At 10 Years: Doherty Marine Biology Program Launches Science Careers

By Rebecca Goldfine

This year, the Doherty Marine Biology Scholar Program at Bowdoin’s Coastal Studies Center is 10 years old. In the past decade, the program has supported four researchers who have launched successful careers from here while also inspiring many Bowdoin students to pursue similar scientific paths.

The Doherty program plays a large role in making the Coastal Studies Center on Orr’s Island an active research site. Funded by the Henry L. and Grace Doherty Charitable Foundation, the program was established in 2005 to “build and strengthen” Bowdoin’s marine and coastal science offerings. Doherty scholars are expected to do their own research, teach one marine biology course a year, and mentor students doing research projects. They are also asked to make connections with other Maine institutions engaged in marine science work.

The Doherty program plays a large role in making the Coastal Studies Center on Orr’s Island an active research site. Funded by the Henry L. and Grace Doherty Charitable Foundation, the program was established in 2005 to “build and strengthen” Bowdoin’s marine and coastal science offerings. Doherty scholars are expected to do their own research, teach one marine biology course a year, and mentor students doing research projects. They are also asked to make connections with other Maine institutions engaged in marine science work.

Bowdoin’s four Doherty scholars — Jonathan Allen (2005-2008), Daniel Thornhill (2008-2010), Trevor Rivers (2011-2012) and current fellow Sarah Kingston — have pursued very different research directions at Bowdoin, although all have taken advantage of the Coastal Studies Center’s location on the Maine coast.

Jon Allen, an associate professor of marine biology at the College of William and Mary, works on the life histories of creatures familiar to most of us who live by the sea — marine invertebrates such as snails, sea stars, sand dollars and sea urchins. Dan Thornhill studies coral reef biology and deep-sea organisms. He is now a program director at the National Science Foundation in Washington, D.C. Trevor Rivers researches bioluminescence, and is currently a lecturer at the University of Kansas. Sarah Kingston is looking into possible genetic variations in marine organisms that may influence their response to stresses like ocean acidification and climate change.

All four scientists say they were drawn to the Doherty program by the chance to work at a liberal arts college. Generally, post-doctorate options for young researchers tend to be in labs at larger research universities. “There are very few opportunities to be a post-doc at a place like Bowdoin,” Allen said. “And I was looking to go back to a liberal arts world.” Allen got his B.S. from Bates College, in Lewiston, Maine. At the end of his three years at Bowdoin, when he was seeking a tenure-track job, Allen said he felt he had an advantage at liberal arts colleges. “The experience helped me stand out among other candidates at places where teaching is valued,” he noted.

Another benefit to working at the Coastal Studies Center was the independence he was given, he added. “I had the freedom to do what I wanted, with access to the marine lab and to undergraduates who could do research with me in the summer,” Allen remarked. “I was able to be successful being independent, and that helped me stand out on the job market, too.”

When Allen was at Bowdoin, he designed and taught two courses, Evolution in America and Marine Larval Ecology. He also co-published a paper with a student, Nicholas Alcorn ’08, as well as published several other papers. In addition, he organized two symposia at Bowdoin on the state of marine ecology in Maine. Allen maintains his ties to the Coastal Studies Center, returning each summer with a team of undergraduates to continue his National Science Foundation-funded research of intertidal invertebrates. You can read about his work here.

Thornhill said he quickly “grew to love Bowdoin.” He praised the caliber of students in his two semester-long classes, Coral Reef Biology and Evolution, and in his spring break course on coastal ecology in south Florida. Among the papers he published based on his research at Bowdoin include a couple of papers with Bowdoin undergraduates as co-authors. Three of the students he mentored are now in graduate school for marine biology or have their PhDs, he said.

While he was at Bowdoin, Thornhill continued his research into corals’ adaptivity to changing ocean conditions (while he mainly studies tropical corals, there is a coral species that lives in Maine waters). He also studied deep-sea worms that thrive on the sea floor despite not having digestive systems, living instead off of symbiotic bacteria that convert into sugar the energy from a toxic chemical found naturally throughout the deep sea, especially at hydrothermal vents and methane seeps. Thornhill recently returned to Bowdoin to give a workshop to faculty on how best to apply for NSF grants, and to participate in the Teach-in on climate change and social justice.

During his time at Bowdoin, Rivers taught two course, Visual Ecology of Marine Animals and Senses in the Ocean, and mentored several undergraduates who worked with him in the marine lab. Four are continuing their studies in marine science post-Bowdoin. Rivers also hosted a marine ecology symposium in 2012.

Echoing Allen and Thornhill, Rivers said the most valuable part of the Doherty program was having so much independence early in his career. “It is a time when you can put up with a little bit of risk and pursue risky questions,” he said. Rivers is continuing much of the research he began at Bowdoin. “It let me lay down the groundwork for projects and grant proposals down the line. I used it as a mining time.”

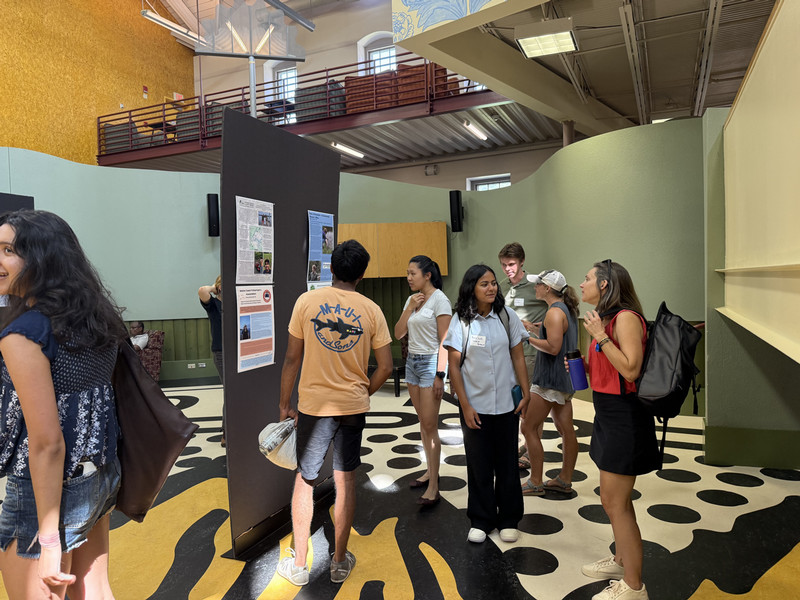

In the big picture, Kingston’s evolutionary biology research focuses on understanding how marine organisms’ genetics might influence their adaptations to climate change and ocean acidification. At the moment, she is looking at how genetic variations in blue mussels correlate with their ability to cope in stressful environments. Read more about her research and her student assistants.

Kingston said she finds “something special” about working with undergraduate students. “The undergraduates here at Bowdoin have blown me away with the amount they can do and how eager they are to learn,” she said. “It’s a special opportunity for me to show students a world that grabbed me at their age.”