Hugh Cipparone ’19: Optimism and Uncertainty about Aquaculture's Future

By Rosemary Armstrong

****************************

By Hugh Cipparone

Beyond the railing of the Chebeague Island ferry, I saw the rocky coastline of Maine. The ferry teemed with beachgoers, island residents and aquaculturalists. Beside me sat two leaders of Maine’s aquaculture community — Dana Morse, of Maine SeaGrant, and Ethel Wilkerson, of Manomet Center for Conservation Studies.

We soon arrived at the Chebeague Island pier. On a gorgeous July Sunday, cars filled the parking lot. I opted to walk the two miles to the Chebeague Island Boat Yard, the location of the first annual Chebeague Island Aquaculture Festival. As I walked, I imagined a festival on a flat, green field full of white tents. But when I arrived, I discovered the white tents sat behind the island’s post office, toward the back of a standard New England boat yard. The location felt more fitting than the verdant picture I had created in my mind. Connected to the water on which it relied, the Aquaculture Festival attached its events to real-life applications.

The first people I met at the Aquaculture Festival were a group of college-aged students. Originating from parts of the country as far away as Maryland and Chicago, these twenty-somethings had heard about the festival through their work at the Bigelow Laboratory for Ocean Sciences, in East Boothbay When asked about the future of aquaculture, they were unequivocal. “We need it,” said Eric Walton, a recent Colby graduate. As wild stocks decline in the face of a changing oceanic environment, only aquaculture can support local fisheries, he contended. When questioned about whether wild and farmed fisheries could coexist, Julia Park also answered positively, stating that these two potentially opposing forces could coexist if farmed fisheries were managed sustainably.

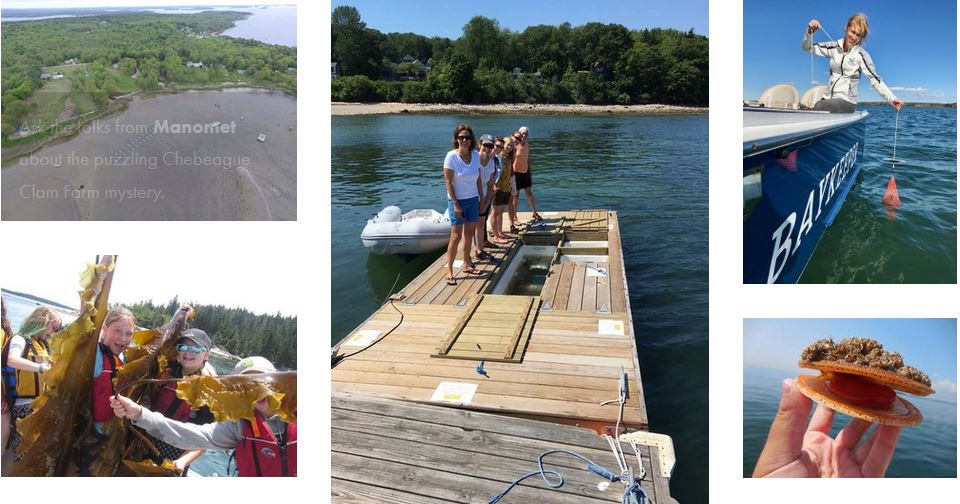

This optimism about the future of aquaculture continued as I walked down into the small cluster of white canopies. Emily Haggett, an intern for the Casco Baykeeper, saw shellfish aquaculture as an opportunity to rejuvenate Casco Bay. Victoria Boundy of the Casco Bay Estuary Partnership also saw the close linkage of the bay's health and aquaculture. “As climate change effects groundfish operations, aquaculture will be necessary for the survival of the local fisheries. This aquaculture development will only be possible with clean water,” she argued. She saw the festival as a big step forward, stating that “each industry needs to support the other, and this festival is a great way to get the message out about clean water.” This industry integration was displayed in the next table over, where Maine Seaweed Teas served samples of their locally grown, seaweed-based teas to passersby.

This optimism about the future of aquaculture continued as I walked down into the small cluster of white canopies. Emily Haggett, an intern for the Casco Baykeeper, saw shellfish aquaculture as an opportunity to rejuvenate Casco Bay. Victoria Boundy of the Casco Bay Estuary Partnership also saw the close linkage of the bay's health and aquaculture. “As climate change effects groundfish operations, aquaculture will be necessary for the survival of the local fisheries. This aquaculture development will only be possible with clean water,” she argued. She saw the festival as a big step forward, stating that “each industry needs to support the other, and this festival is a great way to get the message out about clean water.” This industry integration was displayed in the next table over, where Maine Seaweed Teas served samples of their locally grown, seaweed-based teas to passersby.

