A Race to Save the Artifacts

By Bowdoin News

Archaeologist LeMoine in her office at the Peary-MacMillan Arctic Museum.

Photograph by Fred J. Field.

LeMoine is a quietly spoken but determined Canadian archaeologist with a passion for the Arctic. Curator at Bowdoin College’s Peary-MacMillan Arctic Museum, she was in Greenland trying to unravel a thousand-year-old anthropological conundrum, but on arrival, her concerns have more to do with the here-and-now. A global problem was staring her in the face.

As she surveyed the dig site — a remote former Inuit settlement called Iita — she encountered a world she barely recognized: retreating sea ice, along with the recession of a crucial layer of protective permafrost, signaled a pressing archaeological problem that threatens the past, present, and future. Time was running out.

A Familiar Region

The Arctic is familiar ground to LeMoine. She’s visited the region many times in the last thirty years. Her path to being an Arctic explorer began while she was in high school in Ontario, Canada. A government-sponsored program to recruit student workers, including archaeologists, provided an opportunity to combine her love of history and her desire to be outdoors.

LeMoine went on to major in anthropology at the University of Toronto, where her interest in bone tools came alive during digs for Native American relics in North America.

“I was with a seasoned group of people and that first trip was so wonderful that I've never looked back.”

—Genny LeMoine

While working toward her doctorate at the University of Calgary in 1986, she was invited on her first Arctic field trip. As she packed her bags, she admits she felt a little trepidation, for this would be an entirely new experience not to mention a new level of cold, even by Canadian standards.

“I was a little nervous as we flew into this very remote camp,” LeMoine recalls. “But I was with a seasoned group of people, and that first trip was so wonderful that I’ve never looked back.” She even discovered a benefit to her new frigid surroundings.

“I found that in the high Arctic, artifacts were incredibly well-preserved due to the extreme cold.” But that is starting to change, as LeMoine realized last year.

Journey to Iita

The 2016 expedition begins with quite a journey. Four days of travel, including two military transport flights and a helicopter ride, were made longer than usual when LeMoine and her five colleagues encountered a hazard of the job, when such work takes you inside the Arctic Circle.

They were snowed in for two days—in the middle of June—at the Thule Air Base, in northwest Greenland. When the storm cleared and the runway was dug out, they finally made it to their own dig site.

Iita, once the most northerly populated settlement in the world, is located in a fjord — a long, narrow inlet of sea between high cliffs, formed by glacial erosion.

It’s more than a thousand miles north of Nuuk, Greenland’s capital, and less than 800 miles from the North Pole. Though thoroughly remote, it attracts hunters in the summer, enticed by the abundance of polar bear, musk ox, and walrus—and researchers like LeMoine.

The area has had its share of western explorers and scientists over the years, including Arctic explorers and Bowdoin graduates Robert Peary and Donald MacMillan.

The remains of the building erected by MacMillan’s team as they embarked on the ill-fated Crocker Land expedition (1913-1917) are still visible on the surface near the site where LeMoine and her colleagues would dig.

Three packed-full helicopters brought LeMoine and five teammates—Lara Bluhm, a member of the Bowdoin College Class of 2017; Hans Lange, curator at the Greenland National Museum and Archives; Nuka Larsen, a University of Greenland student; John Darwent, a research associate at the University of California, Davis; and UC Davis PhD candidate Jason Miszaniec—to Iita with the supplies they would need to work and survive for six weeks.

“It may sound like a lot for just six people, but each person needs up to 3,000 calories of food per day—and we need to have an extra ten days of rations, in case the weather closes in and cuts us off.”

Meet the Crew

A Race to Save the Artifacts - Why it Matters

A Quest Against Time

LeMoine’s return to Greenland and to Iita was part of an ongoing quest to discover more about the people who lived there—a quest now imbued with a deep sense of urgency due to the changing climate.

“The sea ice had retreated to such an extent that we had to access the dig site by walking across dry land, which is rocky and difficult underfoot,” she said. “Previously, in 2006 at the same time of year, we simply walked much of the way from our campsite along the so-called ice foot—the fringe of ice still frozen to the land—which was much easier.”

This revelation was a critical moment for LeMoine. With warmer summers causing the ground to soften and erode, and a crucial layer of protective permafrost to recede, LeMoine could see that time was running out. Artifacts still in the ground would begin disintegrating at a much faster rate.

“As archaeologists, we can’t do anything to stop the rising seas and the retreating sea ice, but we can work together to try to capture what we can before it goes.”

She says this attitude represents a new trend in archaeology and cultural heritage management.

