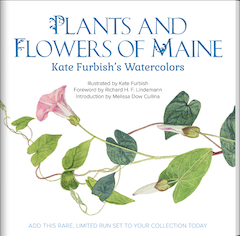

A Big Book of Wildflowers: Kate Furbish’s Botanical Drawings

By Rebecca Goldfine

Stefko is the director of Bowdoin Library’s George J. Mitchell Department of Special Collections and Archives, which has protected Furbish’s body of botanical drawings and watercolors for more than 100 years. The library has recently partnered with Jed Lyons ’74, president and CEO of Rowman & Littlefield, to publish, for the first-time, a complete two-volume edition of Furbish’s illustrations of Maine’s flowering plants and conifers.

The new green-bound books are massive, together containing more than 1,300 pages. Each page is devoted to a full-size, full-color reproduction of a Furbish painting. “What mattered most to us was the quality of images, and also that this be a book of scholarship, that it would show the artistry but also the quality of Kate Furbish’s thinking,” Associate Librarian Judy Montgomery said.

Richard Lindemann, the director of the Bowdoin Library archives for 15 years, wrote the book’s foreword.

Furbish was born in 1834 and died in 1931; her most productive years were between 1870 and 1908. She spent much of these decades traveling by stagecoach, rail, boat, and on foot to all corners of Maine to document and collect specimens of the state’s plants and mushrooms. She assiduously observed specimens in nature and ones she brought home, creating thousands of intricate, accurate, and beautiful drawings. Though she had no formal education as a scientist, she attended art school in Portland, Maine, and also in Europe, and she traveled regularly to Boston for botanical lectures. Her father, a successful hardware store owner in Brunswick, taught her how to identify local plants when she was a child.

Called ‘crazy,’ a ‘fool’ — and this is the way that my work has been done, the flowers being my only society, and the manuals the only literature for months together. Happy, happy hours!”

“Like Audubon, Kate Furbish worked on a real-life scale to represent the plants as accurately as possible,” Stefko said. Furbish began her illustrations by making detailed pencil renderings, which she then filled in with watercolors. Her depictions were sometimes composites of several samples to show the plant at different stages of its life. “This would be the most useful information for people trying to identify plants,” Stefko explained.

Abiding by scientific practices of the day, Furbish would record the plant’s Latin name, where and when she found the specimen, and often include small sketches of the plant’s seedpod, pistil, and stamen.

Funding for the project came in part from Coastal Maine Botanical Gardens and the Philip D. Crockett ’20 endowed fund, which supports the preservation of special collections at Bowdoin.

Furbish is perhaps most famous for discovering a new species of plant in Maine, a lousewort, which ended up playing an important environmental role a century later. In 1880, when she was in Aroostook County, Furbish came upon some plants with yellow leaves growing by the Saint John River. These plants—which were later named after her, Pedicularis furbishiae—are found only along a 130-mile stretch of this river. In the 1970s, a huge hydroelectric project proposed for the Saint John River was scrapped when enough concern was raised that the dam would imperil the lousewort’s habitat.

“I imagine her as a force of nature.” Stefko said of Furbish. “She was described as a very small woman, fiery, determined. Nothing escaped her view or attention.” At this, Stefko pointed to a tintype of Furbish as a young woman in which her eyes appear light, clear, and penetrating.

In 1908, when she was 74 and debilitated by neuralgia, Furbish donated to Bowdoin 14 volumes of her catalogs, containing 1,326 plant illustrations. She also gave two volumes filled with 500 mushroom drawings. “She felt the collection needed to stay in Maine, and that this would be a place where students could use it and appreciate it,” Stefko said. At the time, there was no other comprehensive guide to identifying plants—certainly none with such exquisite drawings. “These would have been very helpful for beginning botanists, and maybe to faculty,” Stefko said.

Bowdoin President William DeWitt Hyde appeared to be grateful for Furbish’s donation, and had a special cabinet made to hold her illustrations. Furbish thanked Hyde in a note (which is also preserved in the library archives). “I have laid all but one of my children to rest on its velvet couches,” she wrote. In another document, she professed, “I hope [the collection] will assist the earnest student instead of serving merely to entertain the visitor. If this proves true, love’s labor is not lost.”

Stefko offered an update to Furbish’s wish. “Now her labor can be found anew,” she said.