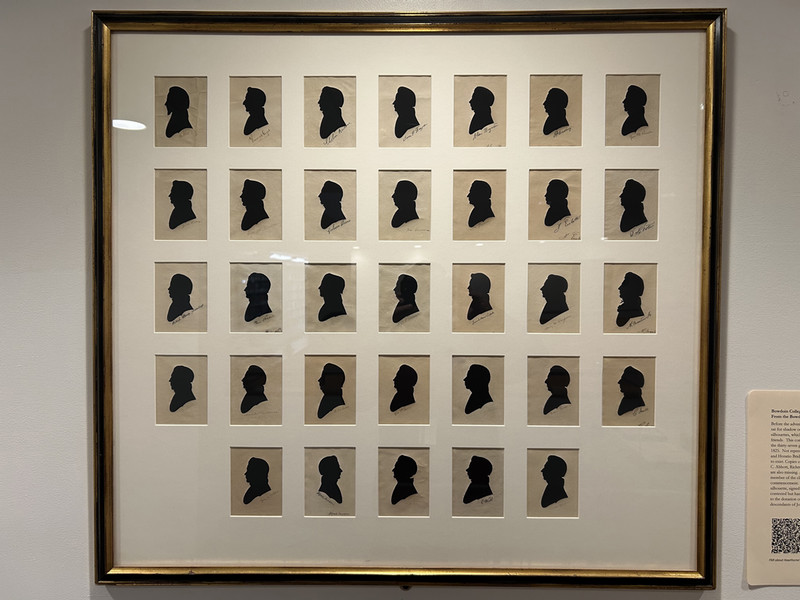

An exhibition on the second floor of the Hawthorne-Longfellow library highlights Bowdoin’s collection of rare books. But, unusually perhaps for a show about books, this exhibition is wholly unconcerned with the contents of said books.

“We approached this exhibit in a totally different way,” said Marieke Van Der Steenhoven, education and outreach librarian at the George J. Mitchell Department of Special Collections and Archives, which is responsible for the exhibition. “We look at the physical aspects of the book—the binding, the paper, the illustrations, the print—not at what the book is about or what it says. Hence the line we use on the show poster, ‘Books tell stories beyond their words.'”

“Bound and Determined: The Remarkable Physical History of the Book” runs until January 15, 2018. Van Der Steenhoven, along with Special Collections Director Kat Stefko, curated the show, which also features a number of talks by faculty and visiting lecturers. On Friday, October 13, Peter M. Small Associate Professor of Art History Stephen Perkinson will lead a conversation about the early printed book.

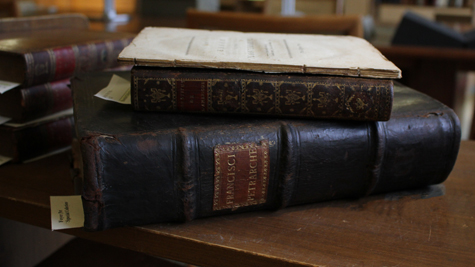

“The oldest printed book we have on display is from 1487,” said Stefko. “It’s a Bible, but we’re more interested in what the book physically demonstrates, which is the transition between print and manuscript form.” Early printing was an expensive and complex process, she explained, and often printers relied on both old and new technologies to achieve their purpose. “Early printers commonly printed the main text but left gaps on the page for scribes to fill in with enlarged or ornate initials. Adding such details, often in red ink, was simply faster and cheaper to do by hand.”

As well as keeping the costs down, said Stefko, this approach also made these early printed books more acceptable to the audiences of the day. “There were certain expectations about what a book should look like, which included these oversized, decorated initials. It was part of the aesthetic and printers tried to mimic that as best they could.”

