An Interview with Artist Hasan Elahi

By Bowdoin College Museum of Art

Elahi’s work, Tracking Transience (2003-present), is included in the current exhibition This Is a Portrait If I Say So: Identity in American Art, 1912 to Today (on view until October 23, 2016).

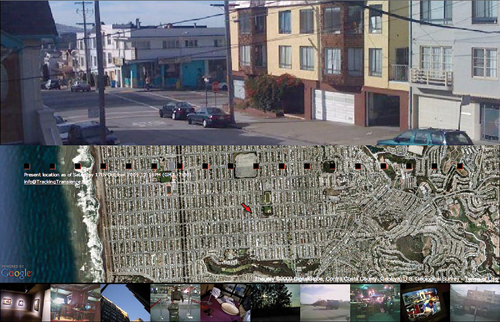

Tracking Transience responds to a serious case of mistaken identity. Erroneously added to a government watchlist in 2002, Elahi was assigned a case officer and asked to notify the FBI whenever he traveled. Turning self-surveillance into a personal archive, he began documenting his travels and activities in more detail, resulting in Tracking Transience, on view in the exhibition and also available online. The photographs and live map that document Elahi’s past and present activities disclose less about Elahi than the places and spaces that he inhabits. In this brief conversation, the interdisciplinary artist discusses how to use technology, which often overexposes personal information, in a way that ensures him more privacy.

Elahi will speak at the Bowdoin College Museum of Art on Tuesday, October 18 at 4:30 pm.

What does identity mean to you?

As someone who was born in one country and raised in another and having lived in various parts of the country, this can get a little complicated. I’m not exactly sure I have a good answer for this other than that I know it’s constantly changing and evolving.

This Is a Portrait If I Say So: Identity in American Art, 1912 to Today is an exhibition about abstraction in portraiture. Had you considered Tracking Transience to be a portrait before the exhibition? Have new meanings of the work emerged for you as a result of it being included in a show about abstract portraiture?

I think the entire concept of portraiture has changed drastically since the emergence of the selfie era. What I’m doing isn’t that different from people taking selfies. But instead of pointing the camera at me, it faces outwards and the collection of images provides a window into my “self” as it wanders through and interacts with the world. I think a key difference is that the work takes place online and the Internet is a two-way form of communication, meaning we are both consumers of information as well as producers of it. We cannot be just part of one and not the other.

One concept that comes up regularly in discussing the show with visitors is the idea that the meaning of art may change over time. Tracking Transience spans a number of years and is updated constantly. What does this work mean to you today, both in terms of your personal identity, and our current sociopolitical landscape?

I’ve been working on this for 14 years—nearly a third of my life. I’m still amazed at how quickly our culture accepted this practice as normal. When I first started this project, people thought I was insane. Why would anyone tell everyone what they were doing at all times? Why would anyone want to share a photo of every place they visited? My friends would look at me strange when I’d pull out my camera to take a picture of my meal. These days, we don’t think anything unusual about it. What I’m doing is no longer just an art project; creating our own archives has become so commonplace that we’re all — or at least hundreds of millions of us — doing it all the time. Whether we know it or not.

In your TED talk about Tracking Transience, you discuss the way in which flooding the system with personal information that is accessible to everyone diminishes the value of such information as an asset to government surveillance programs. What do you want viewers to take away from this work regarding their own agency in the ownership of this type of information?

It’s pretty clear that the technology that has made our daily lives much more convenient and will certainly not go away. We’re not going to go back to a society without cell phones, ATM cards, EZ-Pass tags, grocery discount cards, cameraphones…

Facebook and other social networks are just an extension of all these things that track us on a daily basis, not to mention every click that we make on the Internet. What we can do is to try to shape the future of how we plan to live with these technologies. We shouldn’t be afraid of them, but we should instead use these technological developments to our advantage. Also in my case, by disclosing a large amount of information, I can potentially correct future misinterpretations of me.

I live a very private life and the project is very much about identity management. There is certain information that you think would be rather easy to find about me, yet you most likely won’t find it online, like where I went to school and what kind of degree I have. It’s not that I’m trying to hide it, and it’s definitely not intentional, but it’s one of those things that isn’t that easy to figure out. Until recently, many curators (even ones I’ve worked closely with) didn’t know how old I was. This is a little different now that someone recently went in and added this information on Wikipedia. So, yes, there is lot of information about me out there (which is the everything), but at the same time there is very little meaningful information that will have any significant value (which would be the nothing).