Kent Island Life: Investigating the Decline of Herring Gulls

By Emily Weyrauch '17

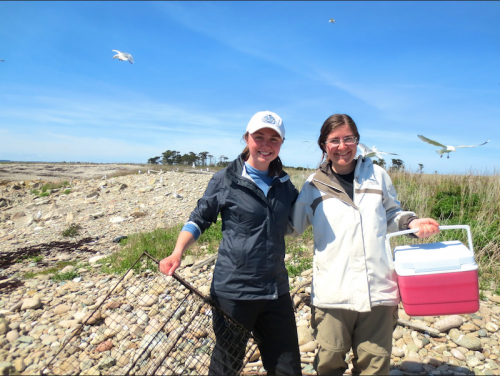

Getting dive-bombed by herring gulls on a remote island is not how many students choose to spend their summers, but for Claire Schollaert ’16, it comes with the territory.

Schollaert is spending her summer at the Bowdoin Scientific Station on Kent Island in New Brunswick, Canada, conducting field research on herring gulls and their foraging habits.

Schollaert, a double major in biology and anthropology, is working with University of New Brunswick Master’s candidate Kate Shlepr. Shlepr is stationed on Kent Island for a week before returning to her research site on Brier Island, Nova Scotia. The herring gull colonies on Kent Island and Brier Island are the two largest colonies in the Bay of Fundy region.

In her time on Kent Island, Shlepr is setting up gull research, which Schollaert will continue throughout the summer.

According to Damon Gannon, director of the Bowdoin Scientific Station, herring gull populations have been in steady decline since the 1980s. The decline coincides with the decline of fisheries, the closure of open-pit landfills, and with changes to the ocean ecosystem. “Characterizing the source of their diet will help shed light on what’s actually causing these declines,” said Gannon.

Shlepr’s project investigates herring gull foraging behavior in the lower Bay of Fundy. Since she arrived on Kent Island on May 31, she and Schollaert have been working full days, beginning at 7:30 a.m. and ending at 6 p.m. or later. “I really like that it’s so hands-on. It’s a really dynamic way of working,” said Schollaert.

After an initial survey of the herring gull colony, Schollaert and Shelpr identified nests to include in their research, and then began trapping the gulls to collect samples and attach GPS tags.

This process involves placing a netted trap over a nest, replacing the gull eggs with fake eggs to prevent damage, then waiting for an adult to come back to incubate the eggs, which triggers the trap. Once they trap a gull, Schollaert and Shlepr take body measurements, collect blood samples, band the bird, and attach a GPS tag that tracks the gull’s movements. Each day, the duo tags 10-12 birds. This setup will allow them to track the foraging patterns of the gulls that nest on Kent Island and test how this correlates with the food that they eat.

Schollaert describes the research as “a lot nicer than being in a lab.” However, she notes that the gulls “can be pretty aggressive around peak breeding time as the chicks get closer to hatching.”

After Shlepr leaves Kent Island, Schollaert will continue taking data for Shlepr’s project, checking on the eggs from the tracked nests, then monitoring chick growth rate and fledging success, and eventually banding the birds when they are big enough.

In addition, Schollaert plans to expand on Shelpr’s research. During the rest of the summer, Schollaert will be analyzing the variation between siblings in a brood of herring gulls, using measures of growth rate and survivorship in conjunction with Shelpr’s research on food foraging to examine possible correlations.

Schollaert and Shlepr are not the first to study the island’s herring gull population. According to Gannon, herring gull research by Bowdoin scientists on Kent Island goes back to 1934, before it became an official research station.

“I’ve heard a lot about research that has come out of this place since I started studying birds as an undergrad, I’ve heard a lot of the big names like Nat Wheelwright, Alfred Gross —so it’s exciting to be here,” said Shlepr. “It’s beautiful, the infrastructure is very well put together for research, which is nice, and the island is gorgeous.”

Schollaert and Shlepr have what a scientist might call a symbiotic relationship, one that is beneficial for both parties.

“I wanted to pick something that would fit nicely within Kate’s project — to keep the amount of nests I’m monitoring manageable and to be able to use the data she’s collecting for my work,” said Schollaert. “I also want to contribute what I can to her study.”

Using the research from this summer, Schollaert hopes to pursue an independent study or honors project in biology during her senior year. Her interest in seabird field research was first piqued last summer when she worked for the National Audubon Society’s Project Puffin.

After Bowdoin, Schollaert wants to attend graduate school and continue doing research. “It’s really cool to see what that next step after undergrad looks like, to be a part of [Shlepr’s] research, and learn about her experiences,” she said.

And getting dive-bombed by territorial gulls? “It doesn’t hurt that bad. It’s just kind of shocking,” Schollaert admitted. “And the poop’s not so bad. You get used to it.”