Refugees, Xenophobia, and Modern Germany Are Focus of Bowdoin Embassy Grant

By Tom Porter

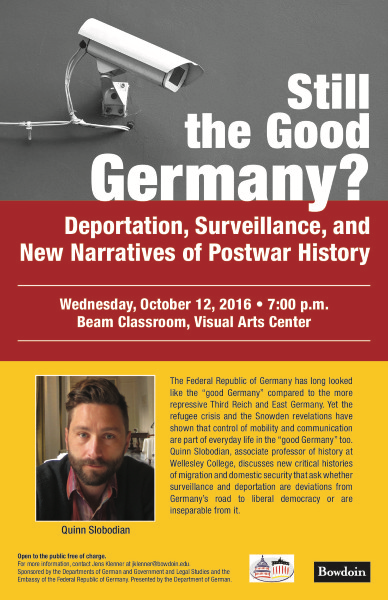

Bowdoin College has been awarded a grant sponsored by the German embassy and funded by that country’s foreign ministry. It supports a program that examines aspects of German politics and culture; this year’s theme is “Germany meets the US.” The project features a guest lecturer, classroom events, a film screening and conversation, and runs through the end of the semester. It got underway October 12, 2016, with Wellesley College Professor Quinn Slobodian’s talk, “Still the Good Germany? Deportation, Surveillance, and New Narratives of Postwar History.“

Deportation and surveillance in modern Germany

Slobodian’s lecture challenged some of the assumptions about modern Germany and the West German postwar nation that preceded it. Adopting initially a slightly humorous tone on what is undoubtedly a serious subject, Slobodian described how a somewhat “boring narrative” of recent German history had triumphed, telling the story of how the country became “normalized” or “civilized”, especially when compared to the dark days of the Third Reich or the repressive East German regime that followed.

Slobodian’s aim was to produce a “counter narrative to the essentially self-congratulatory story of Germany’s successful westernization.” In other words, Germany is not quite the model nation it seems. The country’s liberalization, he said, had also led to “a rapid expansion of the capacity of the government to amass data on the lives of residents of Germany and the expansion of the police power for it to take action on this data.”

In the same way that America’s National Security Agency was found to be spying on its citizens, said Slobodian, so too have been the German authorities, particularly on non-EU citizens, mostly refugees. He described how the West German surveillance programs of the 1970s, which were expanded significantly to fight left-wing terror organizations like the Baader-Meinhof Group, were followed more recently by programs designed to surveil non-Europeans in Germany and to deport those suspected of being connected to terrorist groups. The result is a notable increase in deportations, with 50 percent more people being turned away at the border during the first six months of this year than over the whole of 2015—an apparent departure from Germany’s initial “open door” policy towards refugees.

Slobodian said defenders of the “surveillance and deportation” approach claim it is justified by the need for a democratic state to defend itself against external threats. Some also argue that surveillance should be regarded as a social contract, said Slobodian: “We submit to counting, measurement, photography, scanning, and tracking, in exchange for benefits offered by the state.” But, he went on to point out that in modern Germany, this equation is balanced against the refugee population, many of whom find themselves in detention centers before being deported back to the war zone they were trying to escape.

However, that’s not to say that surveillance and deportation are, in essence wrong, said Slobodian. “These often startling practices are in not in fact deviations from a process of liberalization,” he reflected, “but are part of what it means to be a liberal state in the 21st Century.

In the classroom

Among those keenly listening to Slobodian’s lecture was German Professor Birgit Tautz, who plans to use the talk to discuss the refugee crisis with her students. “I try to integrate lectures such as Quinn Slobodian’s into my teaching, be it as an event which students may review, or as a way of showcasing alternate viewpoints on German cultural history. For example,” Tautz said, “in my seminar Colors 1800/1900/2000: SIgns of Ethnic Difference, we explore how ways of seeing form our ideas of identity, nationality, and migration.” While these ideas are discussed in relation to German culture, she said, a comparison with the United States, past and present, is inevitably made.

All of which ties in with the “Germany Meets US” program, said Assistant Professor of German Jens Klenner, who led the grant application process. “Bowdoin has been quite successful in getting this nationally competitive grant,” he said. “With the exception of one year, we have received the grant every year since 2009.” The German embassy sends out an annual call for applications centered around certain themes. “Over the last two years the themes have been ‘Twenty five years after the fall of the Wall,’ and ‘German re-unification.’ Applicants,” he explained, “are asked to come up with creative suggestions for how they would integrate various activities on campus under the umbrella of that theme.”

Among the events being organized for students as part of the program, said Klenner, is a forum for those preparing to study abroad in German-speaking countries. “For its size, Bowdoin has one of the biggest populations of German majors, and each year they head overseas in large numbers.” There’s another student event in December, he said, just before the end of the semester. “We will showcase a number of students’ honors theses, giving them an opportunity to present some of the original research they’ve been doing over the year,” said Klenner.

Xenophobia: a conversation

The program’s next public event is organized by the Bowdoin College Museum of Art and takes place November 10, 2016. “There will be a documentary film screening and conversation,” said Klenner, “tackling the subject of xenophobia in modern day Germany and Austria, and the rise of right wing populism as a political force on both sides of the Atlantic.”

Foreigners Out: Schlingensief’s Container chronicles a theatrical project by the acclaimed late German filmmaker and theater director Christoph Schlingensief in Vienna in 2000. “Inspired by the rise of xenophobia he was seeing, and by the popularity of television shows like Big Brother, Schlingensief created something called the ‘Container Project.’ ” The show filmed a handful of asylum seekers living inside a container in Vienna, where events are broadcast live on Austrian TV. Their fate is decided by viewers who are invited to vote on who gets granted asylum and who gets deported.

“It’s a shocking project,” said Klenner, “but also the rendering of a very powerful critique through art of what many people perceive as an arbitrary selection process, deciding who stays and who doesn’t.” At the same, he added, “the documentary also highlights the willingness and enthusiasm with which people are happy to participate. It should be a lively conversation.”