Interview with Steff Chávez-Flores ’17, student curator of the exhibition "Where do I go from here?"

By Bowdoin College Museum of Art

Steff Chávez-Flores ’17 is majoring in Government & Legal Studies and Art History at Bowdoin. Steff spent last summer at the Museum as a Curatorial Fellow and Museum Education Assistant. As a Curatorial Fellow, she developed an exhibition of vernacular photography that opens on November 3.

Will Schweller ’17, Student Assistant to the Curator, interviewed Steff about her experience as a curator.

How did the idea for an exhibition of snapshot photography come about? How did you go about selecting pieces for the show?

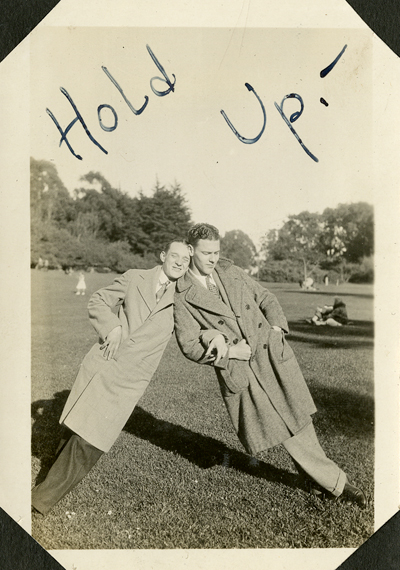

The idea for the show emerged when New York-based collector Peter J. Cohen got in touch with the Museum, and was interested in making a donation of snapshot photography. His collection is comprised of more than 30,000 photographs that were taken from 1900 to roughly 1980. Cohen began his collection by buying snapshots at street fairs—the original owners (or more likely the families of the original owners) essentially discarded the photographs by making them available for sale. Given the nature of how Cohen acquired the photographs, the photographers and subjects in the photographs are anonymous. Since his collection is so large and he thinks his images should be shared, Cohen began contacting museums all over the country offering a donation. Museums that have photographs from his collection include the Museum of Modern Art, the Metropolitan Museum of Art, the Art Institute of Chicago, and the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston. After working with these large institutions, Cohen began turning to college and university museums.

Selecting the pieces for the show was quite an endeavor. The process began in Cohen’s New York apartment, where co-director Frank Goodyear and I spent two days going through the collection. Cohen has his photographs in boxes, grouped together by themes such as ‘Watermelons,’ ‘Dangerous Women,’ ‘People on Poles & Ladders,’ ‘Tricks,’ and ‘Couples.’ Frank and I just dove into the boxes and began selecting photographs to take back to Bowdoin. We used our gut reaction to guide the selection process. We picked photographs that we liked, that were humorous, dynamic, or even evoked familiar fine art photographs. We picked ‘good’ photos—whatever that meant in the moment. We returned with 563 photographs. Once back at Bowdoin, we sifted further. Eventually, I developed an exhibition theme based on what we had, and I boiled the final selection down to 162 photographs. It was an interesting experience to go with my gut, instead of a plan. Ultimately it was best—I think that the exhibition’s potential would have been limited had we gotten to Cohen’s apartment with notions of what exactly we wanted from the photographs. We let the photographs guide us instead of the other way around.

Why is vernacular photography deserving of display in an art museum?

I think vernacular photography is deserving of display in an art museum because it’s important to put snapshots in conversation with fine art photographs. Vernacular photography shows the democratization of photography: there are billions of snapshots in existence, taken all over the world by all sorts of people. Though made with different intentions, snapshots and fine art photographs echo each other in terms of subject matter, themes, and composition. In 1974, photographer Wendy Snyder MacNeil wrote that snapshots “are today’s cave paintings, born of the same urges, rituals.” I found this to be an apt way of thinking about snapshots. Snapshots provide us an intimate, captivating way of peering into the lives of people in the twentieth-century. The twentieth-century was a chaotic, painful, and innovative period globally—artists were reacting to those circumstances, as were ‘regular’ people—and it’s interesting to see how people expressed themselves in front of the camera. Moreover, there is something fascinatingly unifying about the snapshot. Vernacular photographs are articulated using vocabulary that everyone can understand; I’ve found that people take a look at these photos and can’t help but smile.

Visit the exhibition:

Where do I go from here? Snapshots of Twentieth-Century Life

November 23, 2016 through January 1, 2017

Bowdoin College Museum of Art

Please join us for an additional program on Wednesday, December 14 at the Museum. New York collector Peter J. Cohen will join Steff Chávez-Flores and Frank Goodyear in conversation.