By this time, visitors to the festival began to flood the tents. Many were local residents or relatives of local residents who had heard about the event from postings on Chebeague Island. Many knew little about aquaculture before attending the event. Visitor Joyce Kuh and Nan Borod, friends from New York and Boston, were staying on the island with Joyce’s daughter, Katrina. While the three expressed enthusiasm about the future of aquaculture, Katrina cautioned that property ownership cases and climate change could threaten aquaculture development. Kristie Belesca stopped by the festival while staying with her in-laws, Chebeague Island residents. While she had little previous knowledge of the topic, she had seen her neighbor harvesting oysters which had piqued her interest. Taken up by the entrepreneurial spirit of the event, she too saw a bright future for Maine aquaculture.

As the tents began to fill up with visitors, talks on aquaculture began in the Niblic Gallery, a space located on the upper floor of the Chebeague Island Boat Yard building. A number of talks from different sectors of the aquaculture industry ensued. These talks encompassed numerous viewpoints, from the practical, business-conscious discussions of Paul Dobbins and Ocean Approved Inc. to the system-centered talk of Barton Seaver, acclaimed chef and author. Seaver directs the Sustainable Seafood and Health Initiative at the Center for Health and the Global Environment at the Harvard T.H. Chan School of Public Health. Almost all of them reflected hope for the future of aquaculture, and a strong belief that aquaculture development was essential to the survival of Maine’s working waterfront.

Ernie Burgess, a career fisherman, provided the counterpoint. In his wide-ranging and frank talk, “Aquaculture Leasing: A Lobsterman’s Perspective,” he presented the only opposition to aquaculture development that I heard at the festival. His talk focused on the issue of ocean rights. The sale of certain sections of it for aquaculture sites curtails fishermen's rights to fish anywhere on the sea, breaking an old legal tradition. Despite this contestation, he insisted that he isn’t against aquaculture development. Instead, he is against aquaculture sites leased by people who do not reside on Chebeague Island. He finished by saying that we shouldn’t turn to technological innovation to fix the problems with our fisheries resources. “We will never dominate nature,” he warned.

As my time at the festival came to a close, I joined a tour of the Chebeague Island Oyster Company. This company, founded five years ago by Bob Earnst and David Wistan, encourages fishermen to start aquaculture farms in order to diversify their revenue streams. Neither of these two founders had any relevant experience beyond casual gardening, but were heavily involved in the Chebeague Island community and sought a way to help local fishermen. “We first asked ‘What if lobstermen could diversify?’ and then we figured ‘Why don’t we try it? If it succeeds, great! If not, we can keep our day jobs," remembered David Wistan. They learned by attending aquaculture classes in the Damariscotta River, as well as by consulting fellow aquaculturalists. Now, they are weighing a potential expansion of their site, and have seen a change in the mindset of Chebeague Island fishermen. While some Chebeague Island fishermen were open to aquaculture from the start, others adamantly opposed it. Now, those fishermen who once fundamentally opposed all aquaculture have turned their ire against aquaculture sites in Chebeague Island waters owned by non-locals.

As the 3:45pm ferry approached the Island, I boarded a van with Julia Maine, a recent Bowdoin graduate and mastermind behind the festival. When I noted during the drive that optimism seemed to be the defining characteristic of both the festival presenters and the participants, the other passengers chuckled. “You should go to a lease hearing,” said James Crimp, an employee of The Island Institute. There I could hear all of the opposition to aquaculture development voiced by lobstermen, landowners, and others.

I weighed these challenges to aquaculture development over in my mind as the ferry slowly crossed back to the mainland. It was hard to imagine anything getting in the way of the brilliant and driven people that I had met at the festival. It would be easy to walk away from the festival viewing only the benefits of aquaculture development. But to ignore the warnings of people like Ernie Burgess would be shortsighted. Too many times in our nation’s history have we made well-intentioned changes to our environment only to discover that these changes have unforeseen negative consequences. Before we plunge headfirst into aquaculture development, a technology that has the potential to save Maine’s working waterfront, we must evaluate all of the potential benefits and drawbacks of such an industry. Ignoring the opinions of local fishermen like Ernie Burgess not only disenfranchises integral participants in Maine’s fishing industry, but also may have lasting consequences for the health of our environment.

See the Festival webpage for more information.