North America’s First Public Drawing Collection Surveyed at Bowdoin College Museum of Art

By Bowdoin College Museum of Art

Curated by Joachim Homann, Curator at BCMA, the exhibition builds on the foundation of Bowdoin’s strong history of collecting works on paper, stemming back to the initial gift of 141 historic European drawings to the college by James Bowdoin III in 1811. Since then the drawings collection has evolved to include nearly 2,000 unique works on paper, encompassing acquisitions and gifts from alumni, artists, and patrons. Many recent additions to the collection will be on view for the first time. Spanning from a drawing from the workshop of Raphael, to the first-ever watercolor by Winslow Homer to enter a museum collection, to works produced in the past five years by Natalie Frank, William Kentridge, and Titus Kaphar, the exhibition offers a diverse selection of masterworks from artists across a wide range of history.

“We’re delighted to have the opportunity to present a comprehensive survey of our renowned collection of drawings, which, through its distinct breadth and depth, provides rewarding insights into the evolving role of drawing over the past 500 years of Western artistic practice,” said Frank Goodyear, co-director of the Bowdoin College Museum of Art.

The exhibition considers drawing in Europe and the United States throughout time, observing how artists advanced the role of drawing in artist’s creative processes—from a primary tool to record the visual world, to a medium distinguished for its expressive qualities and immediacy in the advent of photography and subsequent technological advances in the digital age, ultimately underscoring what makes drawing different from other forms of notation.

Upon entering the exhibition, visitors will be greeted by Pharrell, 2014, Alex Katz’s seven-foot-tall portrait of the American singer and songwriter Pharrell Williams. A preparatory drawing that employs a Renaissance technique, this work demonstrates just one practical use of drawing within the artistic process. rom this starting point, the exhibition illustrates many applications of drawing in the studio, from invention to observation, to composition and recording of a finished work.

As curator Joachim Homann describes: “Rather than aiming for a coherent and systematically ordered set of reasons that compel artists to draw—a goal that seems elusive, given the widespread practice of drawing—we introduce a broad selection of works of art, and each is probed for being a record of a directed artistic intervention. Each models a different way of embedding information in a work of art and adds a new facet to our understanding of drawing, offering insights into the creative process as it shaped work in artists’ studios of the past 500 years and continues to evolve today.”

Highlights of the exhibition include:

- A double-sided drawing after Donatello’s “Miracle of Miser’s Heart,” (1505–1520) from the workshop of Raphael, reproduces figurative groups from Donatello’s bronze reliefs for the high altar of Sant’Antonio, Padua.

- A rapid sketch by Peter Paul Rubens, The Death of Dido (1600–1603), depicts the first Queen of Carthage, in despair over Aeneas’ departure, falling on a sword.

- The End of the Hunt (1892) was the first Winslow Homer watercolor to enter a museum collection, capturing the untamed nature of the Adirondacks.

- Alberto Giacometti’s portrait of his friend James Lord, sketched on the last page of a political review by French intellectual and literary figure Georges Bataille from 1948.

- Michelle Stuart’s record of the ground outside her home, entitled Little Moray Hill (1973), produced by placing the paper directly on the dirt and rubbing on it with graphite to transfer the most minute topographical distinctions.

- Ed Ruscha’s Fix (1972), which completely obliterated the traces of the artist’s hand in a drawing with gunpowder on paper, only to evoke verbally the medium’s ability to record movement in permanence.

- The Jerome Project (2015) by Titus Kaphar combines the portraits of three young black men whose tragic deaths prompted a national conversation around racial profiling, policing, and gun violence: Trayvon Martin (died February 26, 2012), Michael Brown (died August 9, 2014), and Tamir Rice (died November 22, 2014), which outlines the subjects’ faces in white chalk on asphalt-coated roofing paper.

The Museum is pleased to announce a series of exhibition related public programs throughout the summer, with events ranging from a group discussion on the history and impetus behind collecting, talks on notable artists, the Museum’s historic holdings, and the importance of drawing to an artist’s practice. Highlights include:

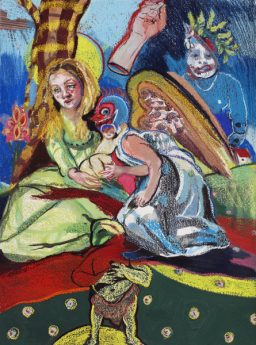

- Why Draw? artist Natalie Frank, creator of widely exhibited and critically acclaimed illustrations of the “unsanitized” fairy tales of the Brothers Grimm, will visit the Museum to discuss the implications of her works for women, their bodies, desires, and fears on May 2.

- Museum Co-Director Frank Goodyear will lead a discussion on the drawings of Winslow Homer and their historic importance in the Museum on July 18.

- George Keyes, former curator at the Detroit Institute of Art, will host a workshop on the practice of collecting Old Master works and the history of studying European prints and drawings on July 27.

- Artist Andrea Sulzer will lead a workshop called Tracing the Artist’s Hand, including both hands-on activities and a discussion on the changing approaches to mark-making on paper on August 24.

- Joachim Homann, the exhibition curator, will analyze the use of the figure in the European avant-garde, focusing on master works by Egon Schiele, Pablo Picasso, and Henry Moore on August 25.

- An evening dedicated to changing artistic and cultural attitudes toward paper with Ruth Fine, former curator, National Gallery of Art and Marjorie Shelley, Conservator in Charge, Works on Paper, The Metropolitan Museum of Art, on August 31.