A Thousand-Year-Old Question

It’s hoped that learning more about who lived at Iita can help solve the other challenge that has brought LeMoine and her team near the top of the earth: the thousand-year-old question of whether two cultures who inhabited northwestern Greenland—the Thule and the Dorset—ever coexisted. With funding from the National Science Foundation, LeMoine is looking to uncover how these different groups used the natural resources available to them.

“There is no evidence today of Dorset DNA anywhere. They are truly a dead people.”

The Dorset people were the last of the earliest known occupiers of this part of the world, inhabiting the region 1,800 to 800 years ago before dying out.

“There is no evidence today of Dorset DNA anywhere. They are truly a dead people,” LeMoine says. The Thule (pronounced “Too’-lee”) arrived about 800 years ago and are the ancestors of the modern Inuit. The two peoples had distinct cultures, and consequently the tools they used were noticeably different.

“The tools are quite easy to tell apart if you know what to look for,” said LeMoine. “The harpoon heads are different shapes. Dorset used flaked stone tools, while Thule used more ground stone tools.” Both groups took advantage of the unusual presence of iron due to a large meteorite that had happened to fall in the area.

The Artifacts: What they Might Tell Us

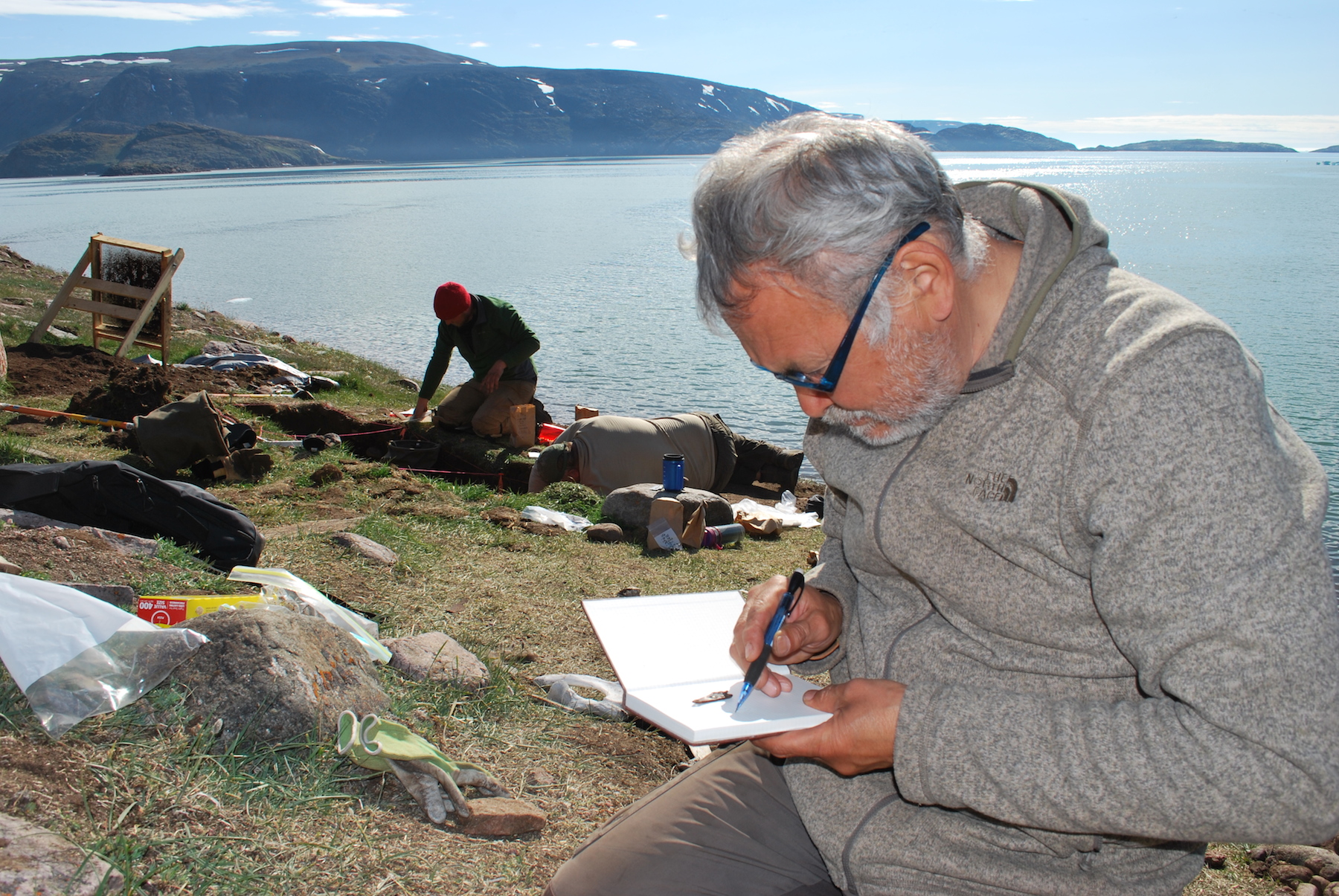

Working near the water’s edge with triangular trowels in hand, LeMoine and the others dig through wet soil in hopes of finding clues to Iita’s history before it’s too late.

