Bowdoin to Celebrate 400 Years of Shakespeare

By Rebecca Goldfine

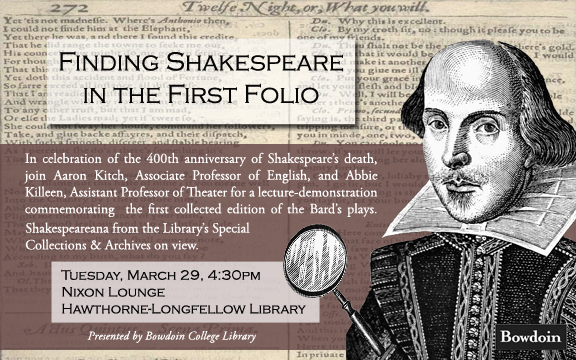

To honor the 400th anniversary of Shakespeare’s death in 1616, two professors from Bowdoin’s theater and English departments will present on the First Folio, the first published collection of Shakespeare’s plays.

Almost 400 years after the First Folio was published, this collection of 36 plays remains the topic of much scholarly debate. Associate Professor of English Aaron Kitch and Assistant Professor of Theater Abbie Killeen will give a lecture and workshop at Bowdoin on March 29, at 4:30 p.m. The event will be held in the Nixon Lounge of the Hawthorne-Longfellow Library.

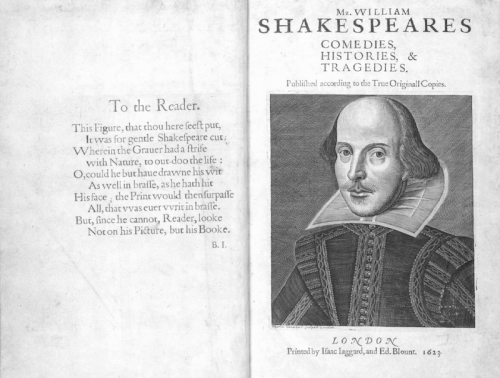

The event coincides with a national tour of the First Folio, one of the most valuable printed books in the world. About 300 original copies were made in 1623, seven years after Shakespeare’s death, and 233 copies remain. This spring, from March 4 to April 2, a First Folio will be on display at the Portland Public Library. The Portland library is also organizing a number of lectures, performances and other events around the exhibit, including a talk by Kitch, “Finding Shakespeare in the First Folio,” on March 31.

Kitch said he will address the First Folio in relation to early modern print culture and its connotations for the idea of authorship. He explained that most scholars believe that Shakespeare did not want his plays published, most likely because the playwright could earn more money from ticket sales to his plays than from sales of published scripts. Yet, some of Shakespeare’s plays did appear in published form during his lifetime, in smaller volumes called quartos.

In 1623, two actors from Shakespeare’s playing company undertook the costly endeavor of publishing a collection of 36 of Shakespeare’s plays, though it remains unclear what texts the publisher used to create the folio. A few plays, including Macbeth and Twelfth Night, had never been published before. “Did they use a script from the playhouse, or the author’s papers that some call ‘foul papers,’ or some combination of these?” Kitch said. “Was there any editing involved? How do we understand the process of production, with multiple textual sources and compositors of varying skill levels who actually did the printing?”

In addition, each later folio edition of Shakespeare’s plays differs from the others. “It was not until the 18th century that people began to ask, ‘What did Shakespeare write and how do we know?’” Kitch added.

With Killeen, Kitch will also explore the relationship between the theater and the book, and the way print culture and theater culture intersected. “You have to think about the authority in the playhouse in relation to the authority of the printing house,” Kitch said. Theaters can take liberty with plays. Shakespeare himself was known to scribble revisions on his scripts. “The question is, how does the First Folio give us access to Shakespeare and fail to give us access to Shakespeare at the same time?” Kitch asked.

Killeen will lead a workshop on some of the clues the text in the First Folio provides actors, and demonstrate how actors can move the story from the page to the stage, Kitch said.