Why Are America's Schools Re-segregating?

By Tom Porter

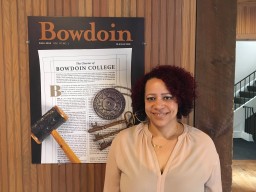

Journalist Nikole Hannah-Jones has received national recognition for her investigative work into racial injustice in the US. She was named Journalist of the Year by the National Association of Black Journalists and her reporting has won numerous awards. Hannah-Jones, currently a staff writer with the New York Times Magazine, was on campus March 28, 2016, to deliver the Santagata lecture “About Apostrophes: The Devastating Consequences of America’s Resegregating Schools.”

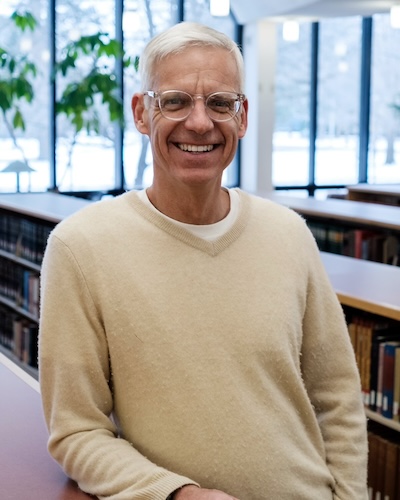

She spoke with College Writer and Multimedia Producer Tom Porter

Listen to the interview (audio may take a few seconds to load):

Tom Porter: Your talk was called “About Apostrophes: The Devastating Consequences of America’s Resegregating Schools.” Why?

Nikole Hannah-Jones: I called it “About Apostrophes” because I started my speech talking about a young lady I met a couple of years ago called D’Leisha and she had an apostrophe in her name. Apostrophes are often seen as a signifier of black American naming practices and what the research shows is that anyone from teachers to people who are hiring for positions, to elected officials, when they see black-sounding or black-looking names, they tend to discriminate against those children. So I was using that as a way to get into a story about black low-income children who are being segregated in schools, and whether we think kids like that deserve the same education and opportunities as other kids.

TP: How have America’s schools become re-segregated?

NHJ: Following Brown v Board of Education and some subsequent Supreme Court rulings, we had a pretty rapid period of de-segregation, particularly in the South. But it came because of court orders and starting in the 1980s you began to see court orders being lifted, and as communities were no longer forced to integrate, they’ve started to do things that re-segregate students.

Outside of the South we’ve never seen any real effort to integrate schools and so in places like Chicago, New York City, Boston, Newark, where you saw white parents pulling out of the public school system and moving to the suburbs, this has led to increasing segregation in those cities as well.

TP: So it’s really indicative of the socio-economic separation that black communities suffer?

NHJ: Well, it’s both and I think that it’s not just class, because what we know is there are large numbers of poor white students and those poor white students are not being segregated in schools. Poor white students are actually tending to live in middle class neighborhoods and going to middle class schools. So it really is a segregation by both race and class. And what the data also show is that middle class black parents and families are still living in segregated poor neighborhoods, and often are still having to send their kids to segregated poor schools.

TP: And that largely is because better off, white communities, are not wanting to be part of that district?

NHJ: Yeah, I think there’s still a great deal of discrimination that’s occurring and what we know from testing done by different agencies is that there’s still a lot of housing discrimination going on and there are still a lot of efforts being made to keep poor black children in separate schools.

TP: You talk about the devastating consequences of this. What effect is it having?

NHJ: Well the consequences are the same as they’ve been before Brown v Board of Education, is that black students separated in their own schools do not get the same quality of education, they don’t get the same quality of teachers, they don’t get the same quality of instruction, they don’t get the same facilities. But even more important than that, when we keep black kids in segregated schools, they go on to live segregated lives and it’s actually harmful long-term for them.

TP: Are there any models for success out there? Any glimmers of hope for re-integration?

NHJ: Yeah I mean there are different places that have never given up and have been working very hard to re-integrate students. Most of them are in the South. One place considered a national model is Wake County in North Carolina. They’ve had a voluntary integration program for a couple of decades, it’s been very successful. Another place people point to up north is Hartford, CT, which was ordered by the state court to integrate its schools and it has a magnet program that draws in white kids from the suburbs to integrate the schools. So there are places that have tried, it’s just that most places aren’t trying very hard.

TP: America finds it hard to address issues of race, you say. Why is this?

NHJ: I think because racism is the invisible factor that surrounds everything in this country. It is the foundation of who we are. Race is written into our constitution, race was written into our declaration of independence, our founding fathers were slave owners so I think racism in this country is probably as American as apple pie.

TP: So while many may deny being racists, they’re still motivated unconsciously by racism?

NHJ: Yeah I think what happens is you had entire systems set up around discrimination and we haven’t destroyed those systems. So it’s not even necessarily about one person who has racial animus against another person, it’s about entire systems that operate on their own whether we choose to be racists or not. For instance an example of that would be public schools. If public schools were forcibly segregated 20 years ago, 30 years ago, 40 years ago, and we haven’t done anything to undo that segregation, that segregation just keeps going on its own.