“Often what you’re looking for are stone tools or things like that, and the dirt’s full of little pebbles, so you’re always hearing that sound, of the trowel hitting stone, but eventually you learn the distinctive sound of the particular stone that they make tools out of,” says LeMoine, who says the excitement of such a find can’t interfere with the careful process required with such work.

“When you start uncovering an object your first reaction is you want to see what it is very quickly, but you know you have to be very careful because you don’t want to scratch or break it.”

Timeline: A mystery that started a thousand years ago is being studied still today—but the answer might be washing away.

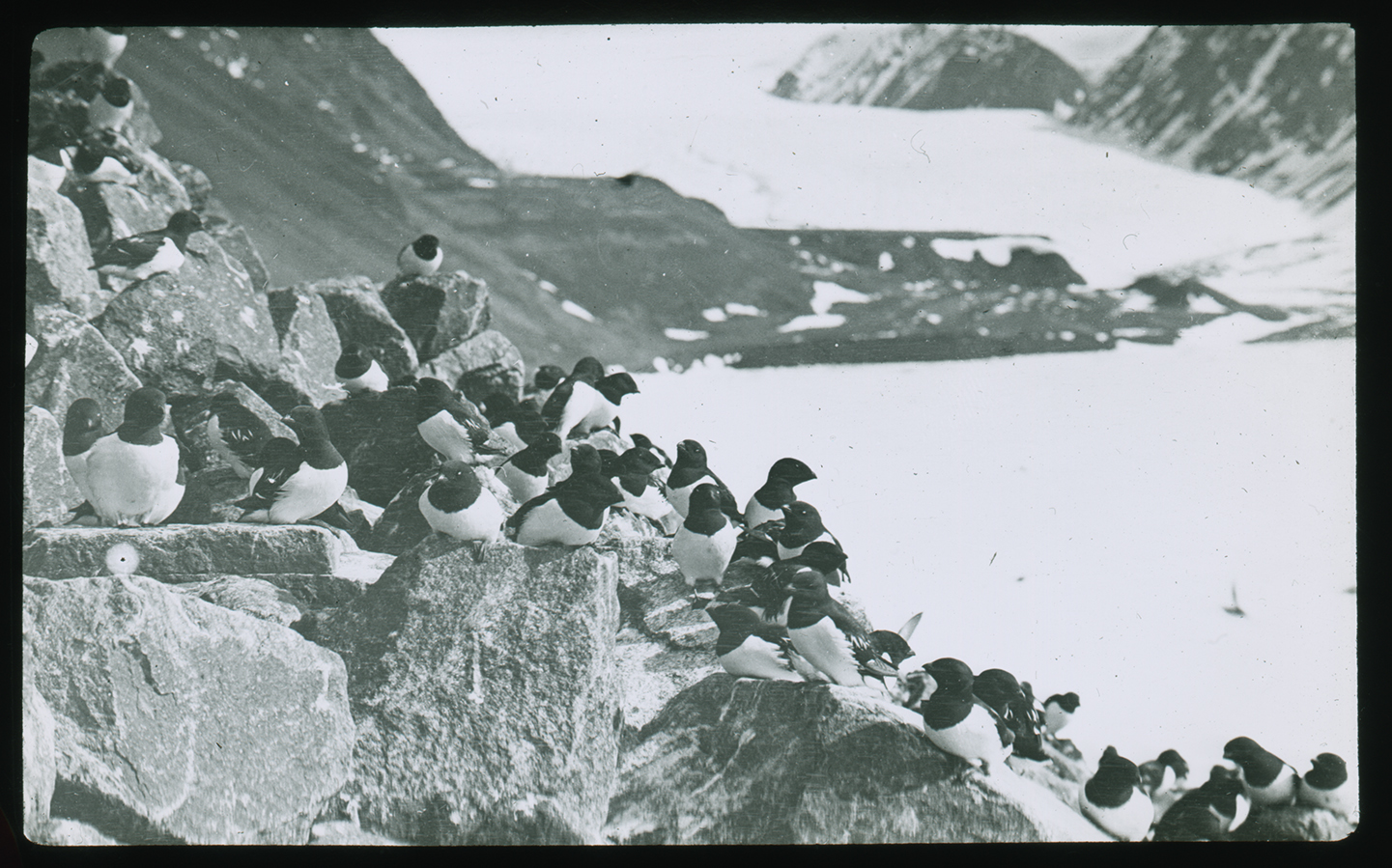

Thousands of bones from sea birds known as auks were excavated and an important resource environmentally and culturally for the Dorset people, as well as the later Thule.

