From Dante to Battlestar Galactica: Analyzing 'World' Science Fiction

By Tom Porter

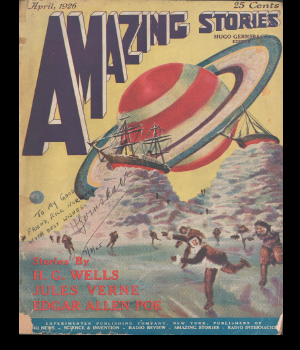

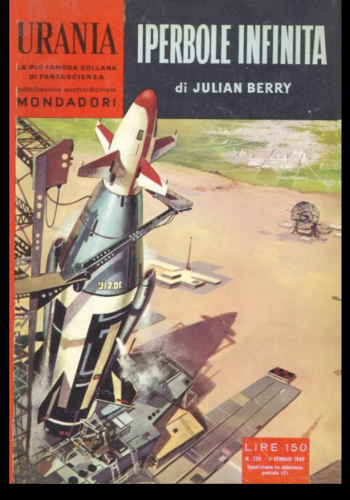

As an academic Arielle Saiber cut her teeth on Italian literature of the medieval and renaissance period. She’s a renowned Dante scholar and vice-president of the Dante Society of America (founded at Harvard by Bowdoin’s own Longfellow in 1881), and also writes about medieval and Renaissance mathematics and physics. But Saiber, associate professor of Romance languages and literature, is also a devotee of science fiction: She’s published on the subject, recently taught a course on “World Science Fiction,” and is editing the first-ever anthology in English of Italian science fiction for Wesleyan University Press.

On April 6, as part of the Faculty Seminar lecture series, she delivered a lunchtime talk to the Bowdoin community called “So Say We All: The Fiction of World Science Fiction.” The lecture, said Saiber, takes its title quote from the American science fiction franchise Battlestar Galactica, but if there’s one thing she was keen to stress, it’s that science fiction (SF) is a global movement that goes far beyond the well-known texts and films of the English-speaking world. Indeed, Saiber argued, it seems unjust to differentiate between Anglophone SF and other so-called “world” science fiction: “The concept of ‘world’ science fiction,” she explains, “is itself a fiction; that is, we shouldn’t be talking about ‘world’ SF, we should just be talking about SF. Wherever there is scientific practice and literature, dissatisfaction with some aspect or multiple aspects of society/the world, and concern for the future, you will find SF.”

While Saiber’s fascination with science fiction began with Anglophone SF when she was a teenager, her current focus is Italian SF, which she says is not unrelated to her work as a scholar of Dante and premodern science: “I see clear links between elements of medieval thought and science fiction. Take Dante’s Divine Comedy, for example: Dante imagines a journey to three other realms – Inferno, Purgatorio, and Paradiso – one of which (Paradiso) is completely other-worldly, filled with planets, stars, cosmic paradoxes, and hard-to-comprehend ‘alien’ entities, such as angels, the blessed, and a mysterious point of light from which all heaven emanates.”

Yet calling the Comedy a work of SF or proto-SF is somewhat problematic within the world of SF studies. Saiber said: “Science fiction has been described as many things, from the literature of ‘what if,’ to simply ‘anything published as science fiction.’ The British writer Arthur C. Clarke, who among many great works, wrote 2001: A Space Odyssey and collaborated with Stanley Kubrick on his 1968 film of the same name, said ‘Science fiction is something that could happen – but you usually wouldn’t want it to. Where fantasy is something that couldn’t happen – though you often wish that it could.’ It is all of those things (and much more); it is also a global, globalized, and globalizing genre.”

Saiber noted that while there has long been a bias against the genre in the academic world, this is changing: “More and more universities are offering SF courses. Besides being a way to engage in scientific thought experiments, much SF is deeply committed to exploring philosophical questions, politics, ethics, the environment, religion, gender and sexuality, and just about any critical issue there is.” As with any genre, said Saiber, there is a range in quality, “but in good science fiction, whether it’s written, or produced as a movie or TV series, the questions asked are often urgently related to our times, such as ‘what does it mean to be human? What are our responsibilities to society, to this planet, and to the universe beyond?’”

Saiber believes that good science fiction is anything but a “light” read: “It can be wildly complex, intensely unsettling, and even spark major shifts in scientific imagination. In some ways, it scares us because it shows what reality might actually be or become.” And this, she said, is why SF is so important to read, write, and discuss. “It offers us a way to look at current realities through speculating on what might be underneath what we see and think we know, and on what may be coming our way given how we live now.”