With Neighboring Marine Labs, Bowdoin Commits to Longterm Gulf Project

By Rebecca Goldfine

Teaming up with marine research centers up and down the coast, Bowdoin College has embarked on a longterm study to better understand how the Gulf of Maine is responding to climate change. Scientists report that the Gulf of Maine is heating up more rapidly than 99 percent of the world's oceans, impacting natural systems and coastal communities in Maine.

The relatively new group, called the Northeastern Coastal Stations Alliance, or NeCSA, includes Hurricane Island Foundation for Science and Leadership, Bates College, Bigelow Laboratory for Ocean Sciences, Schoodic Institute, Gulf of Maine Research Institute, and Shoals Marine Laboratory. Bowdoin contributes two sites to the alliance — its Schiller Coastal Studies Center in Harpswell, Maine, and the Bowdoin Scientific Station on Kent Island, in the Bay of Fundy.

The dozen NeCSA organizations dot the coast from the Maine/New Hampshire border to New Brunswick, Canada, a geographic reach that lets scientists monitor a wide swath of the Gulf coastline. "We anticipate both joint publications and trans-disciplinary findings that propel scientific knowledge and understanding of environmental change in the Gulf of Maine particularly, and more generally in the coastal zone," the alliance says in a statement.

Bowdoin College has taken a leading role in developing the alliance's research objectives, according to Dave Carlon, who directs Bowdoin's College Coastal Studies Center. In 2014, Carlon and Visiting Assistant Professor of Biology Sarah Kingston — along with several Bowdoin students — began collecting temperature data in three intertidal sites: at the Coastal Studies Center and on Kent and Hurricane Islands. They also began to statistically quantify intertidal community structure at each site. In other words, they are counting and identifying the diversity of plants and animals living on rocky shores between the tides.

In the fall of 2015, at a meeting for NeCSA members, the alliance formally adopted these two preliminary scientific objectives, vowing to monitor how they change well into the future. In the future, if there is adequate funding, the alliance would also like to test the ocean water's pH levels and acidity, Carlon added.

Once a year, in late summer, Carlon and Kingston work with the dozen or so students who enroll in Bowdoin's Marine Science Semester to collect the intertidal data. Just three years into this project, they have noted significant changes, and intriguing variations among the three sites. Carlon says the changes in temporal and spatial patterns provide the foundation for years of student honors projects and independent studies.

NeCSA members are not unique in their quest to collaborate. More marine labs across the country and world are joining efforts to document the effect of climate change on marine ecosystems. "Other collections of marine stations and labs are thinking about how to use their sites to collect data over long timeframes," Carlon added. Leading the way is the CeNCOOS network on the West Coast, which is monitoring ocean acidification using both offshore buoys and data collected at marine laboratories.

So far, the NeCSA project has received a small planning grant from the National Science Foundation and a SeaGrant development grant to equip more stations with temperature data loggers. But Carlon notes that a strength of NeCSA is that the data collection is relatively inexpensive, particularly with the help of students and volunteers. "This is huge advantage in times when federal science funding for studying climate change is uncertain," he said.

The technology is also not too expensive: water temperature gauges cost roughly $100 apiece. They can collect water temperatures every 30 minutes for a year before scientists download their data. The equipment does, however, require replacing every three years.

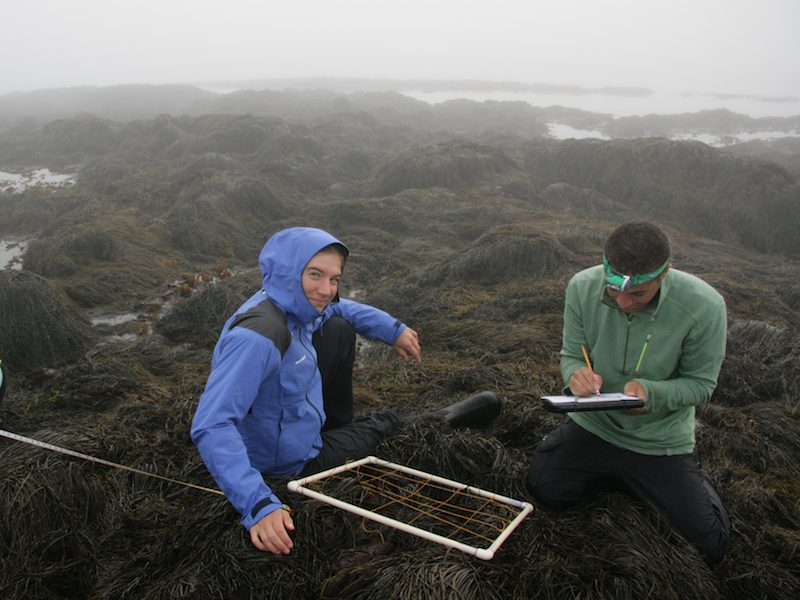

To quantify community structure in intertidal zones, Carlon and his staff have installed permanent 100-foot linear transects at each of the sites. The ends of transects are marked by steel pins so they can be relocated each year. Students work along these transects, identifying organisms and counting their abundance in square PVC frames. Students learn to identity the species of a diverse seaweed community, and invertebrates such as crabs, mussels, and barnacles.

“It's a great learning-by-doing experience for students,” Carlon noted. “They are learning the principles of marine ecology, experimental design, and can see first hand how climate change is impacting the Gulf of Maine. They are contributing to a pioneering long-term study that will grow more important as the Gulf continues to change. It excites them."