Ambassador Laurence Pope '67: American Security and the Revenge of Globalization

By BowdoinI have been warned by the Bowdoin Marines against indulging in nostalgia. My father, who like most men and women of his time, had little patience with looking back, would be the first to agree with this injunction. But I do want to call to mind briefly his generation of Bowdoin Marines, if only by way of setting the scene for a discussion of our security in this age of globalization and its discontents.

It is easy to forget, in light of what was to come, that a deeply entrenched pacifism was part of their inheritance, the legacy of the Great War fought to end all wars — the horrors of the Somme and Verdun; of poison gas; and the futile sacrifice of millions to Moloch, the God of battle. War was anathema to their generation. At a celebrated debate at the Oxford Union, the motion that “in no circumstances will this house fight for King and Country” had passed by a two-to-one margin. They read “All Quiet on the Western Front,” “Goodbye to All That,” and the bitter poets of the trenches, Siegfried Sassoon and Wilfred Owen, who denounced Horace’s Old Lie, that it is sweet and right to die for one’s country. Returning to Bowdoin from a junior year in France cut short by the outbreak of war in 1939, Everett Pope wrote: “May it be only the plans and not the bodies of American youth which are broken by this conflict.”

We forget, too, that the isolationist America First Committee was founded not by the pro-Nazi Charles Lindbergh, who became its principal spokesman, but at Yale, by Kingman Brewster, later the president of that institution. Its 800,000 members included a future president, Gerald Ford, and a future Supreme Court justice, Potter Stewart, as well as the Harvard undergraduates Joe and Jack Kennedy, sons of President Roosevelt’s ambassador to Great Britain. Jack contributed $100 to the cause, a considerable sum for even the son of a wealthy father. In a 1940 letter to President Roosevelt, three hundred Harvard undergraduates vowed that “never under any circumstances will they follow in the footsteps of the students of 1917.” A scornful Franklin Roosevelt derided them as “shrimps.”

Pearl Harbor changed all that of course, and the same students who had been isolationists served their country in war. Joe Kennedy died, and Jack was lucky to survive the sinking of his patrol boat. Millions of men like my father and Andy Haldane resigned themselves to war as a necessary but grim business. There was little good about the “good war” for them. The term “trained killer” used in the latest “Killing” book from the Bill O’Reilly factory of potted history to describe 2nd Lieutenant Everett Pope is not exactly apt, but they became skilled combat leaders and proud Marines. The memoirs of the men who served under them attest to that. There remained a cultural divide between young company level officers from colleges Yale and Princeton, as well as Bowdoin, and the veterans of the prewar Marine Corps of spit and polish and puttees, some of whom believed that the courage and élan of Marines could defeat heavy weapons with prepared fields of fire.

After the invasion of the island of Peleliu in September of 1944, where the butcher’s bill was as bad or worse than anything at the Somme, my father annotated his copy of verses by Siegfried Sassoon about an incompetent general who sent his men to their deaths, with the name of the Commanding General of the 1st Marine Division. To Dean Paul Nixon, he wrote of the death of his classmate Andy Haldane, also a company commander during that battle, that:

He died as he had lived, at the head of his company where the fighting was the heaviest. He was a remarkably fine leader, and his abilities were well-known throughout the Division. I had spoken with Andy a few days before he was killed, as our companies paused near each other. He was in good spirits, but sick of the killing, as were all of us.

When the war was over, those who had survived returned to civilian life with “the high resolve that this shall not happen again,” in the words of the first honorary degree the College awarded to Dad in 1946. In the three score and ten years which separate their world from ours, we have often found ourselves at war. But while peace has been elusive, the international system they built has endured.

Here a Latin tag is appropriate: si monumentum requiris, circumspice — if you seek their monument, look around you — not just at the understated granite memorial between the library and the art museum to the Bowdoin graduates who died in World War II, Korea, and Vietnam, with eleven names from the Class of 1941 alone, and an inscription from Longfellow about the pity of war. For we live in the world they built. The Marshal Plan in Europe, the United Nations, the World Bank and the IMF, and our alliances from NATO and to the security treaty with a democratic Japan, were not simply expressions of American idealism, though there was some of that. They were put in place in the postwar years by practical men who rejected the isolationism and narrow nationalism of the 1930s, which had led the world to disaster, and who were determined to ensure that the democratic values they had fought for could flourish.

The postwar era can be divided into two parts. Our methods in the so-called long peace of the cold war do not always bear close examination, but it ended with the collapse of the Soviet empire in 1991, and for a brief moment it appeared that liberal democratic values would be ascendant everywhere, in a triumphant neo-Hegelian end of history. In Tienanmin Square in 1989, brave crowds gathered around a model of the Statue of Liberty; in 1991, Boris Yeltsin mounted unsteadily atop a tank in Red Square. Gordon Adams of Brunswick, one of the country’s leading experts on national security and the defense budget who is here tonight, recalls that as recently as a decade ago there were twenty agencies of the U.S. Government involved in democratization programs in Russia. I spent some of that time myself preaching — the word is not too strong — democracy and free elections to bemused Africans. By the advent of the new millennium, it appeared that the principal threat we faced was whether computers all over the world would collapse, unable to cope with the turnover of digits.

The attacks of 9/11 2001 changed all that, shocking the country into allowing a cabal of neoconservatives — with, it should be recalled, considerable support from liberal internationalists — to test the limits of American power. Their attempt to remake an imaginary place called the Greater Middle East with the 2003 invasion of Iraq showed that while our military power was unchallenged, it did not follow that democracy would emerge in its wake. Our senior military leaders too, misreading the easy victory of the 1991 Persian Gulf War, have had to relearn in the crucibles of Iraq and Afghanistan the ancient lesson that warfare is about politics, not engineering.

In the years since 9/11, our national security apparatus has been radically transformed. The post-9/11 Authorization to Use Military Force, granted without much debate to the president by Congress, remains in force some fifteen years later. The burden of our nation-building wars in Iraq and Afghanistan has been borne almost entirely by the extraordinary professional military force we built after Vietnam, with a disproportionate share of the casualties from rural towns and the working class, while the rest of us carried on as usual. The defense department budget has roughly doubled, and so has the intelligence budget, creating a military-intelligence complex not unlike the military-industrial complex Dwight Eisenhower warned against in his farewell address.

The role in this so-called war on terror played by special forces deployed around the globe would be unrecognizable to a pre-9/11 observer of our military posture. An undeclared war, it is none the less real for that. The other day, just before the inauguration of a new president, The New York Times reported on an inside page that in what was described as a final strike in Libya, B-2 bombers launched from a base in Missouri had dropped over 100 targeted bombs, with additional strikes from drones based in Sicily, killing more than 80 ISIS fighters. In December, in an effort to establish a record for posterity that such attacks were carried out in compliance with international law, the outgoing administration published an elaborate legal justification for them — a document to which the new administration is unlikely to pay the slightest attention. A few days ago our special forces attacked a terrorist base in Yemen, killing terrorists but also women and children, with the loss of two Americans — one a highly skilled member of the attacking force, and the other an eight-year-old child.

As a consequence of the war on terror, as former Secretary of Defense Bob Gates has said, our national security apparatus has been militarized to the point that the use of force is often a first reflex, not a last resort. Under the presidency of Barack Obama, late of Harvard Law School, that was one thing; under the presidency of Donald J. Trump, late of reality television, it is likely to be quite another.

One aspect of this militarization has been the marginalization of the State Department, our foreign ministry, and our career diplomatic service, an institution in which I spent thirty years. The Foreign Service of the United States, its full title, provides the permanent staff that allows the State Department to continue to function through changes of administration, most of our ambassadors, and all of their deputies. The Foreign Service remains a reservoir of talent available to the president and the secretary of state; the opposition in its ranks to the administration’s ill-considered ban on immigration from some Muslim countries, revoking visas already granted, shows that its basic reflexes remain sound. But its role in today’s militarized national security process is much diminished. Our time together is too brief to review the causes of its decline. I wrote a small book about it a few years ago. Some of it has to do with a vastly expanded temporary White House staff. I can illustrate the problem quickly. When I returned briefly to active duty to run the Embassy in Tripoli in October of 2012 after the murder of our young ambassador and three of his colleagues, I had been out of the business for over a decade. Both of the senior State Department officials I worked with most closely, the assistant secretary for Near Eastern affairs, and the assistant secretary for diplomatic security, were also retired officers of my vintage. When a career institution is unable to fill such key positions from its active ranks, something is wrong.

Diplomacy is a murky and unsatisfactory term, coined about 1800 when it displaced the far more intelligible “negotiation.” Americans have never liked it. As war clouds with England gathered before 1812, stout yeomen at New England town meetings denounced what they called “the diplomacy of courts.” Nor is what contemporary American diplomats do well understood. Running an embassy these days involves responsibility for our ubiquitous military and intelligence operations, not simply the management of the bilateral diplomatic relations they often complicate. The authority of an ambassador derives from powers granted by the president, not the secretary of state. In times of crisis Washington may try to dictate, using what in military circles is known unfondly as the seven thousand mile screwdriver, but an ambassador in full possession of her portfolio will rarely be overruled. Most of what I did in Libya involved intelligence, military, and law enforcement operations. On one occasion when I did receive an instruction to deliver a message from the president, one he probably never saw, I should have disregarded it. The skill and competence of the Foreign Service Officers who decide who will enter the country, who represent us to the world, who staff our foreign ministry, and who advise the president and secretary of state, matter as much to the national security as a carrier battle group — more, some would say.

Over the years Bowdoin graduates have had distinguished careers in the Foreign Service. Chris Hill, class of 1974, served as Ambassador to Iraq; David Pearce, class of 1972, recently stepped down as Ambassador to Greece. Tom Pickering, class of 1953, who has served as ambassador to six countries and the UN, is the pre-eminent diplomat of his generation. He headed the accountability review board convened by the State Department after Benghazi, and the subsequent politically motivated investigations by various committees of the Congress added nothing material to its findings.

Diplomacy is coterminous with what political scientists like to call post-Westphalia nation-states, after the European treaties ending religious wars in 1648. In recent years, advanced thinkers in Silicon Valley and elsewhere have predicted the disruption of this world of nation-states by the inexorable forces of globalization. Theorists like Professor Anne-Marie Slaughter of Princeton, who was Hillary Clinton’s policy planning director at the State Department, a position created by George Marshall for George Kennan, have argued that the vertical paper-based hierarchies of the nation-state would be disrupted by digital networks operating above and below the state. In such a world there would be little need for traditional diplomats. Professor Slaughter presided over an exhaustive reform project at the State Department in which the Foreign Service was only mentioned in the context of the need to make it easier to enter without an onerous examination.

Increasingly it is clear that these theorists of the decline of the analog nation-state in an age of digital networks had it precisely backwards. We are seeing instead what might be called the revenge of globalization. The world is not flattening out into a homogeneous liberal economic and political order. On the contrary, tectonic forces of globalization are generating new mountains and valleys along old stress fractures. The United Kingdom, three centuries old, is in danger of dissolving into its ancient components. The European Union that promised a continent “whole and free” only a few years ago no longer seems the wave of the future. Nationalist politics are on the rise in democracies from Poland to France, as well as in autocracies from China to Russia. I would argue that in part at least the collapse of the state system in the Middle East and the rise of a so-called Islamic State on its ruins is a consequence of the rage generated by an atavistic sense of loss and dislocation attendant to globalization. It seems to be the case that as we are forced together into a globalized information grid, we cling more stubbornly to the things that make us ourselves. It is a phenomenon we are only beginning to understand, and it awaits its theoretician, a Marx or an Adam Smith for the information age.

This phenomenon was evident in our endless presidential election campaign, when a skillful demagogue exploited the fears generated by globalization and promised to reverse the process. It is notable, too, in retrospect how much of that campaign was conducted in and about cyberspace: endless pettifogging arguments over emails and tweets; Russian interference in cyberspace favoring one candidate over the other; paid internet trolls peddling lies — all of it created an aura of unreality and postmodern distance in which the truth was a casualty. In such a climate, the Biggest of Lies can leave a residue of doubt even after they are debunked, like the attempt to delegitimize the country’s first black president by suggesting that he was not an American by birth, or the baseless allegation that millions of illegal immigrants voted, undermining the very basis of our democracy. It is no accident that the winner was a star of Reality Television, a theatrical genre which is anything but real, while the loser was a thoroughly analog politician.

I do not pretend to be able to see clearly into the world of the 21st century which will be created by these restless forces. I do know that it will present unprecedented new challenges to American security, and that without American leadership a world subject to the pressures of globalization will not order itself. The institutions of the postwar world need reform, not wholesale rejection. The UN Security Council reflects the state of things in 1945 undermining its moral weight; NATO could do with more burden-sharing. Instead of simply seeking dominance in cyberspace with the creation of a new military command, we could be leading an effort to negotiate international codes of state conduct, before the internet degenerates into a global battlefield. Climate change, and terrorism too, require new diplomatic responses. New doctrines of international law have emerged like the so-called Responsibility to Protect, which makes it the duty of all states to intervene across borders when human rights are violated, weakening the post-Westphalia respect for national sovereignty. Can these extraterritorial doctrines be a guide for American policy when we would not permit their application by others to us? What are the proper limits of humanitarian intervention? In a world of states, what is the answer to the old question, who is my brother?

The technical name for the grand strategy we have followed in the postwar period, with aberrations, is offshore balancing, and for the most part it has served us well. Not much of a clarion call, you will not hear it invoked in soaring speeches. Associated with the so-called realist school of foreign policy, it has often united liberal internationalists and neoconservatives too, despite sharp tactical debates over the years. In a sense we have our adversaries to thank for its success. Russia’s aggression in Ukraine has given new relevance to the Atlantic Alliance, which only a few years ago looked as if it had lost its reason for being. China’s territorial pretensions in the international waters of the South and East China Sea have galvanized a coalition that includes not just traditional American allies like Australia, South Korea and Japan, but Vietnam, a coalition which is underwritten by American naval power. When we have stuck to a grand strategy based on alliances, we have been successful; when we have departed from it, as in Vietnam and in Iraq, we have come to grief. It is a strategy of engagement in the world motivated not by an unfocused humanitarian idealism — there has been too much of that in our rhetoric perhaps, suggesting to some that we are being taken advantage of — but by hardheaded realism and pragmatism. Archimedes said he could move the world, given a place to stand; our international alliances are the ground we stand on.

Now this grand strategy is being casually abandoned, tweet by capricious tweet. In one of his first pronouncements as president, at an appearance at CIA headquarters no less, the chief magistrate of our venerable republic declared that we should have simply stolen Iraq’s oil, like a pirate state, leaving open the possibility of doing so in the future. He has gratuitously insulted the Prime Minister of Australia, an American ally for generations. He has derided those who invoke international law as fools. He appears to believe, as Thucydides tells us Athenian envoys said to the island state of Melos before they killed its men and enslaved its women and children, that we live in a world where the strong do what they can, and the weak suffer what they must. It is worldview identical to that of Vladimir Putin, which may be one reason why the Russian autocrat is his favorite foreign leader. They both forget that the Peloponnesian wars ended with the subjugation of Athens by a stronger rival.

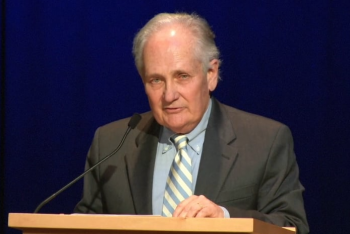

These dark instincts will involve us in armed conflict sooner than we imagine unless they can be restrained. In that regard Trump’s cabinet appointments, especially at the Department of Defense, offer some hope. During his confirmation hearing as Secretary of Defense, General James Mattis, USMC, stressed the importance of our alliances and commitments,: “History is clear,” he told the Senate: “nations with strong allies thrive and those without them wither. Strengthening our alliances requires finding common cause, even with imperfect partners; taking no ally for granted; and living up to our treaty obligations. When America gives its word, it must mean what it says.“ At the hearing in which he was introduced by a former Secretary of Defense, Bill Cohen of the Bowdoin Class of 1962, Mattis promised to “reinforce traditional tools of diplomacy … using military force only when it is in the vital interest of the United States, when other elements of national power have been insufficient in protecting our national interests, and generally as a last resort.” These are the lessons of Iraq and Afghanistan, and I know General Mattis well enough to believe that he can be counted on to insist on their observance.

