Black Lives and Blue Uniforms: Police Speak to Students

By Rebecca Goldfine

Two law enforcement officers visited Bowdoin recently to speak with students about what it’s like to do their jobs in the context of today’s charged conversations about race and policing. The officers acknowledged the complexity of race and racism, agreed that race impacts their line of work, and offered ideas about what could be done to reduce police killings of civilians.

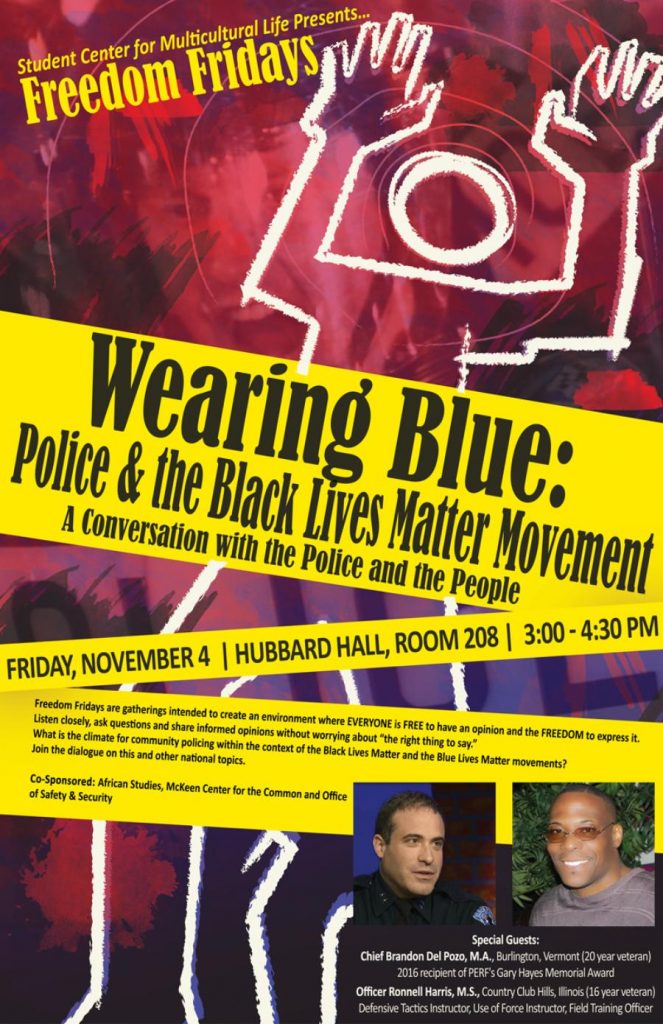

The event — “Wearing Blue: Police and the Black Lives Matter Movement” — was part of Bowdoin’s Freedom Fridays series organized by Benjamin Harris, director of the Student Center for Multicultural Life. Harris invited two officers who work in different parts of the country to describe how policing gets done in demographically distinct regions. He urged students to feel free to ask questions and offer opinions.

Before Brandon Del Pozo became chief of police in Burlington, Vt., he worked for 19 years in New York City as a police officer. Ronnell Harris has 16 years of experience in the police force, working in the ethnically diverse Chicago Heights neighborhood before moving to his current position as an officer in Country Club Hills, Ill. While Burlington is predominantly white, Country Club Hills, which is outside Chicago, is 90 percent African American.

Both men responded to a question about how they have been affected by media stories about police killings of African Americans. Harris pointed out that not every officer who commits such an act is acting on prejudice, and he argued that each case of police violence should be judged by its own facts and circumstances.

Del Pozo noted that the actions of a few officers who appear to unjustifiably gun down black people do not reflect the thousands of police who do their jobs without any such incident — and work hard to avoid them.

In the United States, he said, “there are 17,000 different police agencies—each of them answering to their own political constituency—and 765,000 officers.” He added, “Each police department is unique.”

Del Pozo pointed to his former employer as an example of a department that stands out from others. The rate at which the New York Police Department shoots civilians is far below the national average. According to the Washington Post and the Guardian, approximately 1,000 people in 2015 died at the hands of police in the US. After doing some calculations, Del Pozo said, “If the police in the rest of the country killed people at the rate that NYPD killed people…that would be 650 Americans who would still be alive.”

The NYPD has adopted some distinctive practices to reduce civilian killings, such as never shooting at a car unless its occupants pose a direct threat, using nonlethal methods instead of firearms to subdue unruly people, and deploying robots to go into dangerous situations before police, Del Pozo explained. He said that at the moment, there are no national standards for policing practices.

Despite the unevenness of policing across the United States, Del Pozo emphasized that Americans have the right to demand that their local police department, and other agencies, do what they can to “reduce bad outcomes for them and their fellow citizens.”

Del Pozo and Harris said much of the responsibility for averting these bad outcomes rests on fellow officers and police chiefs. Harris recounted as an example a time when he received a dispatch alert from a worried mother. While she was not at home at the time, the mother said an unwanted man was in her house with her daughter. When Harris and his partner arrived at the home, they spoke to the adult daughter who reassured them she was fine. Harris got ready to drive away, but his partner barged into the house and demanded the man leave, creating a charged and unpredictable situation. That officer was eventually fired.

“You have to weed some [of these officers] out,” Harris said. “In any profession, some people don’t cut it. If you have a person who is a time bomb, it’s only a matter of time before it blows. The signs are there.”

Both men addressed the difficulty of separating race from police work. Del Pozo said that race is entangled with class in this country and that police end up spending more time in poorer communities—which are more often minority neighborhoods—than wealthier ones. “When you have single-family private homes with back yards, you’re less likely to get noise complaints and allegations of drug use,” he said. While a guy smoking marijuana on a stoop or in a hallway of an apartment building might annoy his neighbors, no one cares if the guy next door lights up a joint on his back deck.

Once the police get called to check out a complaint, they will likely “start doing policy things,” Del Pozo said, such as stopping cars for traffic violations or pulling over if they see someone urinating in public or doing drugs.

That is not to say police officers don’t operate with implicit, or even explicit, biases, Del Pozo continued. Studies have shown that people are more likely to feel threatened by a black man than by a man of another race. “We live in a racist system,” Harris added. “It’s a disease. Do I think racism is a factor in policing? I think it is. That’s not just the officers’ fault, it’s the entire society we live in.”

A student asked whether having more or less guns would help police. Del Pozo answered that “so much of what is troubling us in American culture today is made more acute by guns.”

He pointed to New York’s relatively strict gun laws as having had a beneficial effect on the state and its citizens. “As civic-minded people, one of the biggest challenges going forward in America is making sense of the huge mess that is our gun situation,” he said. “If we could get to the rate of gun possession of Scotland, which is like zero, we’d be in much better shape. But the road there seems impossible now.”

Harris, who said he thought it was OK for civilians to have guns if they were educated about them and behaved responsibly with them, said that the possibility of arriving at a scene where people might have guns always puts officers on heightened alert.

As he travels to a call with a code like 10-32—which indicates that guns may be involved—Harris uses calming techniques he’s mastered through his martial arts practice. “I start breathing first,” he said. “Like right before a test, I go into breathing mode. I call it tactical mode. Right away I want total control over me.”

Del Pozo urged the students to consider their stance on guns and gun control laws: “As Americans, you have to figure out what kind of country you want to live in and how many guns you want in that country.”