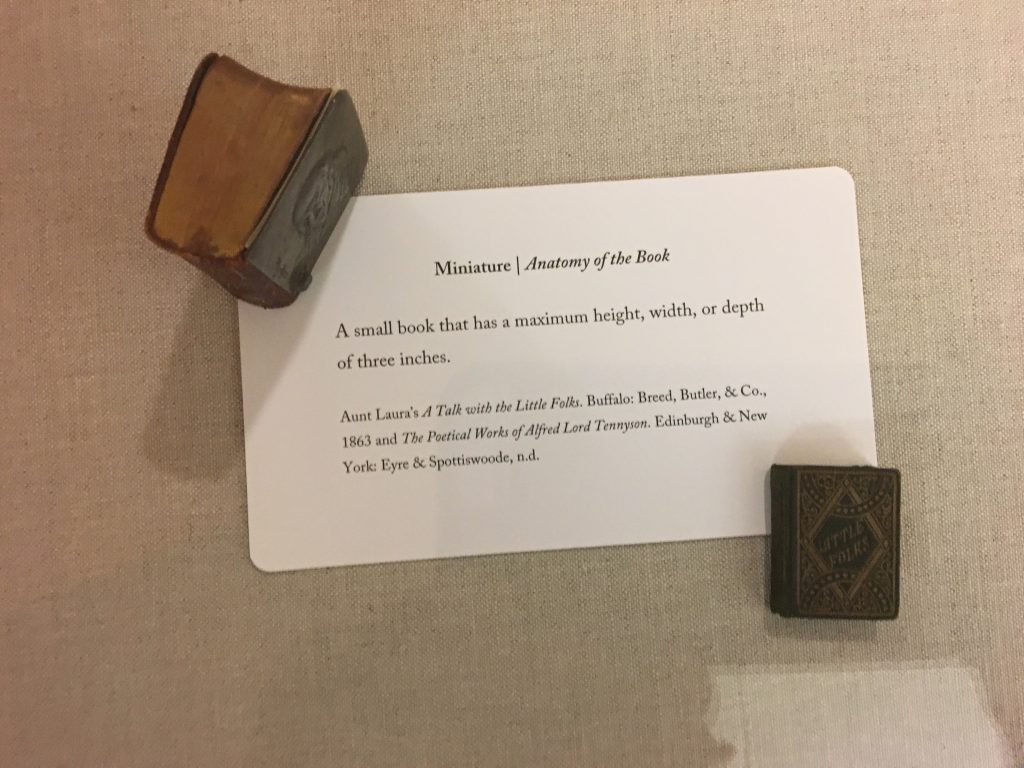

There is an early e-reader on display as part of the exhibition, in a section dealing with non-codex books, or books that are not bound at the spine but demonstrate alternative definitions of the ‘page’ and the act of reading. This includes a scroll from Yemen dating back to the seventeenth century containing part of the Hebrew Bible, and a palm leaf book that looks like a fan and is thought to originate from nineteenth century Myanmar.

Some of the earliest known writing on the planet can be found on cuneiform tablets, created by the Sumerians some five thousand years ago in what today is Iraq. While there is no original tablet on display here, there is a replica, explained Van Der Steenhoven. “It was printed using the 3D printer at Hatch Science Library, which is really exciting. Our colleagues at Cornell scanned tablets from their collection and shared the 3D pattern for public use.”

Not that Bowdoin is without its own examples of original cuneiform text. They can be found on several Assyrian relief sculptures—thought to date back nearly three thousand years—on display at the Bowdoin College Museum of Art, a few yards away from the library. “Transporting them to the library for this exhibition was an impractical idea,” said Stefko, “but we did collaborate with the museum in the opening of the show, which featured a lecture by renowned bibliophile Nicholas Basbanes about the history of paper and the book.”

When it comes to defining exactly what a book is, Van Der Steenhoven is reluctant to answer that question definitively. “I think the conversation around that question is what helps us think about books and their value,” she said. “For example, book artists have helped us expand our understanding of what a book is, or can be. Can a mussel shell be a book when we open it up? Do books need to be made from certain materials? In ancient Peru for example, the Incas recorded information on ropes. Is that a book?”

Van Der Steenhoven and Stefko frequently work with academic departments helping faculty utilize the resources available in Special Collections in their teaching. “One of the great things about this exhibit,” said Stefko, “is that it has given us a chance to re-familiarize ourselves with the collection in a new and interesting way, and that, in turn, helps us articulate to faculty and students the teaching and learning potential of books as objects.”