But the President’s immediate entourage is dominated by men with a radically different world view. Mike Flynn, the national security advisor, is an Islamophobe whose ties to Russia have been under investigation. Steve Bannon, Trump’s chief strategist, is an extremist who is now by Executive Order a principal of the National Security Council — a document The New York Times reports today the president failed to read before he signed it — even though the 1947 Act creating the NSC requires that its principals be confirmed by the Senate. Flynn and Bannon are spoiling for a splendid little war they can use to showcase their willingness to use force. An occasion may present itself in the Persian Gulf, where Iranian and American naval forces coexist uneasily, especially now that Iran has been “put on notice “ after a provocative missile test, in an all caps Tweet no less, the Internet equivalent of shouting. A conflict that can be portrayed as a war against Islam would best suit the demagogic purposes of Flynn and Bannon. If it involved Iran, it would probably make the painstakingly negotiated nuclear agreement a dead letter — an objective Bannon and Flynn share with Iranian radicals, who agree with them that a war between Islam and the West is inevitable.

I would like to be more hopeful. I am feeling a bit like Cassandra, a bore who continued to repeat the same dismal prophecy until she lost her audience. She could see the future; it is just as well that I can’t. Things are often not as bad as we think; sometimes they are worse. When the topless towers of Ilium were eventually toppled, as Cassandra never ceased to warn, it was an inside job. We have rarely been as secure in the world as we are today, alarmist rhetoric about Islamic terror notwithstanding. If by our own folly we abandon the global norms of the international order we led the way in building, with a return to the blinkered America First nationalism of the 1930s, this time in a world with nuclear weapons, we will have only ourselves to blame. Bismarck may have said, ”A special Providence protects fools, drunkards, small children and the United States of America,” but it would not be wise to test that proposition.

Let me close with a few words to the undergraduates present. My father disliked the term “greatest generation,” which publicists invented years after World War II. Every generation faces its own challenges, he would say. When the Bowdoin students of my generation graduated, the Vietnam War was raging. I avoided the draft in the Peace Corps and in the Foreign Service, ending up in Vietnam anyway, though in relatively comfortable circumstances. In preparation for this talk, reading Joseph McKeen’s inaugural address as Bowdoin’s first president I was struck by this acute summary of my own state of mind as an undergraduate a half century ago: “The volatility of a youthful mind frequently gives rise to eccentricities, and an impatience of the most wholesome restraint.” Other made different choices, and in some ways we are still defined by the choices we made back then.

What we remember from McKeen’s inaugural address is of course another passage: “Every man,” he said, “who has been aided by a public institution to acquire an education, and to qualify himself for usefulness, is under peculiar obligations to exert his talents for the public good.” (Every woman and every man, he meant to say.) Bowdoin Marines, of whom there were two in the class of 2016, have chosen to serve the public good in the profession of arms. They would be the first to say that there are other ways. When McKeen spoke, our Republic faced the danger of extinction. A decade later, Washington was occupied and burned by an enemy force. Today we face a different threat, this time from within — the ultimate threat perhaps, from ourselves.

Even in these cloistered halls you may be called upon to resist it, and the choices you make will define you, just as they defined my father’s generation and my own. So let me make one suggestion: no matter where your studies take you, take a moment to reflect on the right uses of American power in the world. It will not be a theoretical proposition for your generation. Be skeptical of those who portray the United States as the root of all evil. That is the other face of American narcissism, which makes the outside world into a stage set for a drama in which we are the only actors, fashionable in some parts of the academy — not at this distinguished center of liberal learning I trust. Conduct a thought experiment in which you imagine a world with diminished American influence Would it be a better place? Consider too the implications of the Hobbesian world of Trump and Putin, in which every nation is set against the other in a naked struggle for dominance.

But be just as skeptical of politicians who preach about that “shining city on the hill,” and boast that we are an exception to the original sin of history. It is supposed to be a quote from a homily delivered in 1630 by Governor John Winthrop to his flock on the sloop Arabella, on the way to found the Massachusetts Bay Colony. But when Winthrop said “we shall be as a city on a hill” — no “shining,” that was added by Ronald Reagan — it was not a boast but a warning, an invocation as his congregation knew, but we have forgotten, of the Gospel of St. Matthew: “A city on a hill cannot be hid.” “If we shall deal falsely with our God in this work,” warned Winthrop, “we shall shame the faces of many of God’s worthy servants … and cause their prayers to be turned into Curses upon us, till we be consumed out of the good land whither we are going..

This is still a good land, despite its imperfections. It has never ceased to be a great one. In the restless 21st century that lies ahead, it will be up to your generation to make sure that it stays that way. As you do, you could do worse than to be mindful of the legacy of Bowdoin’s Marines.

Thank you.