Image credit: Little Auks on talus slope, unidentified photographer, Foulke Fjord, Northwest Greenland, 1913-1917. Silver gelatin on glass. Given in honor of Walter E. Ekblaw, Jr., devoted son.

They uncover Thule tools and Dorset tools. It is clear to these trained experts to which culture each belongs, but existing evidence shows one culture influencing the other. Harpoon heads found during previous digs in known Thule settlements seem to show the influence of later Dorset culture. Whether the Thule learned from the Dorset directly or simply copied Dorset tools found in the ground is unknown. They also find seemingly whimsical carvings of polar bears, a swan, and human figures, including what appears to be a man waving.

John Darwent, the research associate from UC Davis, made one of the most dramatic discoveries of the 2016 trip. He found a surface containing artifacts of both the Thule and the Dorset people, suggesting they may have overlapped. “If they didn’t overlap,” said LeMoine, “they at least appear to have occupied the same ground.”

They also excavated thousands of bones from sea birds known as auks, nearly half a million of which nest in the fjord at Iita every summer. “This avian colony is an important resource,” said LeMoine, “environmentally and culturally, and was used by the Dorset people, as well as the later Thule.”

During their six weeks at Iita, LeMoine and team collect between 400 and 500 artifacts. They’re being cataloged and stored at UC Davis before being sent to a lab for radiocarbon dating. “Carbon dating will play a crucial role in establishing a timeline,” LeMoine said, but concedes it may not be able to provide conclusive proof that the Thule and the Dorset lived side-by-side.

That work falls to LeMoine and her fellow archaeologists, and to anthropologists. She says though we may never know whether the two peoples ever came face-to-face, researchers hope to learn more about how these earlier cultures survived in this environment, or in the case of the Dorsets, why they died out, which remains a mystery.

“They had survived for thousands of years, so what was so different about this era?” LeMoine asks. “There’s no evidence that they were wiped out in a war. It could have been disease or environmental factors, we just don’t know.”

We also do not know what size the Dorset population would have been in their later years, when they may or may not have overlapped with the Thule.

“We could be talking quite small numbers,” said LeMoine. “The minimum size for a sustainable community in the Arctic is about 250, so they could have dwindled to that size by the end, and Iita may have been one of the last places they lived.”

John Darwent, research associate at the University of California, Davis, talks about some of the artifacts found during the six-week expedition at Iita in Greenland.

Iita's Geography

A number of factors make Iita a fascinating geographical site, explains LeMoine, who says first and foremost that it must be regarded in the context of a process called “post-glacial rebound,” which is most evident in the Arctic where ice from the Pleistocene, or Ice Age, melted most recently.

“Since the last Ice Age ended less than 12,000 years ago, the glaciers have been steadily diminishing in size and weight, which is causing the land to rise, or rebound,” LeMoine said. “It’s technically still climate change, it’s just from a long, long time ago, so it’s not human-caused, or anthropogenic.”

As the land rises, successive generations of Arctic communities, which typically lived near the water, sited their settlements closer to the shore, leaving remnants of their forefathers literally behind them, further inland.

“Consequently, artifacts from older communities are found higher up and further inland,” explains LeMoine, “which is counter-intuitive when you think about it, as you would expect older relics to be deeper in the ground.”

But this is not your typical Arctic dig site. It’s on a steep gravel slope. It’s near a fast-running creek. It features more vegetation than is usual in this part of the world, to the point where LeMoine even describes it as “lush.”

Also remember that though the land may be rising in this part of the world and getting further away from the sea, modern climate change is having an impact of its own.

“So we have a combination of factors at Iita,” LeMoine says. “Sand and gravel are coming down from higher up, burying the occupation levels, while the site is also being destroyed by the relentless crashing of waves into the bank, which, with less sea ice, is exposed to them for longer each year.”

Why the topography at Iita has evolved as it has is unknown. “We need to get a trained geologist up there to take some samples and conduct an academic study,” said LeMoine. It remains one of the many unknowns about this part of the world.

A Changing Landscape

“I didn’t foresee the climate changing so dramatically back in the 1980s. Nobody did.”

There are scant historical records for vast areas of the Arctic—representing deep voids in our understanding that scientists like LeMoine spend their careers trying to fill, as they race against time and the effects of climate change.

“This ticking clock is partly what drives me on during those miserable moments on a dig, when you’re on your hands and knees, aching, it’s cold and rainy, and lunch is two hours away. That and the hope of discovering the next, old, new, big thing to show to the world,” says LeMoine.

Up Next: