Russia On The Rise? Prof. Laura Henry Asks 'Is Putin's Bravado a Sign of Strength or Weakness?'

By Tom Porter

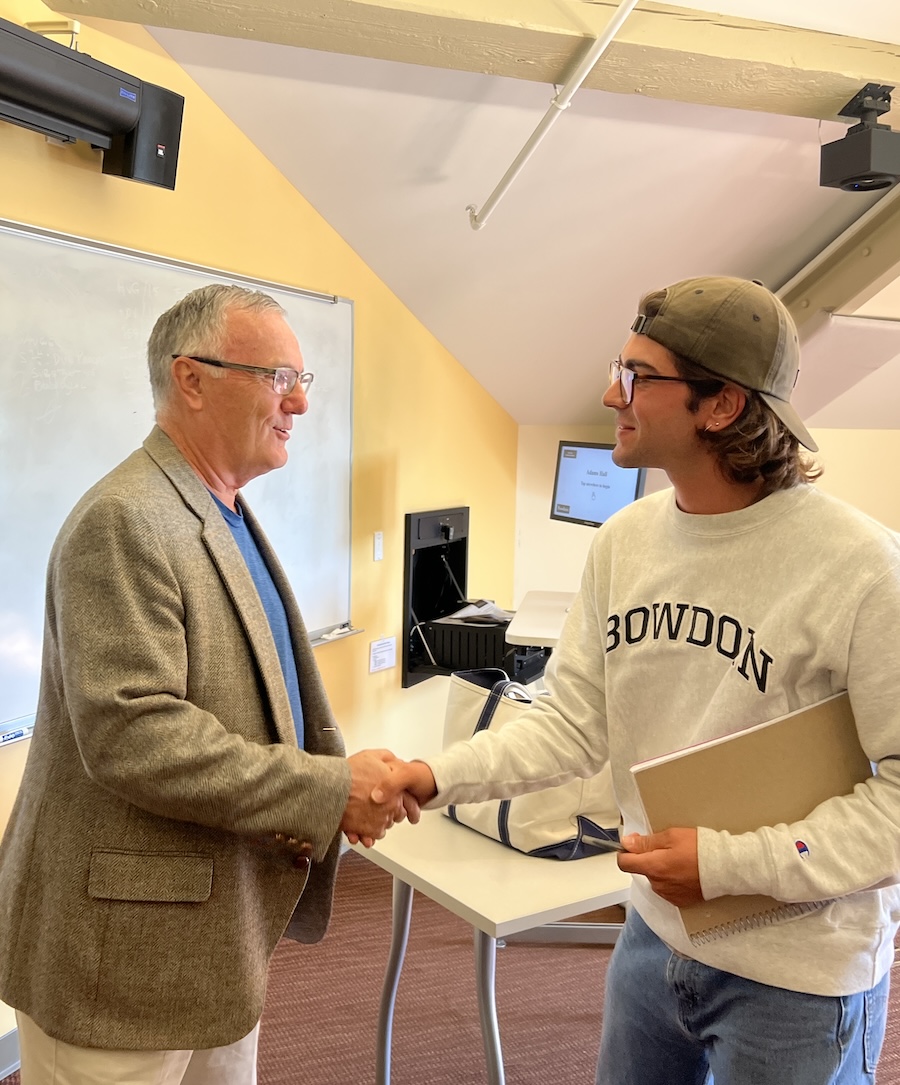

In the four years since he returned to the Kremlin, Russian leader Vladimir Putin has presided over an aggressive foreign policy that has seen the annexation of Crimea as well as military interventions in Ukraine and Syria. Putin may be acting like a strong man on the world stage, but how strong is the Russian president’s position domestically? This was a question posed by professor Laura Henry at a lecture delivered April 5. Henry is the John F. and Dorothy H. Magee Associate Professor of Government, and Acting Chair of the Russian Department.

Henry was interviewed by Bowdoin College writer and multimedia producer Tom Porter April 8. She was a guest on the program ‘Bowdoin and Beyond,’ which airs Fridays 3 p.m.-4 p.m. on WBOR radio.

Edited excerpts from the interview:

Tom Porter: Your lecture was called Russia on the Rise? Why the question mark?

Laura Henry: Because that is the real question being asked by all Russia-watchers these days. We’re asking ourselves “is this a newly resurgent Russia? Are we seeing a return to the cold war? Do we need to worry about a regime willing to use military force to achieve its goals? Or is Russia a fundamentally weak regime and its foreign policy an expression of that weakness?”

TP: I understand you discussed the fallout in Moscow from the recent release of the so-called “Panama Papers,” which document how many public officials and wealthy individuals hid their assets from public scrutiny. What’s the Kremlin’s view on this story?

LH: The interesting thing here is that Putin doesn’t appear in the Panama Papers. So the Russia media is characterizing international press coverage of this issue as ‘Putin-ophobia’ for the way its portraying their leader. Putin’s name is being discussed however because one of his close friends, a professional musician named Sergei Roldugin, is revealed to be worth $2 billion, an inconceivable sum for a talented but modest cellist living in St. Petersburg. Many people think this is evidence that while Putin does not control wealth directly, he has many close friends and colleagues who control wealth on his behalf. These people are called “white gloves” who stand in for political officials and control the money. It’s also important to consider that Panama is not the most important state in terms of Russia’s corruption – we think more of Cyprus or Switzerland as being a haven for Russian money – so the fact that there’s $2 billion there that can be indirectly linked to Putin seems evidence of the vast sum of money that he does control.

TP: How much is Putin’s position affected by factors such as oil prices and sanctions?

LH: Those are central factors. The legitimacy of Putin’s first two terms in office, from 1999 to 2008, was founded on rising living standards fueled by rising oil prices. So Russians were happy to create a new social contract with Putin whereby in effect they would exchange improved infrastructure and higher living standards for a kind of political acquiescence to an increasingly authoritarian and semi-corrupt regime. But now, since 2012, Putin’s back in office and this legitimation strategy no longer works. We’ve not only seen the collapse of oil prices from $110 a barrel to as low as $18, but we’ve also seen the effect of economic sanctions on Russia. We’ve seen the currency slide in value from about 25 rubles to the dollar up as high as 80, and this is problematic for the many Russians who took out mortgages, car loans or other loans denominated either in dollars or euros. So their income has shrunk but their obligation or debt remains the same.

TP: So what effect is all this having on Putin’s popularity within Russia?

LH: It’s fascinating to note that Putin’s popularity rating has remained at about the 80% mark, which would be the envy of any western politician. So how does he do it? Well it helps if you look at how Putin’s domestic and foreign policies have become intertwined. The 2004 “Orange Revolution” in neighboring Ukraine was an important moment for Putin and his regime when they looked next door and saw a huge social movement led by youth emerge in response to voter fraud in a presidential election. And that brought politics to a halt, forced a rerun of the election, and removed a corrupt and semi-authoritarian leader in favor of a more pro-western president.

So that was the moment when Putin began an interesting dual strategy: one of eliminating the power of his own civil society domestically, and two, of opposing all so-called democratic revolutions and humanitarian interventions abroad. What we see now in the last three years or so, is Putin using his foreign policy to legitimate his position at home. He can no longer rely on the social contract and rising living standards, but he can get people to rally round the flag in a patriotic way to defend ethnic Russians in Ukraine or Crimea. He also aims to prevent the West from meddling in a regime and destabilizing it, as they have done in Syria, Iraq and Afghanistan, according to Putin’s view of the world. Putin has also been quite successful in capitalizing on the war against Islamic extremists in the Middle East, where he hopes to build a new coalition with the West. Putin sees Russia’s role as a great power that the West needs when it comes to fighting Islamic terrorism, all of which has helped him maintain a high popularity level at home.

TP: Does Putin have any genuine political foes in Russia?

LH: Vladimir Putin has very effectively made sure there aren’t many alternatives to his rule in Russia. He’s done this by limiting NGOs and opposition parties, and also by domesticating opposition parties like the communists and nationalists who work very closely with the Kremlin now. So many Russians, even if they don’t like him, believe that their choices now are Putin – preferably in charge of a strong state – or chaos and instability. And that’s the message they get from the nightly news. In that media environment – when you control television and much of the press – you can make a strong case that “we need to protect vulnerable populations abroad, against the threat of regime overthrow and instability.” That’s what Russians believed was happening in Ukraine, that’s what they believe is happening in Syria.

TP: So does Russia remain on the rise?

LH: It’s interesting because there is definitely this image of Russia being on the rise, but I think when you actually peel back the onion and ask “Is this a strong and durable regime? Are these the actions of a strong leader?”, you can see that the regime is quite fragile in many different ways. As we’ve discussed, because of economic challenges at home, Putin is having to use foreign policy as a legitimation strategy: that smacks of desperation and is actually quite risky. A military defeat, even a confrontation (think about the downing of a Russian jet by the Turkish military a few months ago) could be very bad for Russia indeed. So I think in some ways this is a strategy that’s meant to buy some time for the domestic economy to recover. It’s not a very stable way to build a regime in the long-term.

TP: What might Russia look like if Putin were to fall from power?

LH: While some of Putin’s critics might welcome the idea that his regime is more fragile than it seems, unfortunately the political forces that would follow Putin are likely to be even worse, from an American point of view. For example, Putin is the guarantor of stability between Russia’s political and economic “clans.” In his absence, we could see a kind of civil war among the elite. In recent years, we also have seen rising nationalist sentiment in Russia, providing space for a right-wing coup against Putin and a regime that would likely be more opposed to the West.

TP: What does all this mean for US foreign policy?

LH: The important thing about US foreign policy is not to get too hysterical about Russia. I think this rhetoric of “Russia is our greatest enemy,” and “a return to the cold war,” is really quite overblown. I think Russia is in many ways a normal power pursuing its self-interest, albeit in a somewhat aggressive, erratic and opportunistic way. So I think it’s kind of important that we draw clear limits with Russia in terms of ways in which we are willing to engage, and in which we’re not willing to engage. I do think it’s important that we don’t leave Ukraine high and dry, that we don’t get completely distracted. But at the same time we do have to be realistic about our policy towards Russia.

Moscow is going to insist upon a sphere of influence, it’s going to keep taking measures to make sure it has that sphere of influence, and I think we need, at least in the short-term, to acknowledge that. I don’t believe Russia will invade the Baltic states – I don’t think Estonia, Lithuania and Latvia are vulnerable. I know a lot of people talked about that after the conflict in eastern Ukraine broke out. And I do think it was wise of NATO to rotate troops and military in the Baltic region, just to raise the cost of any possible action, because I don’t think Vladimir Putin is irrational, I don’t think he wants to pay a huge cost. I think he realizes that for the most part Ukraine is not of strategic interest to the West and he could probably get away with what he’s done so far. But I think we can’t lose interest in the region, we have to stay engaged.

Listen to the full interview (audio may take a few seconds to load):